Why Citizen Ownership Matters – Elgeyo Marakwet County

“I’ve liked the discussion today,” commented Alan Kipchumba, an Elgeyo Marakwet County-based contractor, “because the approach used was inclusive, thus participants represented various sectors and segments of society and gave opinions and discussed issues reflective of real-life experiences and not imaginations.” Mr. Kipchumba is referring to the citizen-led approach applied in developing Elgeyo Marakwet County’s Second Open Government PartnershipThe Open Government Partnership (OGP) is a multi-stakeholder initiative focused on improving government transparency, ensuring opportunities for citizen participation in public matters, and strengthen... More (OGP) Action PlanAction plans are at the core of a government’s participation in OGP. They are the product of a co-creation process in which government and civil society jointly develop commitments to open governmen.... His comments reflect a general belief by citizens that governments often take discretionary decisions. However, with confidence that his voice and that of fellow participants would count this time, he noted the role and value of a well-designed and executed civic engagement process.

Elgeyo Marakwet County, Kenya is one of fifteen pioneers in the OGP Local Pilot Program. The county developed its First Action Plan in 2016, which outlined four commitments to be implemented by December 2017. As a result of the pilot program, the county has made good progress in promoting access to information, as noted by the International Budget Partnership (IBP). Elgeyo Marakwet is the only county of Kenya’s forty-seven devolved units to publish 100 percent (all seven) of its budget documents as required by Kenya’s Public Finance Management Act of 2012. However, according to the OGP’s Independent Reporting Mechanism (IRM)The Independent Reporting Mechanism (IRM) is OGP’s accountability arm and the main means of tracking progress in participating countries. The IRM provides independent, evidence-based, and objective ..., none of the four Action Plan commitments was fully implemented on time.

Building a Platform for Community Engagement

As a participant in the design of the first action plan, I noted minimal interaction between citizens and government officials as the county prioritized its commitments. This also affected implementation because local communities had inadequate awareness and ownership of these commitments. My desire for the next co-creation processCollaboration between government, civil society and other stakeholders (e.g., citizens, academics, private sector) is at the heart of the OGP process. Participating governments must ensure that a dive... was therefore to build strong ownership of the new commitments among stakeholders. While designing the approach, I led the co-creation team to learn from and seek the inputs of multiple stakeholders on the design of the process itself, particularly by reflecting on the experience from the First Action Plan.

In essence, we learned that when communities own the process of identifying barriers impeding service delivery and their potential solutions, they not only feel more engaged, but the government is also fully aware that failure to live up to its promises will erode citizens’ trust. However, this requires platforms for citizens to provide input and oversight.

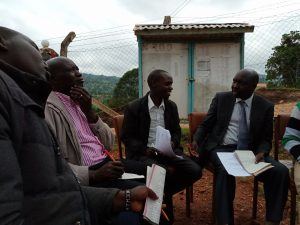

To provide such a platform, my team and I organized workshops (listening tours) in each sub-county. The idea was to put citizens at the core of the process and thus achieve a sense of community ownership.

Listening tours are made up of a series of participatory, deliberative workshops where one set of actors (e.g. government representatives) listens to another set (e.g. citizens) to understand its concerns, challenges, and aspirations, with minimal interruption. We could not fully implement the community listening tour strategies as desired because it was difficult to mobilize the target government officials as scheduled. Therefore, we had to adjust timelines and strategies to accommodate them.

We broke the listening tours into two parts – one, where communities led the process while the government officials listened; and, two, where top government officials responded to community issues and provided their own perspectives. The latter process was further broken into two parts – targeted meetings between with government officials in their offices to discuss issues raised by communities and county level meetings that brought together delegates from the community workshops, government officials, the multi-stakeholder forumRegular dialogue between government and civil society is a core element of OGP participation. It builds trust, promotes joint problem-solving, and empowers civil society to influence the design, imple... and civil society. This story focuses on the community listening tours.

The starting point for me and the team was to determine who would participate in the community workshops and how to select them. In consultation with the county’s multi-stakeholder forum, we opted to allocate representative slots to organized groups as follows: forty for youthRecognizing that investing in youth means investing in a better future, OGP participating governments are creating meaningful opportunities for youth to participate in government processes. Technical ... More organizations; twenty for civil society organizations; twenty for faith-based associations; twenty for elders’ associations; eight for academia; and eight for persons with disabilities).

I could not identify women’s groups from which to pick delegates, thus to ensure women’s representation, the groups listed above were asked to observe genderOGP participating governments are bringing gender perspectives to popular policy areas, ensuring diversity in participatory processes, and specifically targeting gender gaps in policies to address gov... More and regional balance as they picked their own delegates. The result was representation of all of the county’s twenty wards, with 450 individuals involved in the co-creation process, of whom thirty percent were women. Each of the ten county departments participated.

Letting Each Voice be Heard

Each workshop followed a similar format to ensure standardized outputs that could be compared across sub-counties. The agenda was structured in three parts, as shown in the diagram below.

Each workshop included focused discussions guided by standard templates, designed to prompt participants to think critically and identify the issues most important to them. We ensured that the process was moderated and facilitated by experts, but that citizens ultimately steered the agenda.

I observed that participants had ample time to freely express their concerns, understand each other’s perspectives and value each opinion, instead of just focusing on a defense of personal interests or a rebuttal.

Chelagat, a participant in the Keiyo North sub-county workshop, argued, “The availability of data and information is not sufficient for ordinary citizens to make tradeoffs between one budget priority over another in the absence of sufficient capacity to understand the available choices.” She made her argument while fellow participants listened. This illustrates that listening tours create a conducive environment for participants, regardless of gender and status in society, to think critically and build a case – beyond personal interests – on why certain open government ideas are more impactful than others .

Where do we go from here?

The workshops allowed citizens to own the process of generating ideas, share their aspirations and develop expectations around the implementation of commitments. Going forward, the biggest challenge is for us to demonstrate that, “a shared ownership of commitments among stakeholders as a result of robust co-creation is also a motivation for better implementation.” It is desirable to maintain the same vigor with which citizens participated in the co-creation process throughout the implementation stage.

The more frequent and effectively structured the opportunities for civic engagement are, the more valuable they can be. As Mrs. Beatrice Chesire, representing the Kenya Primary School Heads Association (KEPSHA) commented, “I’d wish that the forums are held frequently so that our participation earns something [makes a difference]. And it will be our joy so that the day is counted [as well spent].”

However, there is a need to strengthen the capacity of community organizations, and provide tools for social accountabilityTransparency of public service delivery is not enough on its own; giving citizens opportunities to monitor progress on the ground and hold their governments accountable improves the quality of these s... initiatives. We hope to partially address this need by developing a public portal to enhance access to opportunities to participate in implementation. Overall, our aim is to create a space for interaction where citizens can share their public comments and queries with the government, thus promoting greater accountability.

I realized from the co-creation process that when citizens are accorded space and assured that their voices will count (as in our listening tours), citizens become more optimistic, and their trust in government grows. As proclaimed by Mr. Arap Rukut, “Some of us had doubts about the future, but from today’s engagement, if our ideas are implemented, I can forecast good progress being made in developing the county over the next ten years.”

In conclusion, I would like to challenge the OGP community to nurture such hope for a better future, so that we can build a critical mass of optimistic societies that proactively hold their governments to account on the basis of trust. One way to do this is to reflect on post–action plan development practices. We still need to answer questions such as: What happens after action plan development? Even with a shared understanding and ownership of the commitments and greater expectations by citizens, what complementary mechanisms are necessary to expand the role of citizens beyond the development of an action plan – with ambitious commitments?

Leave a Reply