Costa Rica Results Report 2019-2022

- Action Plan: Costa Rica Action Plan 2019-2022

- Dates Under Review: 2019-2022

- Report Publication Year: 2023

The results achieved in the implementation of this action planAction plans are at the core of a government’s participation in OGP. They are the product of a co-creation process in which government and civil society jointly develop commitments to open governmen... constitutes improvements from the previous cycles, partly thanks to the design of the commitments, which were specific and verifiable. The experience acquired in the involvement of civil society by the implementing bodies makes an increasing difference. There are still significant challenges maintaining the same level of participation achieved in the co-creation of the plan through its implementation. This is an aspect in which the National Commission can have a more direct influence by exercising greater leadership.

Early ResultsEarly results refer to concrete changes in government practice related to transparency, citizen participation, and/or public accountability as a result of a commitment’s implementation. OGP’s Inde... More:

Early ResultsEarly results refer to concrete changes in government practice related to transparency, citizen participation, and/or public accountability as a result of a commitment’s implementation. OGP’s Inde... More:

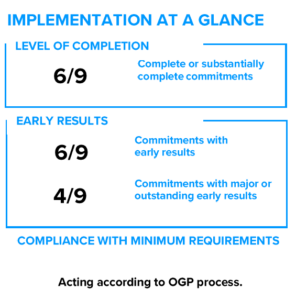

Four of the nine commitments included in the 2019-2022 action plan showed significant early results, although none achieved outstanding results. Two achieved marginal results, and three did not show results at the time of this evaluation. Such numbers are an improvement on the levels of early results from previous action plans, as almost half of the commitments contributed significantly to the opening of the government. These results lie in the effectiveness of several of the participatory processes and in the usefulness and use of the information shared on the initiative of the commitments.

In the Design Report[1] only commitmentOGP commitments are promises for reform co-created by governments and civil society and submitted as part of an action plan. Commitments typically include a description of the problem, concrete action... 8, related to the JudiciaryWhile a majority of open government reforms occur within the executive branch, OGP members are increasingly taking on commitments to increase the openness of the judicial branch. Technical specificati..., was classified as having the potential for transformative results. It proposed creating the Judicial Observatory. After the implementation, it was considered that it achieved significant results since it managed to publish useful information for unions such as journalists and lawyers, allowing to quantify the efficiency in processing cases and the judicial arrears. For this report, the commitment was not classified as outstanding because it is still early –just a year after its launch- to know the depth of the impact of this new tool, which will probably be greater in the future as it becomes known and more people use it.

CompletionImplementers must follow through on their commitments for them to achieve impact. For each commitment, OGP’s Independent Reporting Mechanism (IRM) evaluates the degree to which the activities outlin... More:

Two of the nine commitments were fully implemented, while four had a substantial level of completion, meaning that more than half of the commitments reached a level of substantial or higher completion. This represents an improvement from the previous cycle and makes Costa Rica’s fourth action plan one of the most widely implemented[2]. The two main factors that enabled this were the additional year granted by the OGP for implementation[3] due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and the number of commitments that were part of the strategic plans of the implementing bodies, allowing them to have a budget and personnel focused on their implementation. The commitment in charge of the Judiciary, classified with the potential for transformative results, was completed.

The initiatives that achieved the lowest levels of completion were those assigned to offices of the implementing institutions that had other priorities or could not overcome setbacks caused by the pandemic, such as the obligation to do without face-to-face and rely on technological resources to carry out implementation processes virtually. Regarding the thematic areas, the action plan contemplates a varied spectrum of initiatives that include areas such as security (commitment 7), in which early results were shown, educationAccountability within the public education system is key to improving outcomes and attainment, and accountability is nearly impossible without transparent policies and opportunities for participation ... (commitment 1), decarbonization in the fight against climate change (commitment 3) and economic recovery (commitments 2 and 6). All of them were important within the national agenda and had the potential to impact broad segments of the national population.

Participation and Co-creation:

The process to develop the fourth action plan achieved the highest number of participants of all the co-creation processes that Costa Rica has had, with more than 1,100 people[4], including those who participated through digital media. It was also the best documented co-creation process, with the most information available and perhaps the most robust in terms of monitoring and availability of information while it was taking place. It had reports published on the national open government page that informed each subsequent stage of the process, and a methodology built from the definition of specific problems developed collaboratively in face-to-face workshops that totaled more than 230 participants, including officials and members of civil society. It achieved a participation level of “Involve”, the third best of the Spectrum of Public Participation of the International Association for Public Participation[5].

The co-creation process was also more inclusive by having LESCO (Costa Rican Sign Language) interpreters in some of the face-to-face sessions of the thematic area work groups, and by awarding 10 scholarships for people from outside the metropolitan area to participate. A difference with previous co-creation processes was having had a significant amount of resources for its execution, thanks to the fact that the technical proposal presented by ACCESA[6], a civil society organization, received a grant of USD$59,410[7]. The organization also had the advice and collaboration of other national and international non-governmental organizations in its leadership role during the co-creation of the plan[8]. As a result, a fourth action plan was received with specific commitments and clearly defined and verifiable milestones. Those milestones concern broad sectors of the national population and seek to address relevant problems for the country. Another result product of ACCESA’s valuable effort to systematize the lessons learned was the “Open government action plan formulation processes guidelines“, which will be helpful for future co-creations of these documents[9].

Civil society participation during the implementation was lower than during the co-creation processCollaboration between government, civil society and other stakeholders (e.g., citizens, academics, private sector) is at the heart of the OGP process. Participating governments must ensure that a dive..., except for some commitments. The commitments that achieved the highest levels of participation were those in which the departments responsible for implementing them had experience involving and working with civil society organizations: the National Commission for the Improvement of the Administration of JusticeTo address barriers that prevent citizens from having their justice needs met, OGP participating governments are working to expand transparency, accountability, and inclusion into all systems of justi..., the Office of Citizen ParticipationAccording to OGP’s Articles of Governance, citizen participation occurs when “governments seek to mobilize citizens to engage in public debate, provide input, and make contributions that lead to m... More of the Legislative Assembly, and the Ministry of Communication. Commitments delegated to departments that had to create new processes to engage civil society had limited participation with no verifiable influence on the outcome.

Implementation in Context

During the implementation of the action plan, there were a series of changes in the leadership of the agencies responsible for open government in Costa Rica and of the point of contact. This made it difficult to maintain the level of involvement of civil society organizations, academia, and the private sector accomplished during the co-creation of the plan. The Minister of Communication, responsible for leading the National Commission for an Open Government, changed three times during the three years that this action plan[10] was in force, while the person who initially served as the point of contact left the government without leaving no one else in the Open Government team. Some civil society organizations[11] believe that this caused a reassignment of responsibilities and work overload for some people[12] that would have impacted the monitoring and coordination of some of the implementation actions and the work dynamics of the National Open State Commission. Moreover, due to technical problems, the open government repositoryAccess to relevant information is essential for enabling participation and ensuring accountability throughout the OGP process. An OGP repository is an online centralized website, webpage, platform or ... was not online during the second year of implementation, so there was no publicly available information on the progress of the action plan agenda during the second half of its implementation.

The other situation that significantly delayed and limited the implementation of several of the commitments was the COVID-19 pandemic. The virtual conditions forced by the pandemic and the reassignment of tasks to attend to the emergency reduced the scope of action of several implementing institutions, which faced challenges in finding the availability and resources to complete the assigned tasks to comply with commitments and reconcile them with their other responsibilities.

Finally, Costa Rica faced a new presidential election process between February and April 2022, but this did not affect the implementation of the action plan commitments. By then, the commitments’ implementation actions that made the most progress had already been completed and those implemented to a lesser extent were previously discarded. The transition between the Executive officials responsible for the open government agenda happened smoothly and without major setbacks, thanks to the support of the civil society organizations from the National Open State Commission and to the fact that the outgoing point of contact remained within the government and closely followed the introduction of the new officials in charge of the matter.

[1] Costa Rica – Design Report 2019-2020, Independent Reporting Mechanism, May 2020.

[2] Costa Rica – Implementation Report 2017-2019, Independent Reporting Mechanism, May 2021.

[3] OGP, Criteria and Standards Subcommittee Resolution- COVID-19. https://www.opengovpartnership.org/es/documents/criteria-and-standards-subcommittee-resolution-covid19-pandemic/

[4] Interview with Geannina Sojo, point of contact during the co-creation process and first year of implementation, Ministry of Communication.

[5] The IRM adapted the “Participation Spectrum” developed by the International Association for Public ParticipationGiving citizens opportunities to provide input into government decision-making leads to more effective governance, improved public service delivery, and more equitable outcomes. Technical specificatio... (IAP2).

[6]Official Press Release May 31, 2019

[7] The resources came from the donor trust fund administered by the World Bank on behalf of the Open Government PartnershipThe Open Government Partnership (OGP) is a multi-stakeholder initiative focused on improving government transparency, ensuring opportunities for citizen participation in public matters, and strengthen... More.

[8] The organizations Costa Rica Íntegra, the Institute for Press and Freedom of ExpressionJournalists and activists are critical intermediaries connecting public officials with citizens and serving as government watchdogs, and their rights and safety need to be protected. Technical specifi... More (IPLEX), Plugin, Global Integrity and Kubadili also collaborated in the process.

[9] Manfred Vargas Rodríguez, with support from María Fernanda Avendaño, Accesa, September 2021.

[10] Carlos Soto, La Nación, May 2020.

[11] Álvaro Centeno, Open Government Office, Ministry of Communications, June, 2021.

[12] Perspective shared during the interviews, separately, by members of the civil organizations ACCESA and Costa Rica Íntegra.

Leave a Reply