Seven lessons learned on making governance and public sector management investments work

This post was originally published at the Asia Development Bank’s blog.

ADB has a growing and active governance and public sector management (PSM) agenda. In recent years, ADB’s investments in public sector reforms in its developing Asia and the Pacific have increased more than 60%, from $1.59 billion in 2014 to $2.6 billion this year. These investments have covered from public expenditure and fiscal management to reforming state-owned enterprises and strengthening local governance.

Quarantine inspection in the PRC.

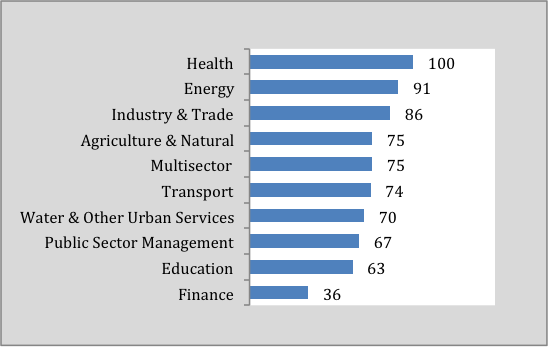

However, even as the size of the investments has increased, operational performance could be better. An assessment of project success rates for 2012-2014 carried out by ADB’s Independent Evaluation Department in 2015 showed the success rate of PSM operations to be 67%, on par with sectors like educationAccountability within the public education system is key to improving outcomes and attainment, and accountability is nearly impossible without transparent policies and opportunities for participation ..., and water and other urban services, but still a significant improvement from the 48% rate of success of 2010–2012.

Where PSM interventions have succeeded, results have often been transformative, with system-wide benefits. In this sense, PSM interventions have high-risk/high-return characteristics.

ADB Project Success Rates, 2012-2014. Source: IED, Annual Evaluation Review 2015.

Here are seven lessons that can be learned from ADB’s experiences as well as of others similar organizations from their operations to support governance and PSM reforms across developing countries in Asia and the Pacific.

1. Stay for the long haul. Governance reforms take a long time to yield results, largely because development is about behavioral change and this is time-inelastic. Whole institutions need to change and this requires consistency and development partners staying the course. It makes little sense to conceptualize, design, and implement a governance program and then vacate that space after a few years just because there are no immediate returns from that particular investment. ADB’s governance programs in Bangladesh and Nepal, for example, were initiated in the late 2000s but are only now beginning to yield the desired results.

2. Understand the political economy and country context. This is imperative when programming for governance and PSM reforms. A large part of governance and PSM work in a country is a function of not just the politics and political context (since the realm of public policy stems from it), but also of the dynamic relationships among the actors in the socio-political space. Indeed, ADB’s experiences shows that PSM operations tend to perform poorly where operations in other sectors also perform poorly, which points to the importance of country context.

3. Beware of capacity gaps to implement reforms. This is a must. Although not confined to governance and PSM alone, weak local institutional capacity is consistently cited as a major reason for less successful ADB sovereign operations. In fragile countries in the Pacific or conflict-affected Afghanistan, Public sector reform programs still have a critical component of capacity buildingEnhancing the skills, abilities, and processes of public servants, civil society, and citizens is essential to achieving long-lasting results in opening government. Technical specifications: Set of ac... and institutional strengthening.

4. Appreciate the increasing use of country systems. This is being emphasized not only in hardcore infrastructure projects but also in broader and more macro-focused governance and public sector reform programs. As developing countries begin to substantially reform their procurement and safeguard systems, ADB is increasingly moving toward relying more on country systems to make its programs and projects more efficient and effective on the ground. For instance, ADB support for reform efforts in specific sectors in Indonesia and India—including on procurement—is increasingly being characterized by use of country systems.

5. Continue focus on technical assistance. ADB’s investments in large-scale infrastructure projects—or indeed even for policy-based reforms of the type seen, for example, in public expenditure management or fiscal consolidation and contingent liabilities – should in many instances be coupled with technical assistance to ensure that local entities can effectively manage the investments. This capacity building component is one of the defining features of ADB’s work. Technical assistance has covered areas such as asset management in infrastructure projects in Central Asia, developing capital markets in South Asia, and disaster risk management throughout the whole region.

6. Target service delivery improvements. Where the rubber hits the road, all governance and public sector reforms have to be evident through the efficient, effective, and equitable delivery of services to the public. While reforms in macro policies (such as the regulatory environment to spur business growth) are important, reforms that yield day-to-day improvements in the lives of the citizens are a better manifestation of the citizen-government interface. The primacy of improved service delivery then is a necessary outcome of governance reforms. Such improvements demonstrate to the average citizen that the government is working for the people; this inevitably leads to greater trust in government.

7. Seek political commitmentOGP commitments are promises for reform co-created by governments and civil society and submitted as part of an action plan. Commitments typically include a description of the problem, concrete action.... Finally, on-the-ground experiences have shown that unless there is sustained political commitment to the reform process—and its content—no governance and PSM program is likely to be successful. In that sense, political commitment to reforms is a necessary and sufficient condition for development effectiveness. To spur such commitment, regular consultations, and continuous engagement with all stakeholders help considerably, since they show the buy-in that reforms engender.