Introduction

Brazil’s open government journey is inextricably intertwined with that of the Open Government Partnership (OGP). After President Rousseff and seven other heads of state launched OGP in 2011, Brazil hosted the first OGP Global Summit in Brasilia. In 2025, Brazil will become the government co-chair of the OGP Steering Committee.

Leveraging open government values of transparency, participation, and accountability, Brazil has channeled important reforms through its OGP action plans. As of November 2024, Brazil has produced six national action plans and 130 open government commitments. The municipalities of Contagem, Osasco, São Paulo, and Vitória da Conquista as well as the states of Goiás and Santa Catarina have also joined OGP Local.

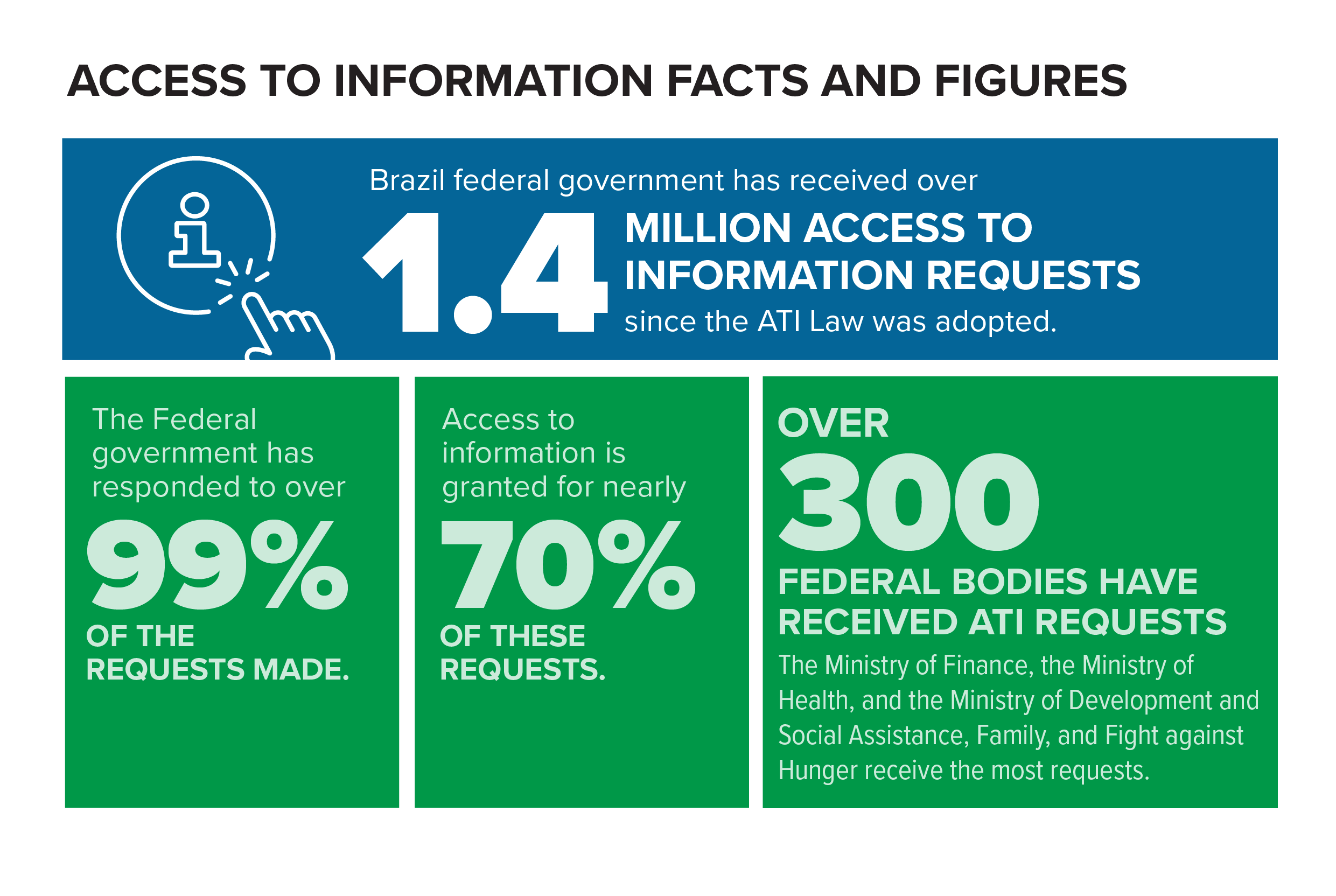

At OGP’s launch, Brazil sought to foster an enabling environment to implement its new Access to Information (ATI) Law. Its first and subsequent action plans addressed improvements to the e-Sic information request system—launched in 2012—and now to the Fala.BR platform. The National Open Data Infrastructure (INDA) guidance and Open Data Portal also came out of this first wave of commitments and remain core to Brazil’s open government efforts.

Brazil also launched a portal for public participation through its OGP action plans, now known as Participa + Brasil. With close to 380,000 users who have contributed 360,000 inputs from over 1,000 consultations to date, the portal has boosted public participation, including in developing Brazil’s OGP action plans. Soon, it will be incorporated into Brasil Participativo, a similar portal that already has over 1.5 million users.

The 2024–2027 four-year multi-annual plan (PPA) is regarded as one of the most significant experiences of civic participation at the federal level in Brazil. An academic said that allowing citizens to define and submit their own priorities for the PPA was a key achievement. The participatory process generated 8,254 citizen proposals and was accessed 4 million times through Brasil Participativo, underscoring the successful improvement of digital participation tools that have been supported by OGP action plans.

Yet, some of Brazil’s most ambitious action plan reforms have not always achieved their expected results. While early land governance transparency reforms were successful, more recent OGP commitments to increase transparency and oversight of land registries were less successful due to restrictions imposed by presidential decree during the Bolsonaro administration. In another case, a call for partners to support the implementation of transparency measures in the penitentiary system did not receive any applicants. Another commitment to harmonize health data standards across the country did not progress as it never received any endorsement from state and municipal authorities for implementation.

Engagement between government and civil society has been a key part of the open government process in Brazil as stakeholders try to build and maintain a diversifying multi-stakeholder process. This has led to new and varied topic areas in each action plan. This relationship and the OGP process were also largely maintained during the Bolsonaro administration despite the broader setbacks to civic space in Brazil. In the next section, we look at the commitment and leading role of the Comptroller General of the Union, and how it has built the relationship with civil society that is core to the open government ecosystem in Brazil.

We also highlight how Brazil has used the OGP process to implement its ATI Law. We examine how Brazilian stakeholders have used the OGP platform to develop and nurture open science from dispersed actions into a consolidated movement in pursuit of a national policy, and how the OGP framework has ensured environmental issues remain on the policy agenda in difficult political contexts. Finally, we investigate how the OGP process in Brazil has deepened and been enriched through the participation of local and state administrations—both through national and local action plans.

The Evolution of the Open Government Ecosystem in Brazil

The Comptroller-General of the Union (CGU) is the key coordinating body for the OGP process in Brazil. It plays a critical role in advancing open government, transparency, and anti-corruption measures in the country. Public institutions recognise its leadership position, and civil society notes that effective interactions with ministries on OGP matters happen primarily through the support of CGU.

A diverse group of civil society organizations (CSOs) is also key to the open government ecosystem in Brazil. While access to information is the most visible theme that is present in all action plans, the thematic scope of open government in Brazil has continued to expand. This has contributed to the diversification of non-government actors, which is key to the open government ecosystem in the country—ranging from business associations to CSOs working on themes such as racial equality and the aging population. Nevertheless, work remains to enhance the visibility of regional and underrepresented actors, including indigenous communities.

The relationship between government and civil society is complex and fluctuates as part of a broader challenge for civic engagement in Brazil. A government representative said that in its early years, CSOs approached the OGP action plan co-creation process with skepticism due to previous negative experiences in the way that the government handled civil society input. In 2014, following an IRM recommendation, CGU set up the Civil Society Working Group (GT) for advice on open government. Along with the Interministerial Committee for Open Government (CIGA), they constituted Brazil’s multi-stakeholder forum. Both government and civil society representatives recognize this was a key turning point in building mutual trust as its clear mandate and methodology outlined the roles and boundaries for public actors. Knowing their contributions would be respected and aligned with achievable goals, CSOs were able to participate in the OGP process with confidence—which helped foster a sense of shared ownership and accountability.

However, the open government ecosystem has not always experienced linear progression. Mechanisms for participation had been severely limited during the Bolsonaro administration, threatening civic space in Brazil. Even the 2019 presidential decree establishing the National Policy on Open Government limited itself to focus only on OGP (i.e., confirming the CGU’s mandate to coordinate the OGP process), rather than outlining a wider open government agenda. Yet civil society finds coordination and civic participation within OGP have broadly become more effective over time, with the OGP process viewed as a mechanism that brings about real changes, albeit remaining a work in progress amid financial and time constraints. A government representative said experienced CSOs became advocates for OGP by spreading awareness, strengthening trust, and consequently encouraging broader participation.

The OGP process in Brazil has evolved over successive action plans to include more government agencies beyond CGU. At the federal level, Brazil’s OGP ecosystem includes key actors across the executive, Superior Electoral Court of Brazil, Senate, and the Chamber of Deputies. More government agencies have also become accustomed to collaborating with civil society on open government initiatives, with ministries increasingly being more receptive to dialogue, according to civil society.

Despite the progress, there remains structural, institutional, and perception challenges that continue to limit the impact of OGP in Brazil. Civil society points to the fact that Brazil’s large size and regional disparities, coupled with limited funding, hinder OGP implementation especially in remote areas. A government representative stated that despite efforts to strengthen the OGP process, many open government efforts across government agencies are still fragmented and siloed. Meanwhile, civil society and academia stakeholders believe that all branches of government need to engage in more direct dialogue to strengthen the operational effectiveness of open government efforts. Many stakeholders agree that part of the difficulty lies in the fact that the concept of open government remains unclear to many public servants. They do not understand open government principles and therefore view transparency, participation, and open data as separate initiatives rather than interconnected strategies. The development of an Open Government Strategy that would push a whole-of-government approach is key to ensuring institutional and cultural changes.

The development of Brazil’s current OGP action plan has seen an influx of new civil society participants. After regression under the previous administration, President Lula has signaled a renewed commitment to open government. That said, civil society and academia pointed out that the use of rapporteur amendments to distribute federal funds during the Bolsonaro and current Lula administrations (dubbed “secret budgets”) have continued to be problematic in ensuring the transparency and accountability of government funding. Most recently, the Supreme Court directed changes to increase transparency in how officials transfer amendment funds. Brazil’s Transparency Portal now includes tools to help users find information about parliamentary amendments, beneficiaries, and spending documents.

Within the OGP space, the work of CGU to drive the creation and growth of an effective framework for engagement has included the expansion of the GT from three to nine CSOs and CIGA from 13 to 15 members. However, an academic stated that broader citizen engagement is limited by low public awareness and minimal media coverage of OGP. A government representative said continued efforts are key to transforming skepticism into active multi-stakeholder collaboration.

A Growing Number of Government Institutions Participate in OGPBrazil’s action plans cover a wide range of topic areas and each OGP action plan has included new government institutions. For example, the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs participated in 2013, the Central Bank in 2016, the National Road Transport Agency and National Water Agency in 2018, the National Treasury Attorney General’s Office in 2021, and the Ministry of Racial Equality in 2023. As shown here, 45 different government institutions have implemented at least one OGP commitment, and this number has grown steadily over time. |

Supporting Implementation of Access to Information through OGP

The right of access to information is enshrined in Brazil’s 1988 Constitution. While there had been efforts to improve transparency, it was not until 2011 that Brazil enacted an Access To Information (ATI) Law. The law was adopted thanks to then-President Rousseff’s personal political commitment to transparency, advocacy from civil society groups, media pressure, rulings from the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, and an added urgency due to the launch of OGP.

The law became a catalyst for shifting norms in Brazil’s governance and gave CSOs, journalists, and researchers a powerful tool to monitor and assess government activities. It reshaped behavior by transforming the ways in which public institutions, civil society, and citizens interact with government-held information. It also raised expectations for public access to government-held information across all levels of government. The legislative, judiciary, and some independent institutions, such as the Federal Public Prosecutor, have also enacted ATI regulations. CSOs started to use the ATI Law to push for greater accountability in areas like environmental protection. Even amid attempts to limit access to information during the COVID-19 pandemic, CSOs said they were able to push the government to release critical public health data. Furthermore, the cost for non-compliance, and mechanisms such as CGU’s Access to Information Monitoring Panel, encourage federal agencies to meet their obligations.

However, the introduction of Brazil’s Data Protection Law (LGPD) has created hurdles for transparency. Government agencies improperly cite LGPD as a reason to deny ATI requests or unpublish previously available information. CSOs said that public servants sometimes prioritize LGPD over the ATI Law due to its harsher penalties, leading to a regression in access to information, and that some institutions such as the armed forces and the judiciary have faced difficulties complying with the ATI Law, particularly when it comes to sensitive areas like personnel management.

Elsewhere, municipalities often lacked the technological infrastructure, regulations, and mechanisms to comply with the ATI Law. With over 5,000 municipalities across the country, many still have no proper channels for information requests. Even in states like São Paulo, civil society and government representatives alike say that the practices fall short.

Civil society acknowledges the supportive role of OGP in advancing access to information in Brazil, especially through international spotlighting and IRM assessments. They added that OGP has also facilitated networks and integration between the federal and municipal levels, which create opportunities for productive and continued multi-stakeholder dialogue.

Advancing Access to Information through the OGP Process

Access to information has been a consistent topic running throughout Brazil’s participation in OGP. Enhancing its implementation through OGP action plans has relied on the support and dedication of public servants as well as active monitoring and advocacy from civil society and the media.

Brazil approved its ATI Law shortly after joining OGP. Its first action plan (2011–2013) focused on strengthening access to information and proactive publication. This included commitments to advance the enabling environment to effectively implement the ATI Law such as capacity building for public servants, studying public demand for proactive disclosure, and developing a model to organize information services to citizens. At the time, the rapid pace of implementing the ATI Law even overshadowed the implementation of some commitments.

Results from other commitments, such as developing a National Open Data Infrastructure Policy and launching an Open Data Portal in collaboration with civil society, are still core to Brazil’s proactive disclosure regime, and subsequent OGP action plans continued to see commitments on open data. A civil society representative said the spread of proactive disclosure is one of the main achievements of the ATI Law, noting that the amount of public information available has exponentially increased since the law’s enactment.

Brazil’s second action plan (2013–2016) continued supporting the implementation of the ATI Law. The CGU developed an Access to Information Library that fostered greater understanding of the law, provided ATI requests and general statistics, and created a channel to appeal ATI decisions. Another commitment on the “Brazil Transparent” program successfully developed support materials and training for public servants on implementing ATI. A total of 1,630 municipalities had participated in the program by 2016. Another lasting outcome was the transparency index for municipalities and states which measures the compliance of state and local governments with the ATI Law’s proactive provisions.

In the third action plan (2016–2018), the Ministry of Transparency alongside multiple CSOs instituted a maximum deadline for answering requests and tracked compliance with that deadline. The collaboration also established evaluation methodologies for improving ATI implementation.

Research had found municipalities accurately responding to less than 25 percent of ATI requests and states to approximately one in nine requests. During the fourth action plan (2018–2021), Brazil launched the Fala.BR platform, which unified the implementation of ATI across states and municipalities to address the challenge of implementing ATI at the local level. The commitment’s success stemmed from a structured, milestone-driven approach that facilitated the development and broad adoption of the platform, therefore enhancing public access to government information. Key factors included strategic stakeholder engagement, technical feasibility assessments, robust support programs, and cost efficiency.

ADAPTING FALA.BR TO ALLOW ANONYMOUS ATI REQUESTSInitially proposed as an OGP commitment, the Fala.BR platform now facilitates information requests, manages complaints, controls deadlines for responding, streamlines communication, and can be adapted for local governments at no additional cost. It also introduced anonymous information requests—a game changer for journalists, activists, and anti-corruption advocates working on sensitive topics. Brazil’s third action plan sought to introduce anonymous requests but encountered significant legal challenges that prevented its direct implementation. In response, CGU and civil society collaborated to find an innovative workaround in Fala.BR. While the system receives and processes the requests and requestor’s personal information, as required by law, the agency responding to the request does not see the requestor’s identity. Some government stakeholders have highlighted this workaround as an indirect success of OGP, made possible by adapting to initial setbacks. |

The fifth action plan (2021–2023) was developed during the middle of the Bolsonaro administration and at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. Civil society representatives cited numerous challenges during this cycle—from competing priorities, limited resources, restrictive normative actions, to strained relationships with government—with some feeling that OGP commitments helped maintain the open government agenda. The CGU’s role was crucial in managing these challenges by reinforcing practices of regular monitoring meetings and progress reporting for commitments. A civil society stakeholder pointed out that public servants’ dedication ensured the continuity of the OGP process under the administration. Altogether, these factors allowed the ATI agenda to progress. For example, the government and civil society co-created an interface that centralized access to environmental licensing that was previously only available via direct information requests.

In its sixth action plan (2023–2027), Brazil has committed to improve its culture of access to information and standardize compliance with the ATI Law. The creation of a national ATI network would serve as a collaborative platform that brings together federal, state, and municipal entities to ensure aligned implementation of the law across levels. The network would disseminate best practices to process requests, create opportunities to share successful experiences and innovative solutions, provide critical technical support especially to smaller municipalities, and offer capacity building and training for public servants.

ENHANCING OPEN DATA EFFORTS THROUGH OGPBrazil’s efforts in open data date back many years prior to joining OGP. Since 2004, Brazil’s Transparency Portal has enabled citizens to monitor and track the allocation of public funds, and has been used by media and watchdog groups to denounce wrongdoings. Currently, the portal publishes data in open formats on various financial transfers and expenditures, covering 18 integrated subjects and updating over 50 thousand records daily. |

Using OGP as a Platform to Nurture and Protect Policy

Throughout its 13 years of participation in OGP, Brazil’s six action plans have included 130 commitments. In some cases, the OGP platform has been used to foster growth in new policy areas while in other cases it has served as a space for resilience and continuity.

The development of commitments to ensure scientific research and data are publicly available (known as “open science”) demonstrates how organizations and institutions have used the OGP platform to build a community and nurture a policy area from specific actions toward the creation of a national policy. Brazil’s experience has shown that the results of environmental commitments sometimes take longer than the two-year action plan implementation cycle, but their inclusion in OGP action plans has ensured the topic remains on the policy agenda, even in difficult political contexts.

Advancing Open Science through the OGP Process

Although 95% of scientific research in Brazil is conducted by public universities and is financed by public agencies, limited access to scientific data has been a persistent challenge. The open science movement, focusing on open access to government-funded research in Brazil, dates back to the early 2000s. It allows scientific research to be validated and shared widely, further contributing to scientific advances for the benefit of society as a whole. Government stakeholders agree that the advancement of open science gained a new impetus through OGP.

Public research institutions, under the leadership of the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (EMBRAPA), joined the OGP co-creation process in 2017. The open science theme was incorporated into the fourth action plan (2018–2021), initiating actions to establish governance mechanisms for scientific data publication and to enhance the open data infrastructure for scientific research. It achieved major results, including the institutionalization of open scientific data practices and the launch of data repositories by several public institutions and universities. During the COVID-19 pandemic, EMBRAPA says these repositories played a crucial role in rapidly disseminating research findings.

Representatives from the Brazilian Institute of Information in Science and Technology (IBICT) highlight that the positive results from the fourth action plan generated interest among stakeholders to reintroduce the theme in the fifth action plan (2021–2023). The commitment, led by IBICT, proposed new mechanisms to evaluate and reward transparency measures in scientific research. Scientific evaluation, both in Brazil and internationally, relies on citation metrics linked to a system which favors journals that charge for access to articles. To change this, the commitment led to new guidelines that encourage open science, including in funding criteria, the Brazilian higher education evaluation system, citizen science, and scientific repositories. The commitment resulted in a pilot observatory to monitor and showcase the impact of open science practices.

These commitments have increased the number of open data repositories and encouraged Brazilian scientific journals to adopt transparent editorial processes and require data submission to open repositories. There are nearly 50 examples of library practices that support research development and citizen science. Additionally, government stakeholders said the commitment has strengthened the BR.CRIS system, which provides information on research such as authors, funders, research institutions, and results—all built on the now more openly available data.

The Ministry of Science, Technology, and Innovation (MCTI) leads the coordination of the open science commitment in Brazil’s sixth action plan (2023–2027). An EMBRAPA representative says it ambitiously aims to establish an open science policy and national strategy while also building on and expanding previous actions.

Open science commitments have evolved from foundational steps like opening scientific data to advancing a national policy and strategy. The actions undertaken in the commitments have built upon one another, with each plan selecting an appropriate coordinator. EMBRAPA led the fourth action plan’s commitment due to its expertise in open repositories and data governance, while IBICT contributed technical knowledge for developing new evaluation criteria and monitoring systems for open science. Currently, the MCTI leads the goal of establishing an open science policy. The open science group understands that to succeed, whoever leads must have agency and expertise in the decided actions.

OGP has been instrumental in advancing open science in Brazil according to representatives from EMBRAPA and IBICT. The platform helped mobilize nearly 36 stakeholders to pursue a common agenda collectively, provided a robust results-oriented methodology for focusing and monitoring actions, fostered a collaborative environment centered on co-creation, offered international validation, and attracted new stakeholders by showcasing clear results. Additionally, they say it has developed networks and a sense of ownership that extends beyond the OGP platform.

But the progress has not come without challenges. According to government representatives, these include coordinating a large group who have respective institutional responsibilities, addressing the mismatch between individual and institutional representation, ensuring ongoing civil society engagement during implementation, sensitizing stakeholders about the OGP methodology, and navigating a political context that has been at times less receptive to science-based initiatives.

A scientist at work in Florianópolis, Brazil (Photo credit: Lucas Vasques via Unsplash)

A scientist at work in Florianópolis, Brazil (Photo credit: Lucas Vasques via Unsplash)Advancing Environmental and Climate Actions through the OGP Process

Given its status as a major player in the global agribusiness sector and holder of 60% of the Amazon rainforest, environmental and climate issues are major topics of interest in Brazil. Open government reforms can help determine the true costs, impacts, and causes of environmental issues while ensuring adequate public oversight with the involvement of affected stakeholders to collaboratively discuss alternative and innovative approaches to development.

Civil society and government have repeatedly brought environmental themes into the OGP process in Brazil. Yet, while some environmental commitments have failed to meet expectations, their inclusion in OGP action plans has ensured it remains on the policy agenda even under challenging political circumstances. According to a representative from environmental CSO Imaflora, many environmental commitments have also shown more impactful results after the end of the respective action plan, which contrasts with the rapid and tangible changes that are often expected within the OGP timeframe.

Brazil’s second action plan (2013–2016) included a commitment to develop an online information panel to improve water access for communities affected by the historic droughts that began in 2014. This commitment was a step forward in fulfilling community desires for greater transparency in water resource management. Another commitment aimed to establish processes for consultations under International Labor Organization Convention 169 while safeguarding the rights of indigenous and tribal peoples to land, resources, and cultural integrity as well as facilitating their participation in decision-making, including in environmental protection and resource management.

The creation of the National Council for Indigenous Policy (CNPI) during implementation received mixed reviews. Indigenous representatives stated it was more limited than pre-existing engagement mechanisms. Opinions within the government varied from support for regularizing prior consultations to advocating for the use of existing and proposed platforms. Regardless, the CNPI has remained a space for indigenous people’s participation, helping to advance the environmental agenda through protection plans and actions to reduce illegal deforestation.

The third action plan (2016–2018) included a commitment to provide a space for dialogue between government and civil society to open environmental licensing, deforestation, and forest conservation datasets. It led to the publication of new datasets and planned releases in the Ministry of Environment’s Open Data Plan. According to an Imaflora representative, it started a discussion that led to the disclosure of key information to monitor illegal deforestation and was successful in opening information on timber production, which is an important economic sector.

The fourth action plan (2018–2021) included three environmental commitments. These concerns were even more pressing during the Bolsonaro administration, especially given the reported deterioration of environmental protection actions and the increase in deforestation activities.According to civil society representatives, the OGP action plan was one of the few spaces that remained to discuss the environmental agenda at the time.

These three commitments saw varying success. One commitment improved the user experience and data complexity of the National Water Resources Information System, successfully disseminating it as a citizen monitoring tool for water resources. Another commitment succeeded in improving information disclosure of the reparation process following the 2015 environmental disaster near the city of Mariana. However, it fell short in enabling affected citizens to monitor the process. Since then, the portal has continued to provide information and evolved into a more robust accountability tool that enables the monitoring of expenditures and progress across the 42 programs dedicated to the reparation process. The implementation of a third commitment to establish a transparency mechanism to evaluate actions and policies related to climate change was hindered by the political context and disagreements over which policies should be evaluated. Ultimately, civil society formally withdrew its participation in this commitment.

The fifth action plan (2021–2023) included three further commitments related to environmental transparency and civic participation and monitoring. One led to the successful co-creation of an implementation plan between the Brazilian Institute of the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA) and civil society to improve and ease access to specific environmental databases which then became an official ordinance to turn these actions into an institutional priority. Notably, it led to improved data to trace the origin of timber (known as the Document of Forest Origin), which has been a longstanding challenge. The second commitment significantly improved access to environmental licensing data which has resulted in increased opportunities to monitor human-driven environmental activities. IBAMA engaged civil society to inform the usability of the information and user-oriented improvements to the platform. Meanwhile, the third commitment on open agricultural data was a civil society priority but achieved only mixed results. Civil society noted that the Ministry of Agriculture was uncooperative in disclosing essential data, such as Animal Transport Data. In contrast, the ministry argued that sharing this database would violate Brazil’s General Personal Data Protection Law, and that its intended use was for sanitation monitoring rather than environmental oversight. According to EMBRAPA, although the commitment did not fully meet civil society’s expectations, it advanced the opening of databases, fostered important discussions within the OGP space, and inspired further transparency initiatives in agricultural data beyond the action plan.

The sixth action plan (2023–2027) does not contain any environmental commitment as relevant proposals did not receive enough support during the action plan co-creation process. An Imaflora representative explained that the Lula administration’s commitment to environmental issues made it less urgent to prioritize this theme within the current OGP action plan. Outside OGP, CSOs in Brazil continue to advocate for openness in tackling environmental issues, such as through the Escazú Agreement.

Civil society representatives emphasize that OGP has reduced the distance between civil society and government, facilitating further collaboration outside the action plan process. A notable distinction of the OGP action plan environment compared to other participatory spaces is that interactions are more horizontal than vertical, promoting a more equitable exchange of ideas and resources between civil society and public servants. Civil society representatives state that ongoing commitments have contributed to strengthening the culture of open data related to environmental information.

A bird in the Amazon rainforest, one of the most biodiverse places on Earth (Photo credit: Danilo Alvesd via Unsplash)

A bird in the Amazon rainforest, one of the most biodiverse places on Earth (Photo credit: Danilo Alvesd via Unsplash)Supporting Local Efforts to Embed Open Government

Since OGP’s inception, Brazil has used national action plans to spread open government to the state and local levels. To date, there have been 11 commitments addressing reforms at the local level in Brazil’s national OGP action plans.

Brazil’s second action plan committed states and municipalities to adopt open government principles in the application of major welfare programs and to foster an open data culture among state and municipal leaders. Among these early commitments, the Brazil Transparent program was one of the most successful. The CGU trained 10 thousand people on ATI implementation, and the program led to the creation of a transparency index by grading compliance with the ATI Law in municipalities and states. Over 1,600 municipalities (nearly a third of all municipalities) had joined the program by 2016. Brazil Transparent also served as a precursor to Time Brazil, which supports municipalities and states in enhancing transparency, integrity, and social participation. Government stakeholders said Time Brazil was seen as a key driver of open government at the local level and was recognized in the OECD’s open government review of Brazil as a key open government initiative.

The fourth action plan’s commitment to bridge gaps in the implementation of the ATI request system at the municipal level was also successful. The newly created one-stop shop Fala.BR platform improved the process to make an ATI request, provide feedback, and engage with public services. The system was widely adopted across state and local entities. The CGU has developed support materials and training to enhance its effectiveness and empower public managers to better handle citizen interactions.

In what was a first, Brazil’s fifth action plan designated a local level actor to coordinate a commitment that, with support from civil society and the Senate, resulted in improved guidelines, practices, and awareness relating to accessibility to legislative processes for individuals with disabilities. On the other hand, a commitment to implement standards for system and data integration of the National Health Surveillance System at all levels of government failed to involve municipal and state governments in validating and endorsing the proposed changes.

The sixth action plan includes commitments to promote a culture of access to information, enhance ATI Law at the municipal level, and develop a detailed database of affirmative action policies.

Advancing Open Government at the Local Level

OGP Local has been another avenue to advance open government at the local level in Brazil. OGP Local aims to harness the innovation and momentum of local governments and civil society to come together to make their governments more open, inclusive, and responsive to citizens by co-creating their own action plan. Six different municipal and state governments participate in OGP Local with their own open government action plans.

In 2016, São Paulo became the first Brazilian local government to join the OGP Local program. Following São Paulo and demonstrating their own commitment to open government, Osasco municipality and Santa Catarina state joined in 2020, followed by Contagem municipality in 2022, and then Goiás state, which surrounds Brasília, as well as Vitória da Conquista in Bahía state in 2024.

There are various factors that have influenced local governments in Brazil to participate in OGP Local. City officials in Osasco realized that their existing efforts aligned with open government principles after joining the 2019 Open Government Meeting in Brasília. Developing its OGP action plan during the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the benefits of online citizen participation in Osasco. In Contagem, the need to rethink citizen engagement strategies after the pandemic was factored into its decision to join OGP. Seeing it as an opportunity to address gaps in its open government practices, Contagem’s interest was also triggered by the legal requirements of Brazil’s ATI and General Data Protection Laws.

Furthermore, local government representatives said that association with a global platform like OGP has motivated progress by providing legitimacy and a sense of accountability. In Vitória da Conquista, local officials noted that OGP’s international visibility helped keep momentum behind open government goals.

Senior political prioritization has also helped advance the open government agenda despite the challenge of securing internal buy-in from government administrators who remain unfamiliar with concepts like transparency, public participation, and accountability. In Santa Catarina, the then-governor established the State Comptroller’s Office and introduced open government as an initiative as a result of crowdsourcing and deliberation exercises seeking to strengthen the policy agenda. In Osasco, open government has benefitted from strong leadership of the mayor. The city’s low ranking in CGU’s transparency assessment was also a wake-up call, according to government representatives. Nevertheless, the implementation of open government initiatives relies heavily on department heads who are often resistant or slow to act. In São Paulo, public officials have found that moving the coordination role from the International Relations Secretary to the Civil House, closer to the mayor, has facilitated the co-creation and implementation of their open government reforms.

Local Networks and Peer Exchange

Local stakeholders from government and civil society have used the OGP platform for networking and knowledge exchange. For example, São Paulo and the Province of Córdoba, Argentina, have led conversations in a Local Circle about the 2030 Agenda and the territorialization of the SDGs, inspiring other localities to address such issues with an open government perspective. Local stakeholders who met at the America Abierta OGP Summit in 2022 began an informal network to share best practices and innovative approaches. Launched officially in 2024 as the Brazilian Open Government Network, this broad community comprises OGP Local members, academia, civil society, and CGU. Together, they committed to advance open government principles across Brazil. In Vitória da Conquista, the network helped the municipality recognize the benefits of joining OGP Local, which aligned well with open government initiatives already being carried out. This external support has empowered city officials to engage more effectively with citizens and deepen their commitment to open governance, ensuring these principles were embedded into local policies and practices. The network’s diverse and inclusive nature has also enabled open government practices to spread outside the OGP platform—such as in Mogi das Cruzes in São Paulo—and brought other leading actors in transparency—such as Espírito Santo state—to share their best practices.

Local stakeholders feel that OGP needs to broaden out beyond urban centers to include regions with rural and multicultural characteristics in Brazil. The involvement of local legislatures and judiciaries is also necessary, as local open government initiatives tend to be overly concentrated in the executive branch. By fostering collaboration and learning across these networks, more local administrations can benefit from shared experiences and resources.

OGP Local points of contact from São Paulo, Osasco, and Santa Catarina meet for the first time in person during OGP’s 2022 Open Gov Week (Photo credit: OGP Local member Santa Catarina)

OGP Local points of contact from São Paulo, Osasco, and Santa Catarina meet for the first time in person during OGP’s 2022 Open Gov Week (Photo credit: OGP Local member Santa Catarina)The Benefits of Institutionalizing Local Open Government

Several municipality representatives stated that establishing bodies, passing laws, and issuing norms has helped make open government a permanent fixture in the public administration. The decentralized nature of Brazil’s governance structures means that institutionalizing open government through local coordinating offices, oversight bodies and practices has helped advance efforts, even while there is backsliding at the federal level. For example, the local Department of Open Government in Osasco has enabled the local government to implement its open government agenda. Similarly, São Paulo institutionalized a Coordinating Body for Open Government, which has strengthened the city’s open government efforts continuously despite political changes nationally and locally. In Vitória da Conquista, the legal framework backing the “Governing with People” initiative was instrumental in ensuring its persistence even after administrative changes.

Institutionalizing practices has also helped to enhance positive outcomes of open government. For example, the creation of the Transparency Coordinator Office, the Open Government Committee multi-stakeholder forum, and the Council of Public Services Users helped Vitória da Conquista move towards greater engagement. There has been a noticeable shift in the way civil society engages with the government, particularly through participatory councils. Citizens now come prepared to contribute rather than air grievances, reflecting a growing trust in collective construction efforts. Furthermore, there is a continued and growing conceptual understanding of open government among local government officials who are more enthused about the implementation of participatory, transparency, and accountability measures.

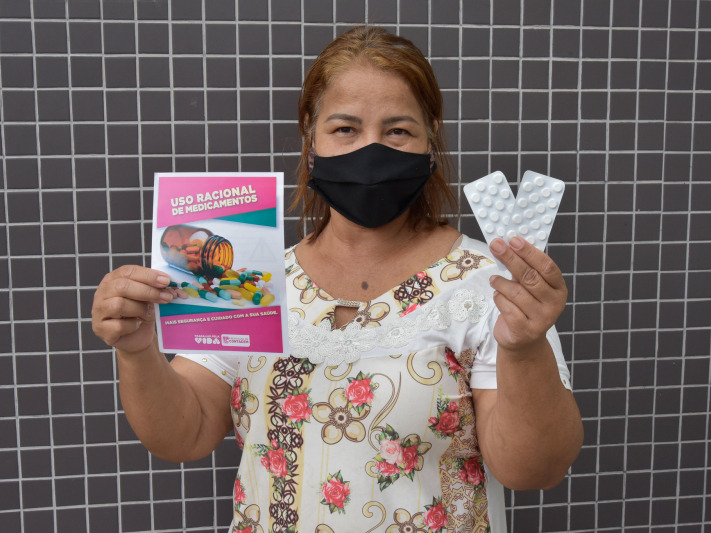

In Contagem, the OGP process has encouraged the adoption of more inclusive and accessible practices in public bodies such as the Attorney General’s Office, which is traditionally perceived as closed. It has also translated into developing legal frameworks that include OGP principles and open data specifications, such as the Contagem Policy for Citizen Participation. The city also won an Open Government Award for its Aqui tem remédio platform that tracks medicine availability in municipal pharmacies. According to local officials, the city’s involvement with OGP has enhanced trust between the government and citizens who now feel they can communicate effectively with government channels such as the ombudsman and municipal councils. Clear institutional communication pathways have also fostered trust with the media and improved civil society engagement.

In contrast, according to an academic, government shifts resulting from elections have caused open government to be deprioritized in Santa Catarina, having yet to submit a second action OGP Local plan. The position overseeing the initiative at the Comptroller’s Office has recently been filled.

Photo from Contagem’s Aqui tem remédio platform and campaign to track medicine availability in local pharmacies (Photo credit: OGP Local Member Contagem, Brazil)

Photo from Contagem’s Aqui tem remédio platform and campaign to track medicine availability in local pharmacies (Photo credit: OGP Local Member Contagem, Brazil)Engaging the Public and Civil Society

Public and civil society engagement has been another crucial factor in advancing and sustaining local open government initiatives. Local government representatives recognize that while legislative and institutional reforms are important, the continuous strengthening of civil society is vital for long-term success. Contagem, Vitória da Conquista, Osasco, and São Paulo have seen increased participation from civil society through councils and open government committees, with the local civil society groups playing an instrumental role in the creation of the Brazilian Open Government Network. In Santa Catarina, interest from the academic community has kept local actors engaged in open government both within and outside the state.

However, local institutions need to work towards addressing the limited public understanding of open government and the possibilities it provides for better governance. Despite the success of the “Osasco Aberto” branding and publication of informational booklets, an Osasco government representative recognized that participation remains low due to limited public knowledge about open government initiatives and false perception that the commitments adopt a top-down approach or technical actions far removed from local and pressing issues.

VITÓRIA DA CONQUISTA: Vitória da Conquista’s anti-corruption law expanded the responsibilities of the Secretariat of Transparency, Control, and Prevention of Corruption. It also created new oversight bodies, including the Municipal Transparency and Integrity System which includes councils and committees to prevent corruption and improve public service governance. Local government officials see the institutionalization of these bodies and responsibilities as giving the city authorities a clear mandate to fight and prevent corruption. It is currently developing its first OGP action plan. |

Triumphs, Challenges, and the Road Ahead

As a founding member and incoming co-chair of OGP, Brazil has been a leader in the partnership since its inception. It has developed six national action plans with 130 commitments to advance transparency, participation, and accountability. One in five of these commitments have seen strong early results. Significant achievements include the enactment and continued implementation of the Access to Information Law as well as the Fala.BR and Participa+ Brasil platforms, which have empowered millions of citizens to engage directly in policy making.

OGP has provided Brazil with an international framework that brings dispersed open government initiatives together into a cohesive effort to achieve progress, even in politically challenging times. When civic space narrowed during the Bolsonaro administration, the OGP platform remained an avenue for maintaining environmental and transparency commitments. The OGP process has also supported innovation in municipalities like Contagem, São Paulo, and the state of Santa Catarina, where open government principles are now embedded into local governance.

Despite progress in opening government, challenges persist. Fragmented efforts, regional disparities, and limited capacity remain barriers. The commitments and increasing diversity of civil society in the OGP process have helped to expand the scope of open government initiatives and add pressure for implementing open government reforms. The involvement of civil society and institutionalization of open government reforms will be key to addressing challenges and ensuring long-term success towards greater open government. Under the renewed interest of the Lula administration, institutional initiatives like the Open Government Strategy, and its upcoming co-chair position in the OGP Steering Committee, Brazil has signaled that its open government journey is embarking on a new chapter.

Sunrise over Pedra da Gavea, Rio de Janeiro (Photo credit: Noah Angelo via Unsplash)

Sunrise over Pedra da Gavea, Rio de Janeiro (Photo credit: Noah Angelo via Unsplash)Appendix

About this report

As the Open Government Partnership implements its 2023–2028 Strategy, changes in approaches, ways of working, and learning are key in achieving the organization’s strategic goals. The Independent Reporting Mechanism (IRM) continues to contribute towards this through its vital role in producing and disseminating evidence-based research.

The scope of IRM reports have focused on the activities during an action plan cycle. This research has created useful data and provided valuable information to the Partnership and open government community. However, since the analysis is largely restricted to developments within an action plan cycle, IRM reports are less able to answer some of the longer-term questions which OGP wishes to learn from, as part of this new strategy.

In 2024, the IRM committed to producing a report reflecting on Brazil’s 13 years of participation in OGP. This Open Government Journey report explores Brazil’s open government evolution and achievements across action plans, government, and civil society to distill learnings from the work of reformers, the OGP Support Unit, and partners.

Methodology

This report was written by Andreas Pavlou, Juan Collazos, and Pedro Espaillat.

It was reviewed by Caro Cornejo, Christina Socci, Clora Romo, Jose Maria Marin, Jose Perez, Munyema Hasan, Rocio Moreno Lopez, Shreya Basu, and Tinatin Ninua. It was also reviewed by key Brazilian stakeholders in government, civil society, and academia. Many thanks go out to others who have contributed towards the report.

To produce this report, the IRM interviewed 31 individuals from federal and local governments, civil society, and academia in Brazil. These included interviews with: Bianca Amaro (Brazilian Institute of Information in Science and Technology, IBICT), Bruno Schimitt Morassutti (Fiquem Sabendo), Carolina Pereira Matias da Silva (Osasco City Hall), Claudia Taya (Office of the Comptroller General), Danielle Abud (Federal Senate), Danielle Bello (Open Knowledge Brazil), Edgar Maturana (Contagem City Hall), Fabro Steibel (Instituto de Tecnologia & Sociedade do Rio de Janeiro), Felipe Tannus (Osasco City Hall), Gregory Michener (Fundação Getúlio Vargas), Humberto Formiga (Federal Senate), Izabela Correa (Office of the Comptroller General, Katia Cilene Brembatti (Abraji), Maira Souza Rodrigues Povoa (Office of the Comptroller General), Maria Dominguez (Transparency International), Maria Valdenia Santos de Souza (Office of the Comptroller General), Marina Atoji (Transparency Brazil), Mateus Nascimento Novais (Vitoria da Conquista City Hall), Midian Borges dos Reis Vieira (Vitoria da Conquista City Hall), Milena Coimbra (Open Knowledge Brazil), Patricia Marques (São Paulo City Hall), Paula Chies Schommer (University of the State of Santa Catarina), Pepe Tonin (Office of the Comptroller General), Priscila Sena (IBICT), Priscilla Ruas (Office of the Comptroller General), Raquel Pereira (Office of the Comptroller General), Ricardo Meirelle (Federal Senate), Roberta Delgiudice (World Resource Institute – Brazil), Sarah Campos (Contagem City Hall), Washington de Caravalho (IBICT).

Previous IRM products and reports covering all six of Brazil’s action plans were also used, as well as information sourced from desk research.

Source:

Source: