The Ottawa Hospital Case

The Ottawa Hospital (in Canada’s capital city) is building a new campus on the edge of downtown. Two previous efforts failed to secure a site because of public opposition. The third time, Hospital administrators began by consulting the community on the process, rather than the issues. “What would give people confidence in the Hospital’s planning decisions,” they asked? The discussion resulted in a “co-creation” or “collaborative” process that fit the circumstances. Some of the special features include:

- A central “Deliberative Group” of 23 community stakeholders, each representing a key community interest, as well as representatives from the Hospital, the City of Ottawa, and the Government of Canada.

- A commitment by all 26 Group members to follow basic “rules of engagement,” such as a willingness to listen to one another’s views, to work to find reasonable accommodation of their differences, and to defer to evidence.

- Inclusion of one of the Group’s co-chairs on the Hospital’s new campus planning committee.

- Development by the Group of a shared narrative that defines the community’s overall vision for the new facility, explains its role in the process, and frames the key issues for discussion.

- Holding a series of “conversations” with the community at large to help guide the Group’s deliberations and test and validate its findings.

This community engagement process is now in the second of a four-year program and has made significant progress on rebuilding trust between the Hospital and the community.

An Informed Participation Approach

The Ottawa Hospital case highlights the critical role of trust and goodwill in public deliberation, but it also shows how these, in turn, depend on finding the right balance between public participation and top-down decision-making. Informed Participation helps planners strike a balance that:

- Overcomes many of the usual barriers to meaningful public participation. It allows governments, citizens, and/or stakeholders to find solutions to complex public policy issues together, and in ways that build trust between them and resilience around the solutions;

- Establishes a “rules-based” approach to dialogue and deliberation, which ensures that discussion is disciplined and fair, and raises the standard of success from getting public buy-in for a solution to building public ownership for it; and

- Reassures public-sector participants that their roles will not be compromised. Informed Participation ensures that the objectives, scope, and rules of engagement are carefully crafted to fit the issues, which, in turn, addresses many of governments’ long-standing concerns about deliberative processes, and clears the way for public servants, citizens and stakeholders to collaborate with confidence.

Informed Participation Engages Different People Differently

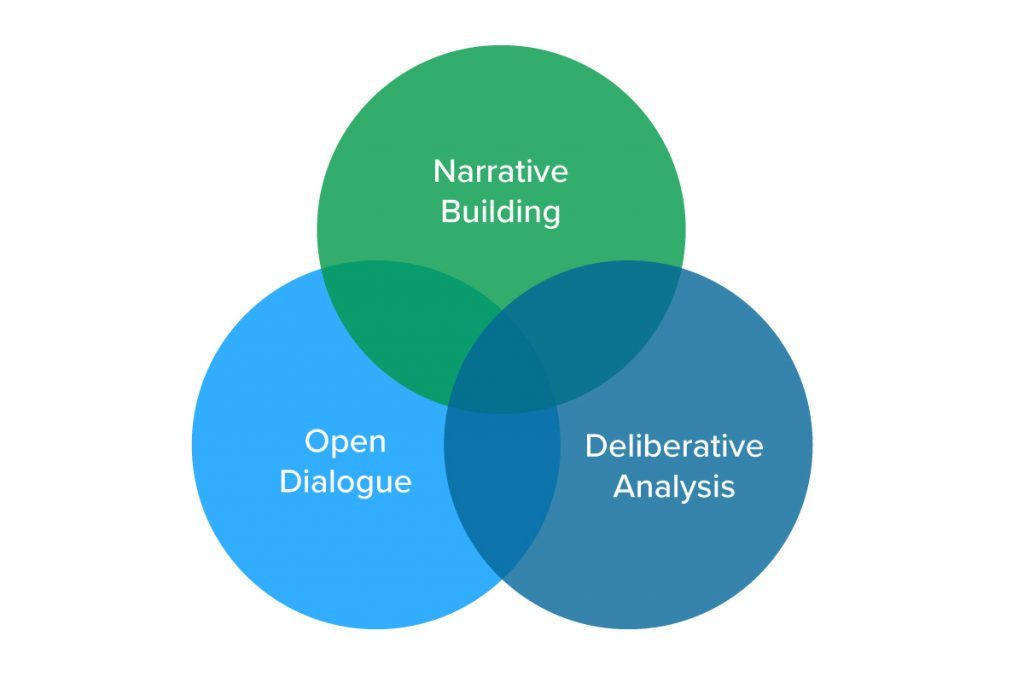

Deliberative discussions are not one-size-fits-all; they take different forms. For example, while experts often rely on facts and arguments to make their case, non-specialists are more likely to tell stories or offer examples. Informed Participation accommodates these differences through three different “styles” of deliberation, as follows:

Deliberative discussions are not one-size-fits-all; they take different forms. For example, while experts often rely on facts and arguments to make their case, non-specialists are more likely to tell stories or offer examples. Informed Participation accommodates these differences through three different “styles” of deliberation, as follows:

- Open Dialogue asks people to use their natural conversational skills to guide an exchange of views and search for solutions to an issue. Open Dialogue is often used in roundtables, conferences, and relatively informal gatherings.

- Deliberative Analysis sets out explicit rules to ensure that dialogue is disciplined, respectful, fair, and guided by facts and evidence. This dialogue style is often used in processes such as citizens assemblies and other, more formal deliberative forums.

- Narrative building asks participants to draw on their lived-experience: (1) as a source of ideas and evidence; and (2) to build stories and scenarios around important issues and challenges. Stories are important because they can explain difficult issues in ways that people understand and identify with and they can bring people’s lived experience into the decision-making process.

Informed Participation has been successfully applied and tested in a variety of projects in Canada and Australia, including the renewal of provincial condominium legislation, the development of a poverty reduction program in the Inuit territory of Nunavut, and the development of an ethical framework for Artificial Intelligence. As the insert below shows, Informed Participation is currently being used to develop Australia’s OGP action plan.

Australia’s OGP Action Plan

Informed Participation is guiding development of Australia’s third OGP action plan. The process uses all three deliberative styles (Open Dialogue, Deliberative Analysis, and Narrative Building), as well as techniques from other areas, such as design thinking.

The approach has helped the participants see process design in a new light. Informed Participation focuses attention on the relationship between tasks and processes. This has proven extremely helpful in setting the scope of the work, anticipating the processes to follow, identifying the people to be included, and setting the rules to guide discussion.

Informed Participation has helped the participants find opportunities for a win/win, where a more conventional process might have treated them simply as win/lose scenarios. The result is a higher level of collaboration between civil society and government than in previous processes.