Open government is a cornerstone of an open society–a society where voices can be heard, ideas debated, and where there is opportunity for exchange between government and its people. That governments should be transparent, participatory, and accountable to the public is not a new idea. It dates back many decades, even centuries in some places. The last several decades have seen an accelerated spread of open government and its associated concepts well beyond traditional advocates.

The founding of the Open Government Partnership (OGP) in 2011 has been key to this growth. Initially established by eight governments and a number of recognized civil society organizations, the new partnership reflected a time of optimism about the power of democracy, technology, and open government to change lives. Together, this core set of countries pledged to work to spread more open societies.

Despite these encouraging trends, recent years have witnessed a recession in openness and democracy. This has been most acute in countries once viewed as champions of democratic transition. It has also taken place in some of the world’s largest democracies. Some governments, which had been considered to be candidates for transition, have instead strengthened and exported authoritarian practice.

The time is right for an honest assessment of these trends. The Partnership provides a critical resource of lessons for shaping future reforms: what has worked, what hasn’t, and what lies ahead. Today, having grown to 99 members, OGP has been a laboratory for experimentation and reform, learning and accountability over the last ten years. Together with civil society, governments have collectively undertaken thousands of commitments worldwide through their two-year action plans, collaborated across sectors, and have been publicly evaluated on the success of their efforts. Perhaps just as importantly, the Partnership has created a global community of reformers working on the dozens of issues needed to advance open government. Moreover, it is a community to which countries seeking their own reforms can now turn to learn what they might adapt for their situations.

This report also lays out where the Partnership and its members could go over the course of the next decade. Its findings build on the tremendous knowledge and experience of civil society organizations who have used OGP action plans to advance their issues; government officials who have worked to implement difficult, often political reforms; and the international organizations that work to lift up reformers every day.

OGP at a GlanceOpen Government Partnership brings together government reformers and civil society leaders to create actions plans that make governments more inclusive, responsive, and accountable.To become an OGP member, countries must first endorse a high-level Open Government Declaration and commit to delivering a two-year action plan developed with public consultation, as well as independent reporting on their progress going forward. The Open Government Partnership formally launched on 20 September 2011 with eight founding governments: Brazil, Indonesia, Mexico, Norway, the Philippines, South Africa, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Since that time, 79 OGP participating countries and 20 subnational governments have made over 3,100 commitments to make governments more open and accountable. OGP is overseen by a Steering Committee, including representatives of governments and civil society organizations. |

The case for open government

Healthy democracies require competing ideas, not just elections

The current democratic recession is directly affecting the openness of societies. However, it is unique from past waves of authoritarianism. Today, there are considerably fewer extra-legal palace coups or military takeovers of governments than in the 1930s or 1960s, for example.1 Moreover, basic electoral systems have actually improved over the course of the past decade and suffrage has expanded.2

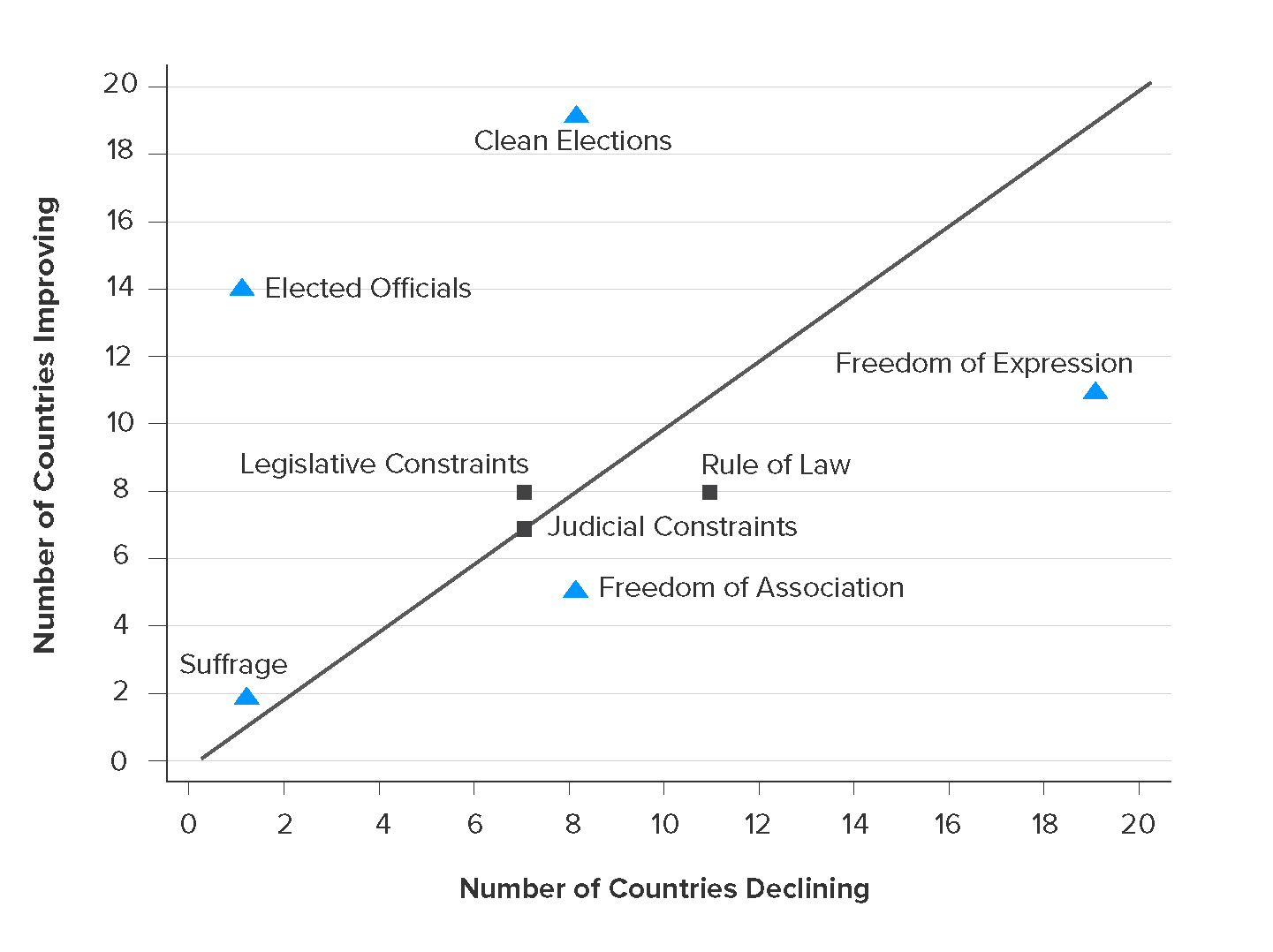

In contrast, it is the things that make elections meaningful–the civic life of countries–that has been eroded. Specifically, expert analysis show freedom of expression, rule of law, and freedom of association have declined in more countries than have seen gains. (Figure 1 below shows a net positive in the number of elements of improved free and fair elections, while fundamental freedoms continue to backslide according to the V-Dem Institute.)3 Cross-national public opinion polling from the World Justice project shows mixed results; with members of the public in 43 countries perceived improvements in freedom of expression, while 42 perceived declines.4

At the same time, some positive trends have emerged. For example, the democratic recession has not negatively affected all countries equally. Countries such as Kenya and Nigeria have made significant steps forward in strengthening democracy. Still others have simultaneously progressed in some areas while regressing in areas.

Even more encouraging, there is recent evidence to suggest the resurgence of political participation, specifically, participation by women and political minorities.5 Public opinion research by the World Justice Project shows that an overwhelming majority of the global population favors more open government (disclosures of the records of public officials, copies of public contracts, and detailed budget figures). These beliefs differ very little from country to country. Additionally, more people report engaging with media in 2018 than ever previously recorded.6

This places the Open Government Partnership in a critical position to build on the positive momentum and stop the attacks on open societies. The current wave of authoritarianism is taking place specifically outside of the electoral process and its solution will be found there, too.

Figure 1. Elections improve while fundamental freedoms backslide: 2007-2017 (Source: V-Dem Institute)

Source: V-Dem Institute, Version 8, April 2018

Open government works and open societies thrive

The evidence continues to show that open government makes a significant difference in people’s lives, especially as part of a broader ecosystem of accountability. Research increasingly shows that electoral democracy provides the most reliable long-term path to better health, longer life,7 and greater, more equitable economic growth.8 Less research, however, has specifically looked at democracy beyond the ballot box, especially the role of civil society and free media in promoting long-term inclusive growth. There are a growing number of arguments to support democracy beyond the ballot box.

First, there is a normative and legal case to be made for open government. Its aspirational principles serve as the foundation for democratic communities around the world. The right to freedom of expression, association, and assembly are clearly laid out in international human rights law, political agreements, and in the constitutions of nearly all countries. The rights to seek information, to participate in civic life, and to seek justice are similarly enshrined in international and domestic law.9 For many individuals and in many societies, these ideas may be adequate justification to pursue open government.

However, beyond these normative arguments, evidence continues to affirm the long-term, positive impact of open government and open societies. Modern societies and current social, economic, political, and environmental challenges are complex and cannot be solved by powerful actors or markets alone. An accountable, responsive, and capable government sets the framework in which individuals, communities, and markets can succeed. Core to this accountability is the free flow of information to and from government. This is possible only where there is free and independent media, unhindered civil society, and channels for people to exercise their rights.

The growing evidence is clear: where there is free and independent media, civil society organizations, and government engages with citizens, societies achieve better health, education, and economic outcomes. Supporting data exists at both a micro- and macro-level. What follows is recent research that looks at both micro-level impacts and the long-term effects of openness.

Micro-level evidence on impact

There is a growing body of case-study evidence that open government results in better outcomes across a variety of areas. These were summarized in the recent Skeptic’s Guide to Open Government, produced by OGP.10 Readers should refer to that document for extended case studies.

- Public service delivery: Public engagement in service delivery improved customer usage, service quality, and efficiency of spending in water (Korea), education (Kenya), health (Brazil), and infrastructure (Indonesia).

- Prevention of corruption: Lobbying reform in Chile and Estonia have led to greater public participation and access to elected and appointed officials, but also clearer information about influence. These efforts are part of a larger trend toward lowered corruption in each of these countries, and are considered models among their peers. Cote d’Ivoire has lowered perceptions of corruption in the country, in part through the establishment of local anti-racketeering committees, which include members of civil society.

- Efficiency of public contracts: Various studies have shown that open contracting can lead to cost-savings of between 7 and 25%.11 In Slovakia, moving to an open contracting system doubled the number of bidders, leading to increased competition.

- Trust: Research on trust and open government is still in its early phases. There have been studies which demonstrate that greater disclosure leads to an increased perception of honesty and benevolence on the part of government.12

Long-term impact of openness

There is a growing body of evidence on the impact of transparency, participation, accountability, and a thriving civil society and media.

Economic impact of openness

Despite limited long-term data, research on the relationship between economic growth and open government is considerably more developed than that of the other societal benefits. Generally, improved transparency is strongly correlated with better economic results:

- Economic growth and business environment: Greater policy transparency and frequent and accurate disclosure of macro-economic data is positively correlated with foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows and credit ratings.13

- Improved trade: An analysis of more than 100 trade agreements shows that each additional transparency clause enhances public visibility and predictability of applicable terms for all trading partners and is associated with a one percent higher flow in bilateral trade.14

- Reduced red tape: A study of 185 countries found that better disclosure of regulatory fee structures in four key areas (starting a business, obtaining construction permits, getting electricity, and registering property) is associated with higher quality regulations and reduced corruption.15

- Greater stability and reduced risk: Transparent publication of economic data leads to longer periods of political stability and democratic succession.16 Transparency in macro-economic data enables countries to borrow at lower costs, reducing credit spreads by 11% on average.17

- Expanded economic opportunity: In the European Union (EU), the total direct economic value of open data is expected to increase from a baseline of €52 billion in 2018 for the EU28 to €194 billion in 2030. Up to 75,000 jobs are estimated to have been created as a result of re-use of open data by 2016. This number is projected to grow to up to 100,000 by 2020.18 A study of G20 countries found that the average economic value-add of open data is US$2.6 trillion, and a committed move towards open data could help G20 countries realize half of their envisioned economic growth targets.19

Social impact of openness

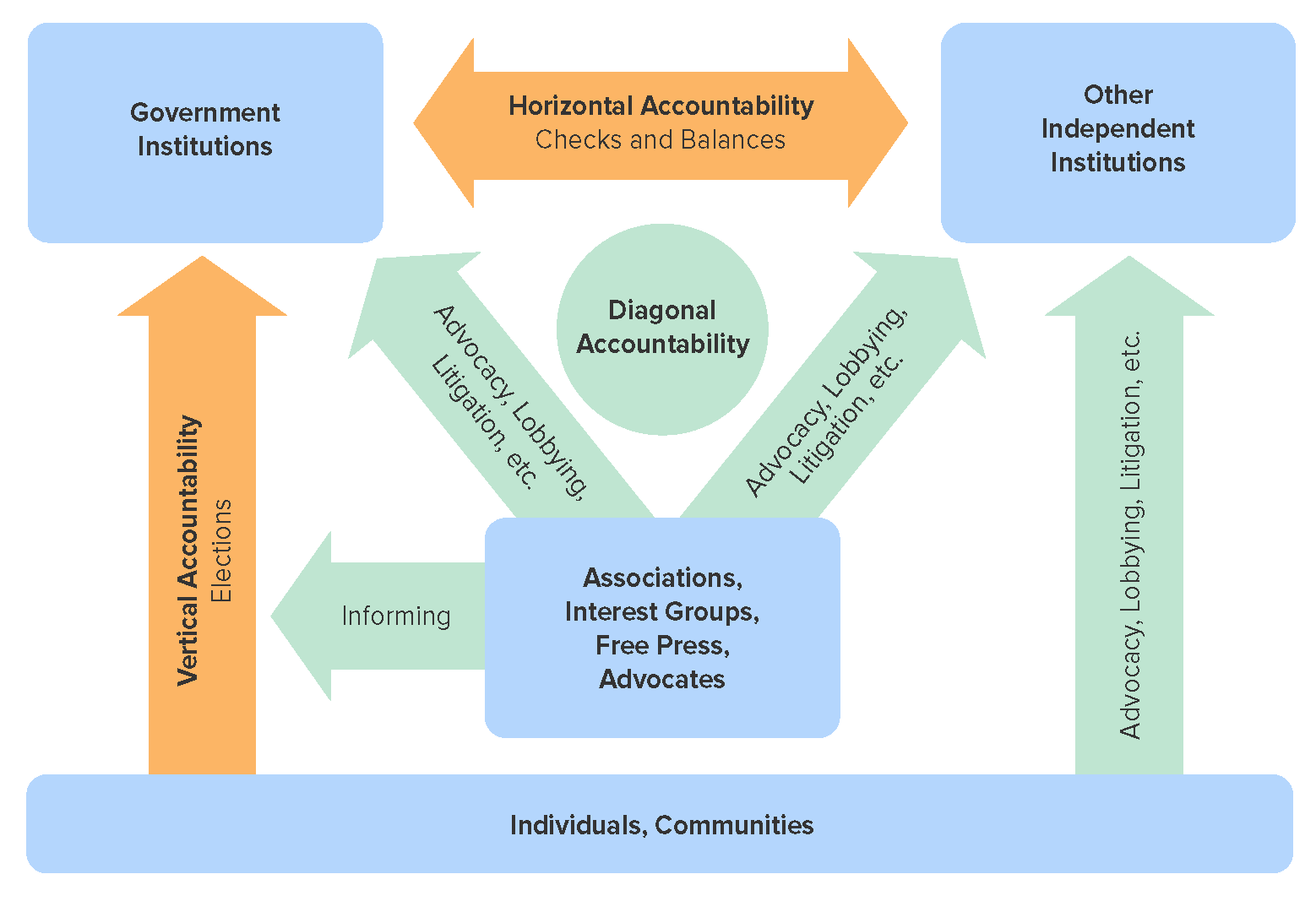

The social or human impact of more open societies is less well understood. To help mitigate the gaps in data, the authors of this report collaborated with the V-Dem (Varieties of Democracy) Institute, based at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden, who take an innovative approach to democracy analysis. Specifically, researchers looked at the long-term impact of freedom of association, free and independent media, and government engagement with citizens–referred to as “diagonal accountability,” and includes various health, education, and economic outcomes (See Figure 2: “Diagonal accountability” for the relationship between openness and other democratic institutions).

Until recently, determining the long-term effects of democracy (or openness) on development outcomes had not been possible. The Varieties of Democracy dataset has annual data on 170 countries which now allows for correlations to be run with other global indicator sets to identify what relationship, if any, may exist.

The results from this new look at openness data were clear–stronger civil society, free press, and improved channels for public engagement lead to better development outcomes. The researchers controlled to make sure that they did not confuse improved openness with other measures with which it is associated, such as national income, levels of urbanization, time lag, and interaction effects of stronger elections and checks and balances. Their findings tracked the effects across three categories:

1. Health

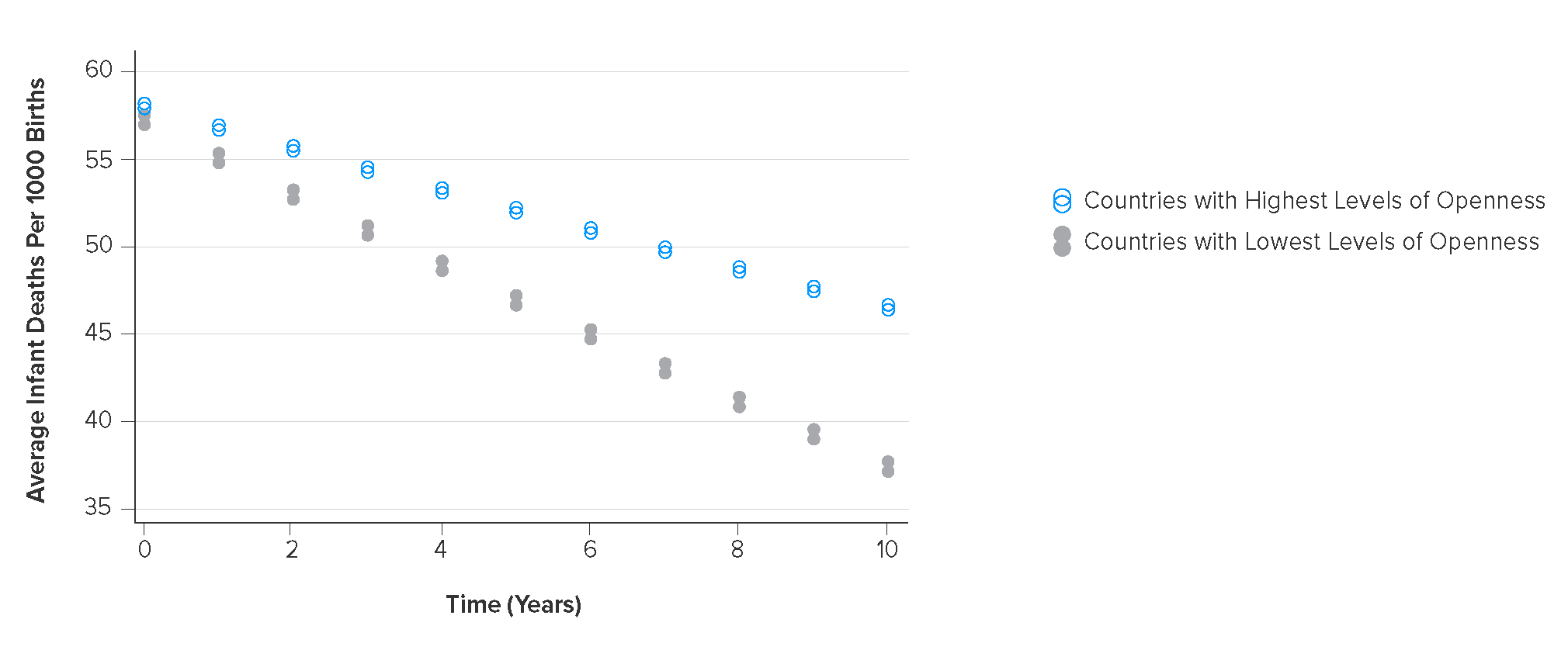

Infant mortality: Greater openness led to a measurable improvement in infant mortality rates, a reduction in 10 deaths per 1,000 births per decade between the most closed and most open countries. Over the course of decades, the result could be significant. (See Figure 3 comparing infant mortality between the most open and most closed societies.)

Life expectancy: Greater openness and accountability is associated with longer life expectancy for women and men in the medium- to long-term, with notably significant results over 10 and 20 years.

Figure 2: Diagonal accountability and other democratic institutions

Maternal mortality: The research did not find a statistically significant relationship between openness and maternal mortality. However, it is important to publish “non-findings,” as the lack of data may serve both future strategies and research. Additionally, it has been included here in the spirit of greater openness.

2. Education

Researchers looked at the impact openness had on years of education for the population 15 years and older. On average, adults in societies with the most diagonal accountability attain an additional year of schooling. Conversely, where accountability is weak, educational attainment falls behind. Notably, there is a 10- to 20-year lag for the effects of increasing diagonal accountability to make a difference.

3. Economics

Economic growth: The effect of openness on economic growth is positive and significant only with strong elections and strong checks and balances. However, diagonal accountability boosts the impact of both horizontal and vertical accountability at comparatively lower levels.

Economic equality: Countries with stronger civil society and free press have lower rates of inequality (lower Gini coefficient). This effect is smaller, but still statistically significant.

The social and economic effects of openness are stronger when there is stronger civil service, stronger complementary democratic institutions, and at higher levels of per-capita income. These findings have significant implications for the types of open government interventions and reasonable expectations of outcomes within OGP action plans and in general. The next section builds on the work of other transparency and accountability experts to identify when and why it works and how, even in imperfect situations, transparency can lead to improved accountability and performance.

Figure 3: Reduction in infant mortality in the most open versus most closed societies over time

When and how does open government work?

The evidence that openness works is growing. But the evidence from the V-Dem institute also shows that openness works best when it is part of a broader ecosystem of accountability and government capacity. The research prepared for this report showed the following:

Openness works better when there are stronger elections and checks-and-balances. Democratic institutions are mutually reinforcing. Where electoral systems are stronger, civil society and free press are more effective at informing voters. In turn, voters are more likely to increase pressure on elected officials for results. Where oversight institutions are strong, again, public participation and access to information are predictive of better development outcomes.

Openness has a stronger effect when countries are wealthier and when the civil service is competitive and impartial. Mass mobilization has been credited with governance change in countries around the world. The Philippines’ People Power movements are a good example of where civil society action by itself led to changes in leadership. However, far more typical are examples like the Republic of Korea’s, where mass demonstrations and the Constitutional Court contributed to a shift toward a government with a strong anti-corruption platform. When civil society and other institutions work together, they tend to be more effective.

Even when countries have lower income or low levels of accountability, openness can improve state capacity. Free press and free civil society have a positive effect on the quality of civil service. This has significant implications for any one-size-fits-all approach to open government, especially in the least-developed countries or undemocratic countries. It suggests that openness will have a more indirect immediate effect on development outcomes, but is an integral first step in improving government function.

This data reaffirms the growing consensus that openness works. However, “transparency alone is not enough,” is also a common refrain. So, what makes transparency “enough” to change behavior? As the report will discuss, the answer requires the development and use of both formal and informal mechanisms of accountability.

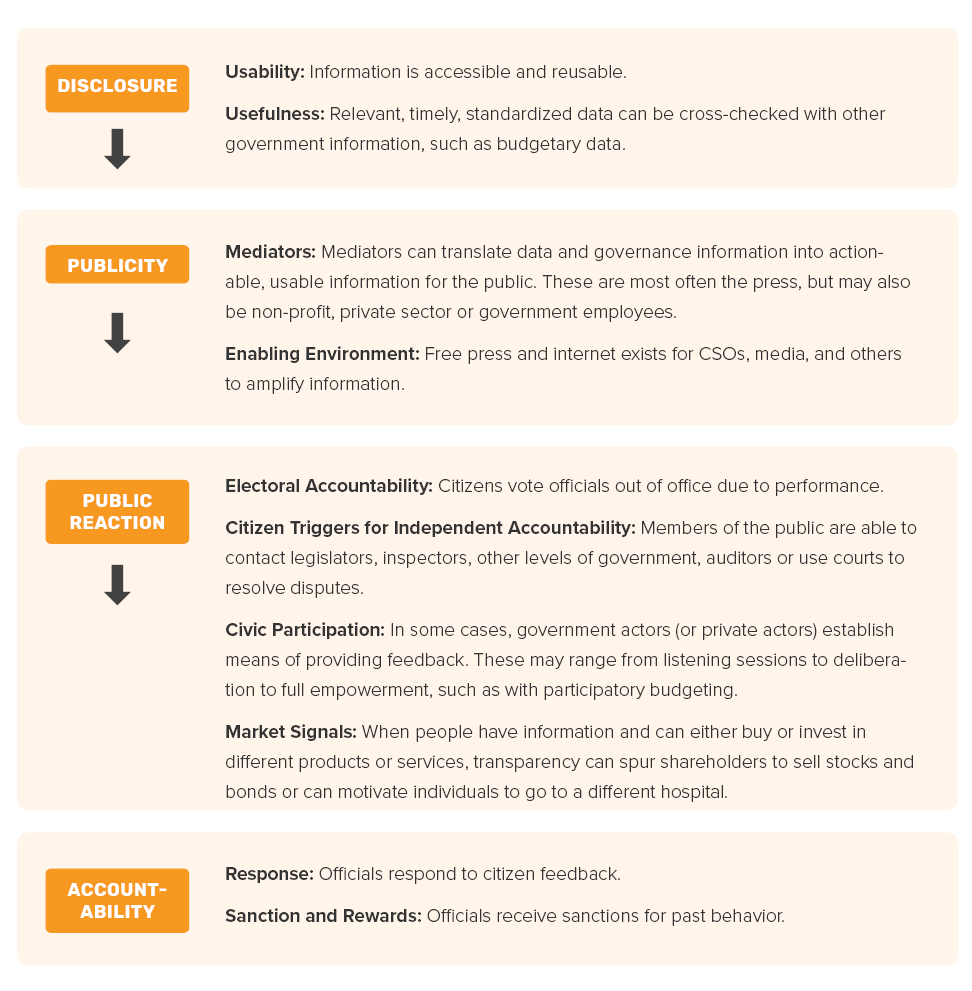

Toward intentional accountability

An overall finding of this report is that many commitments, especially in public services, assume that information disclosure will result in improved performance, responsiveness, or accountability. While two-thirds of OGP commitments have some element of transparency, less than a third mention accountability, and of those, nearly half do not describe the actual means of achieving accountability–whether through courts, audits, complaint mechanisms, elections, or seeking services via alternative means.

These are, in essence, “black box” accountability commitments where there are inputs (in our case information), some unspecified process, and, shortly thereafter, accountability. By contrast, there are “glass box” accountability reforms, wherein information is disclosed and members of the public have a clear channel (or channels) to inform, persuade, or otherwise convince the government to act. In some cases, these commitments may promote accountability because the conditions for accountability are strong. In other cases, they may fall short. What exactly are those conditions?

Many have already mapped out the link between transparency, participation, and accountability.20 This publication does not seek to replace or refute those models. Instead, its primary goal is to advance ambitious, credible reforms, and help move OGP action plans from transparency to accountability–from black box to glass box accountability.

Figure 4 shows four conditions under which transparency leads to greater accountability. Importantly, it does not limit means of accountability and citizen action to the work of non-governmental organizations but to the functioning of a variety of institutions. (The diagram relies heavily on work by Jonathan Fox, Tiago Peixoto, and Alasdair Roberts.)

Better clarifying the theory of change behind open government reforms can help lead to greater impact and lead to more significant improvements.

The who: Commitments should lay out the use cases for newly disclosed information: Who will be accountable to whom if the information is released?

The how: Where possible, those commitments should articulate the channels through which transparency will take place: The market? Participatory opportunities? The courts? During electoral campaigns?

The if: Commitments should reflect the current state of institutional accountability: Does the enabling environment exist in which people can safely use the information to criticize officials or change service providers?

These are the essential questions in assessing whether, and how, OGP action plans have achieved their goals. It is through this lens that reformers must view their future efforts, including public policy. In the accompanying sections, this report will look in detail at three core policy areas: anti-corruption initiatives, civic space, and public services.

Figure 4: Transparency depends on other institutions and conditions to lead to accountability

Global trends

Before examining policy-specific findings in other sections or modules, this section looks at global open government trends, as well as collective findings from OGP countries. The most significant transformations that openness brings are often measured in decades, rather than months or years. This means that the long-term impact of many current open government reforms may not yet be known, even where they have been successfully implemented. Nonetheless, we are able to look at early results using the data assembled for this report.

Divergence, convergence, and parallel trends over time

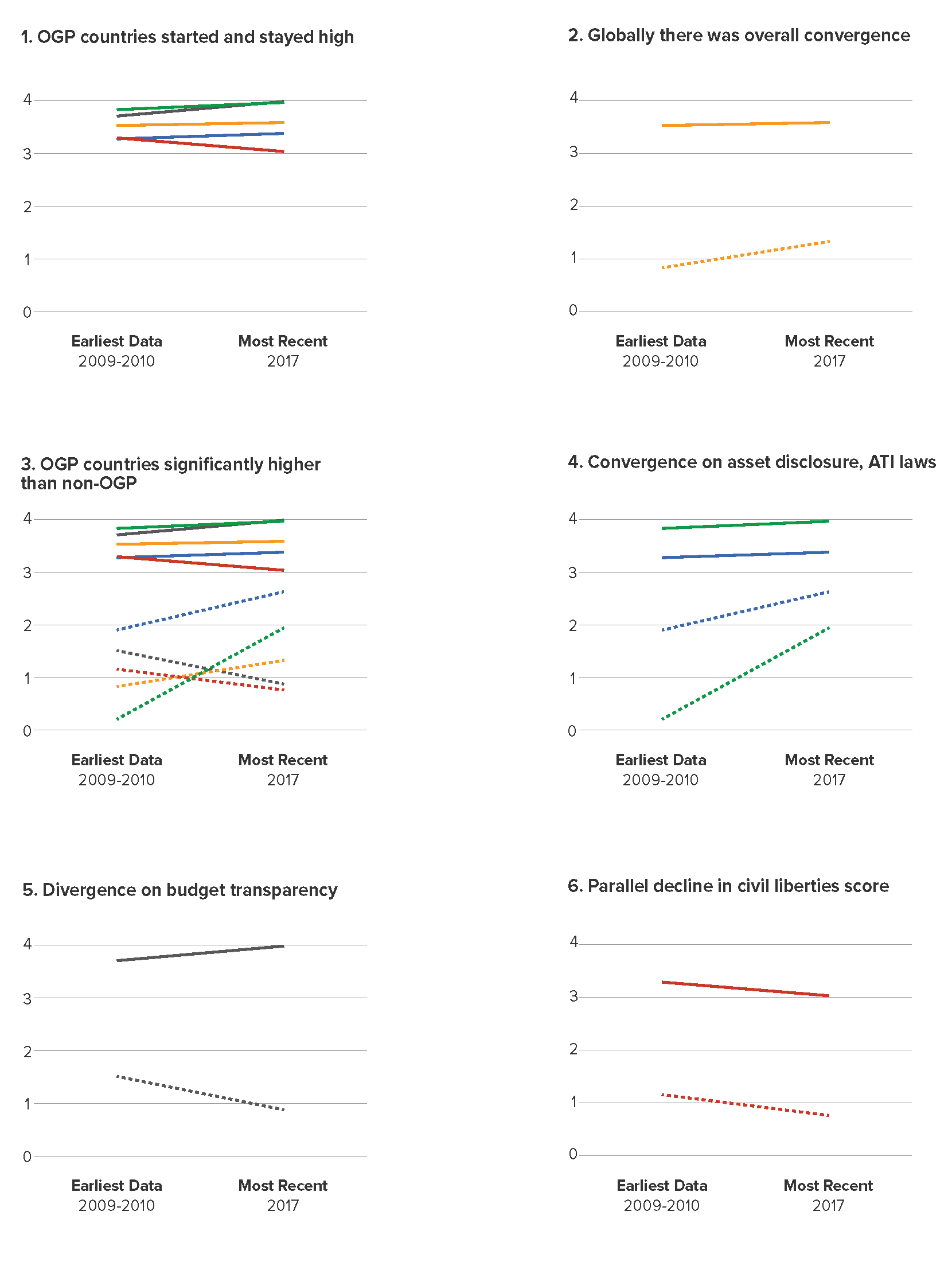

How do OGP countries compare across policy areas over time? Changes in eligibility requirements for countries that have been in OGP for more than five years suggests where there is progress and regress. Collectively, the indicators used for OGP eligibility are the most rigorous, transparent, and adequate proxies for actual performance. Moreover, they are generally accepted and referred to by organizations working on open government and related issues.22 The four eligibility requirements use indicators that represent major areas of work in OGP:

Fiscal openness: availability of executive budget proposal and audit report (Source: Open Budget Survey)

Access to information: existence of legal framework for access to information (Source: right2info.org and rti-rating.org)

Anti-corruption: asset disclosure by public officials (Source: World Bank database: Public Officials’ Financial Disclosure)

Civic participation: civil liberties (Source: Economist Intelligence Unit, EIU Civil Liberties Index)

The findings are shown in figures 5.1-5.6 (following page). They compare the 42 countries that have been in OGP for more than five years to non-OGP countries.

- OGP countries started and finished with high scores, generally higher scores in the four eligibility areas and overall. See figure 5.1.

- On average, more open government policies are in place according to the narrowly defined overall eligibility scores. (See figure 5.2.)

- When comparing OGP across policy areas, OGP countries continue to significantly outperform non-OGP countries. (See figure 5.3.) While this is not surprising, it at least establishes that there was not a marked decline among OGP countries.

- There was global convergence around access to information law passage and asset disclosure. (See figure 5.4.) Whether this convergence proves that “improvements would have happened without OGP” discounts global norm-setting functions of OGP. It also does not prove that it happened because of OGP, only that there are emerging norms here.

- There was global divergence around the open budget requirements (publication of executive budget and audit report). While almost all OGP countries now had a perfect score on this between 2017 and 2018, many other countries are regressing. (See figure 5.5.) This squares with the evidence on OGP’s consistent high performance in budget transparency as observed by the Independent Reporting Mechanism. (See following subsection, “High-Performing Policies.”)

- There was a troubling parallel downturn in civil liberties among both OGP and non-OGP countries. (See figure 5.6.)

Figure 5: Global open government trends among OGP and non-OGP countries

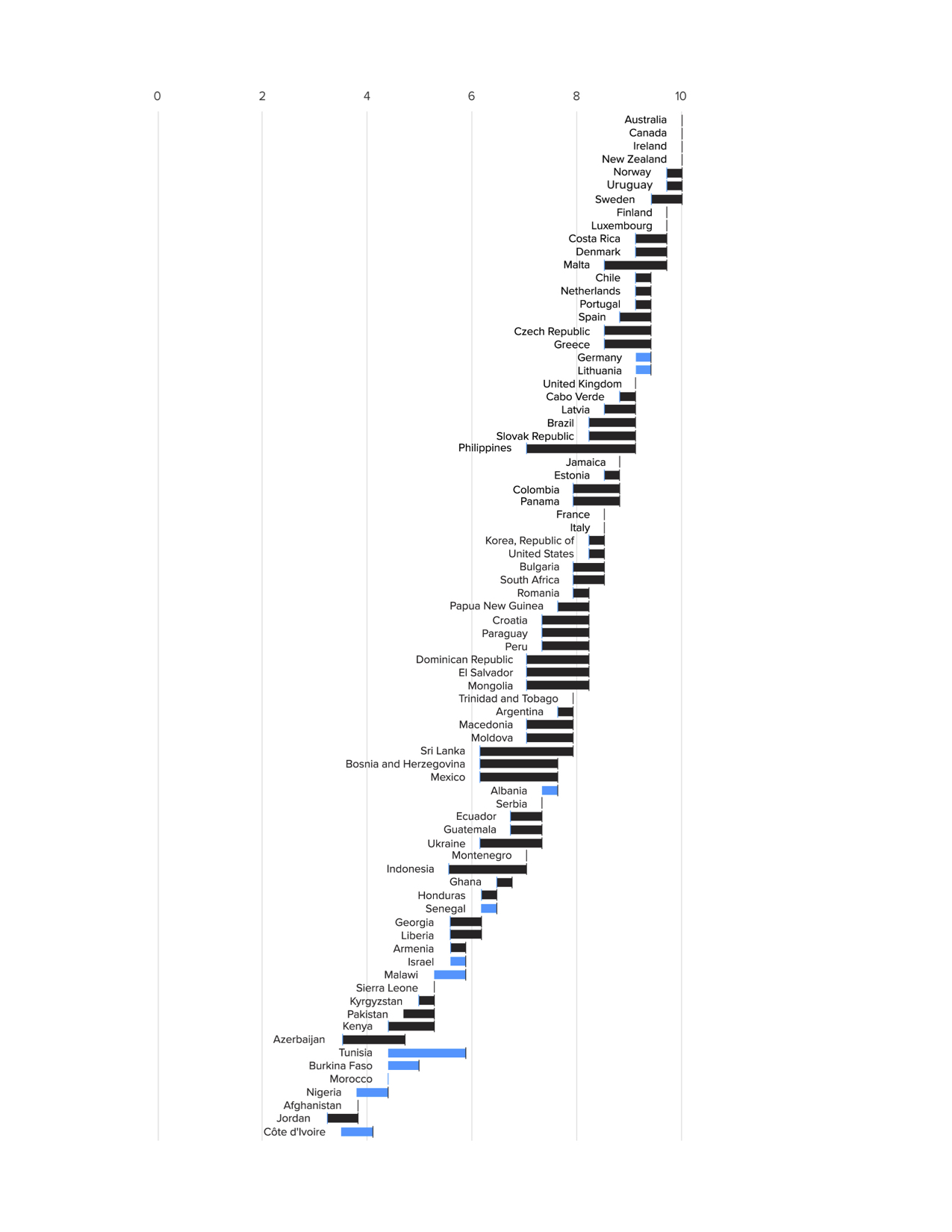

The troubling decline in civil liberties

The decline in civil liberties scores is of particular concern as civic space is fundamental to the functioning of open government of OGP. How robust is this finding and what is causing it?

The slide is not in every country, but it is nearly universal. Using the same Economist Intelligence Unit data, the global median and mean have shifted left, or declined, between 2011 (Figure 5.1) and 2017 (Figure 5.2). This has even occurred, however minutely, in traditionally high-scoring countries, including in countries considered to be traditionally strong democracies.

While the decline continues to be troubling, there are indicators to suggest that it can be mitigated and focusing on open government reforms is working:

- While the change in absolute terms is the same, relative to the initial starting point, OGP countries have fallen less (in pure percentage terms.)

- As a percentage change, OGP countries have declined less in relative terms (as a total percent) than the non-OGP average. This may be cold comfort to some.

- During a time of civil liberties declines, OGP may still be outperforming the global average. The relative drop suggests that OGP countries are at least not declining more quickly than non-OGP countries, which would certainly be cause for alarm. Given the shifts in some of the world’s largest countries, which are part of OGP (Brazil, Mexico, Pakistan, Philippines, and the United States), this finding is unsurprising, but noteworthy. It is offset, to a small extent, by improvements in countries such as Nigeria, Kenya, and South Korea.

- This finding is consistent even when using indicators other than the EIU Score. While there are inherent issues with the EIU Civil Liberties Score (lack of transparency in method and underlying data among them), this finding holds up with robustness checks across other indicators, such as time series analysis of V-Dem’s CSO Entry and Exit indicator and CSO Repression.

- The declines in many democracy indicators (especially non-electoral indicators) are alarming. However, when viewed over the course of decades, democratic institutions still remain near an all-time high in terms of indicators of liberal democracy (elections, respect for rights, and checks on executive power).24

Despite the tempered progress seen among some OGP countries, as the “Innovations to Norms” section in this report shows, there can be little argument that OGP countries can and should continue to use their action plans to promote and protect fundamental civil liberties through their action plans.

Source: The Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) Democracy Index, Civil Liberties (CL), n=79

Figure 6: OGP countries experience decline on civil liberties

Changes in OGP country scores on the Civil Liberties (CL) indicator from The Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) Democracy Index. Comparisons are between scores in 2011 and 2017. Visit EIU Democracy Index to access the underlying data.

General recommendations

This first-ever, world-wide assessment of OGP efforts produced a significant amount of new findings, capturing both commitment successes as well as notable areas for growth. Importantly, they offer lessons which allow OGP countries to chart an even more strategic path forward.

Building off of this work, what follows are recommendations specifically tailored to meet the needs and contributions of key OGP constituencies. Collectively, these important groups will be responsible for co-creating and implementing critical future reforms.

For governments:

Ensure commitments reflect national priorities. Continue to identify issues of national and local priority, even if those are not part of the policy areas explored in this report. These have a high-impact and play to OGP’s strengths of matching each action plan to the local context.

Consider OGP high-priority areas. Identify areas where your government or civil society groups can play a leadership role. In particular, civic space has a strong asymmetry between what is needed and what is in action plans. For countries with new initiatives or works in progress, identify leaders and support structures within OGP which might help to ensure ambitious, credible implementation. For countries which do not have commitments in an area where performance data suggests improvements, identify commitments which might advance this work.

Continue to prioritize civic space. The data is fairly clear that there is a reversal in civic space, even within a “club of the committed” like OGP. As (one of) the world’s leading forums in advancing this foundational element of democracy, identify innovative steps to ensure respect, protection, and promotion of these fundamental rights.

Make accountability more intentional. Move beyond “black box” accountability by incorporating explicit strategies and mechanisms to make transparency count for improving responsiveness and performance.

Move from project-based accountability to institution-based accountability. The cases of Mongolia in education and Brazil in health show that setting up permanent monitoring institutions where citizens have seats at the table and voices in the room have better results.

Involve the underserved. Engage ministries that represent parts of the population or groups of citizens that may otherwise be left out of the conversation regarding open government, corruption, and services. These could include women, youth, and people with disabilities.

For national level advocates:

Coalesce around national priorities. Identify policy areas within your country where there is a nexus of political ambition and your own advocacy goals. Ideally, this report helps share innovations and gaps in current policy and practice across borders.

Leverage advocacy expertise. Continue gathering evidence, initiating dialogue, and advocating reform in critical policies. The examples of European Centre for Non-profit Law in working to assure freedom of assembly and the many African organizations working with government to strike a balance between anti-money laundering rules and freedom of association can serve as some inspiration in civic space.

Use existing mechanisms. Identify and advocate on international conventions and existing commitments which have open government implications, and that may have been ratified but not yet implemented. An example would be the Convention to End Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW).

Ensure end-user involvement. Make certain that advocacy for data includes potential users, especially journalists. Our evidence shows that data for accountability works better when end-users are involved in the design and publication of data.

For international organizations:

Continue production of cross-national data on decision-making. In particular, more data is needed on the levels of transparency of decisional documents (plans, budgets, drafts, decisions), the level of participation, and the presence of public complaint mechanisms within key policy areas.

Rely on, and use, the data. Use OGP cross-national data to identify binding constraints around core governance themes to: (1) better target areas that governments have already signaled as being politically important; (2) identify binding constraints within particular countries; and (3) identify potential champions who would be able to share approaches that worked in their countries.

Produce and use sex-disaggregated data. Collect sex-disaggregated data regarding budgets, services, and participation when applicable. Encourage governments and civil society organizations to collect sex-disaggregated data as well.

For researchers:

Use OGP data. OGP has published all of its data, including data from the Independent Reporting Mechanism and third parties into a single database in the hope that researchers will better be able to understand where reforms are successful and where they need continued effort. In addition, it may illuminate OGP’s impact to a greater level of specificity than it has in the past.

Utilize the impact evaluation. This report touched on a number of relationships between open government and OGP in changing people’s lives. More sophisticated research on causal links, wider scope of analysis on different topics, and attention to inclusion are just three of the areas that could be better explored in this area.

Centralize and promote good practices and standards. The work of academics and think tanks has been invaluable to the success of this report. The continued attention to the design of good policies around civic space, public participation, when (and how) transparency is most effective for accountability, reductions in corruption, improving lives, and rebuilding trust is key.

Take gender into account. When evaluating reforms, measuring impact, or creating good practices and standards, think about how the lives of men and women, boys and girls are different and how they interact differently with government. Women’s relative lack of political and economic leverage reduces their ability to demand accountability or to highlight their specific experiences and concerns.

For everyone:

Reach out to OGP for support. Please do not hesitate to contact the authors of this report with queries, corrections, suggestions for future editions, and topics for what the authors hope to be a series of analytical papers. The world of open government is a beautiful, and sometimes frustrating, patchwork of knowledge, relationships, and individual reformers. It works better when people are in touch and can offer to share. Good ideas come from everywhere.

1 Anna Lührmann & Staffan I. Lindberg (2019) A third wave of autocratization is here: what is new about it?, Democratization, https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2019.1582029.

2 Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Institute, Democracy for All: V-Dem Annual Democracy Report, (Gothenburg, Sweden: V-Dem Institute, 2018) 26, https://www.v-dem.net/media/filer_public/3f/19/3f19efc9-e25f-4356-b159-b5c0ec894115/v-dem_democracy_report_2018.pdf.

3 V-Dem Institute, Democracy for All: V-Dem Annual Democracy Report, 26.

4 World Justice Project, “Open Government Around the World” (accessed 31 Jan. 2019), https://worldjusticeproject.org/open-government-around-world.

5 Economist Intelligence Unit, Democracy Index 2018: Me too? Political Participation, Protest and Democracy (2019), https://www.eiu.com/public/topical_report.aspx?campaignid=Democracy2018.

6 Edelman, 2019 Edelman Trust Barometer (20 Jan. 2019), https://www.edelman.com/trust-barometer.

7 Thomas J Bollyky et al., “The relationships between democratic experience, adult health and cause-specific mortality in 170 countries between 1980 and 2016: An observational analysis,” Lancet 393(10181) (13 Mar. 2019) 1628–1640, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30235-1.

8 Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson, Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty (New York: Crown Business, 2012).

9 Many other reports cover the relevance of international and domestic case law on the fundamental nature of these rights in a more thorough, readable, and relevant manner than this report could. See for example, Kravchenko and Bonine, Eds. Human Rights and the Environment: Cases, Law, and Policy. Carolina Academic Press.

10 Munyema Hasan, Skeptic’s Guide to Open Government (Washington, DC: Open Government Partnership, 2018), https://www.opengovpartnership.org/resources/skeptics-guide-open-government.

11 United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), Guidebook on anti-corruption in public procurement and the management of public finances (Vienna: United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime, 2013), https://www.unodc.org/documents/corruption/Publications/2013/Guidebook_on_anti-corruption_in_public_procurement_and_the_management_of_public_finances.pdf; Gavin Hayman, “#Busted: The many myths of why government contracts should not be published” (Washington DC: Open Contracting Partnership, 20 Jul. 2018), https://www.open-contracting.org/2018/07/20/busted-many-myths-government-contracts-not-published/.

12 Stephan Grimmelikhuijsen, “Being transparent or spinning the message an experiment into the effects of varying message content on trust in government,” Information Polity 16 (IOS Press, 2011) 35–50, https://dspace.library.uu.nl/bitstream/handle/1874/231701/BeingtransparentGrimmelikhuijsen.pdf?sequence=1.

13 Zdenek Drabek and Warren Payne, “The impact of transparency on foreign direct investment,” Journal of Economic Integration 17 (2002) 777-810; Gaston Gelos and Shang-Jin Wei “Transparency and international portfolio holdings,” The Journal of Finance 60(6) (2005); Rachel Glennerster and Yongseok Shin, “Does transparency pay?” IMF Staff Papers 55(1) (International Monetary Fund, 2008), https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/staffp/2008/01/pdf/glennerster.pdf.

14 Iza Lejárraga and Ben Shepherd, “Quantitative evidence on transparency in regional trade agreements,” OECD Trade Policy Papers No. 153 (OECD Publishing, 14 Jun. 2013), https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/5k450q9v2mg5-en.pdf?expires=1557317166&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=E8C8A30EC3E10E1ED2EDA98401343183.

15 Carolin Geginat and Valentina Saltane, “Transparent government and Business Regulation,” Policy Research Working Paper No. 7132 (World Bank, 2014), https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/20698?locale-attribute=en.

16 James Hollyer, B. Peter Rosendorff, and James Raymond Vreeland, Information, Democracy, and Autocracy: Transparency and Political (In)Stability (Cambridge University Press, 2019).

17 Elif Arbatti and Julio Escolano, “Fiscal transparency, fiscal performance and credit ratings,” The Journal of Applied Public Economics 36(2) (2015).

18 Wendy Carrara et al., Creating value through open data: Study on the impact of re-use of public data resources (Brussels: European Commission, 2015), https://www.europeandataportal.eu/sites/default/files/edp_creating_value_through_open_data_0.pdf.

19 Nicholas Gruen, John Houghton and Richard Tooth, Open for business: How open data can help achieve the G20 growth target (Lateral Economics and Omidyar Network, Jun. 2014), https://www.omidyar.com/sites/default/files/file_archive/insights/ON%20Report_061114_FNL.pdf.

20 Albert O. Hirschman, Exit, voice, and loyalty: Responses to decline in firms, organizations, and states (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1970); Susan Rose-Ackerman, The Political Economy of Corruption: Causes and Consequences (World Bank, 1996); Guillermo O’Donnell, “Horizontal Accountability in New Democracies” J. of Democracy 9(3) (1998) 112−126; Adam Przeworski, The state and the citizen (prepared for International Seminar on “Society and the Reform of the State, Sao Paulo, Brazil, Mar. 1998) (6 Mar. 1998), https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228703581_The_State_and_the_citizen; Daniel Kaufmann, Aart Kraay and Pablo Zoido, “Governance Matters” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 2196 (Aug. 1999), https://ssrn.com/abstract=188568; Jonathan Fox, “The uncertain relationship between transparency and accountability” Development in Practice 17(4/5) (Taylor & Francis Ltd., Aug. 2007) 663−67; Harlan Yu and David G. Robinson, “The New Ambiguity of “Open Government” UCLA Law Rev. Disc. 59(178) (2012), https://www.uclalawreview.org/pdf/discourse/59-11.pdf; Tiago Peixoto, “The Relationship Between Open Data and Accountability: A Response to Yu and Robinson’s The New Ambiguity of ‘Open Government’” UCLA Law Rev. Disc. 60(200) (2012), https://www.uclalawreview.org/the-uncertain-relationship-between-open-data-and-accountability-a-response-to-yu-and-robinsons-the-new-ambiguity-of-open-government/; Stephen Kosack and Archon Fung, “Does Transparency Improve Governance? Ann. Rev. of Pol’l Sci. 17 (2014) 65−87, https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev-polisci-032210-144356.

21 Fox, “The uncertain relationship between transparency and accountability;” Tiago Peixoto, “The Relationship Between Open Data and Accountability: A Response to Yu and Robinson’s The New Ambiguity of ‘Open Government;’” Alasdair S. Roberts, “Making Transparency Policies Work: The Critical Role of Trusted Intermediaries” Suffolk Univ. L. Sch. Res. Paper No. 14-39 (11 Nov. 2015), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2505674.

22 For this exercise, there is a treatment group–OGP members–and a control group–non-OGP members (108 countries that have not joined OGP, regardless of eligibility.) This gives at least two action plan cycles to see a difference in OGP countries. Of course, absolutely no claims of sole attribution to OGP are advanced.

23 Anna Lührmann and Sta ffan I. Lindberg, “Keeping the democratic façade: Contemporary autocratization as a game of deception” V-Dem Institute Working Papers 2018(75) (Gothenburg, Sweden: Varieties of Democracy Institute and University of Gothenburg, Aug. 2018), https://www.v-dem.net/media/filer_public/9c/6f/9c6fe0b9-7f78-4aac-8775-c1cccbd43df2/v-dem_working_paper_2018_75.pdf.