Ecuador Results Report 2019-2022

- Action Plan: Ecuador Action Plan 2019-2022

- Dates Under Review: 2019-2022

- Report Publication Year: 2023

The implementation of Ecuador’s first action planAction plans are at the core of a government’s participation in OGP. They are the product of a co-creation process in which government and civil society jointly develop commitments to open governmen... generated important early resultsEarly results refer to concrete changes in government practice related to transparency, citizen participation, and/or public accountability as a result of a commitment’s implementation. OGP’s Inde... More on key issues, such as transparencyAccording to OGP’s Articles of Governance, transparency occurs when “government-held information (including on activities and decisions) is open, comprehensive, timely, freely available to the pub... More in public procurementTransparency in the procurement process can help combat corruption and waste that plagues a significant portion of public procurement budgets globally. Technical specifications: Commitments that aim t... More and the protection of women and the LGBTI+ community. Civil society and academia had a significant role in the process given the participation strategy in place, although it has to reach the territorial level. A challenge for the next plan is that the formulation should focus both on creating public policy instruments and tools and their implementation.

Early Results:

Early Results:

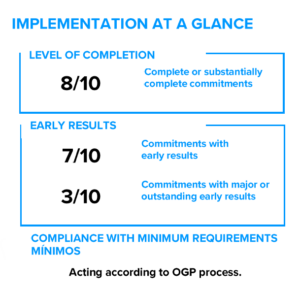

By the end of the implementation period[1], of the ten commitments included in Ecuador’s first action plan four achieved marginal early results, two outstanding, and one significant.

The main results achieved include updating the open dataBy opening up data and making it sharable and reusable, governments can enable informed debate, better decision making, and the development of innovative new services. Technical specifications: Polici... portal with a significant increase in the number of data sets available and the institutions that publish them. Concerning public procurement, the update of the open data portal allowed access to timely information on the management of emergency purchases during the COVID-19 pandemic, a key point considering the corruption cases registered in the country.

On the other hand, in terms of prevention and eradication of violence against women and people from the LGBTI+ community, the process generated two national plans with concrete actions in favor of these groups, for which State institutions have clear responsibilities and a mechanism to monitor compliance. In response to the need to have the necessary institutional framework to serve these groups, and to complement the efforts of this commitmentOGP commitments are promises for reform co-created by governments and civil society and submitted as part of an action plan. Commitments typically include a description of the problem, concrete action..., the government created the Undersecretariat of Diversities. The active participation of government entities, civil society organizations (CSO) and academia, the support of international cooperation, and citizen participationAccording to OGP’s Articles of Governance, citizen participation occurs when “governments seek to mobilize citizens to engage in public debate, provide input, and make contributions that lead to m... More spaces, were common factors that allowed the achievement of these results.

The commitment to implement the Escazú Agreement, identified as promising, did not achieve notable early results during implementation. Although a regulatory analysis and a proposal for an inter-institutional participation mechanism were developed, the IRM was unable to verify that actions were implemented to modify the current regulations or that the Inter-institutional Roundtable for Environmental Democracy began to work. This would have meant a change in government practice. However, the IRM includes an analysis of this commitment in the Implementation and Early Results section given the quality of the process and the relevanceAccording to the OGP Articles of Governance, OGP commitments should include a clear open government lens. Specifically, they should advance at least one of the OGP values: transparency, citizen partic... of the subject at a national and international level.

CompletionImplementers must follow through on their commitments for them to achieve impact. For each commitment, OGP’s Independent Reporting Mechanism (IRM) evaluates the degree to which the activities outlin... More:

This action plan organized its commitments into four areas: open data, capacity buildingEnhancing the skills, abilities, and processes of public servants, civil society, and citizens is essential to achieving long-lasting results in opening government. Technical specifications: Set of ac... for transparency, citizen empowerment and public innovation. Of the ten initiatives, only two reached a limited level of implementation, while the rest were fully implemented or achieved substantial level of completion. Financing and technical assistance from international cooperation and the support of counterpart civil society organizations, allowed most of the initiatives to be implemented as scheduled.

The commitment regarding the implementation of the extractive industry standards achieved a limited level of completion due, in part, to the delay in managing the resources to finance the implementation of the proposed roadmap. While for commitment 6, related to capacities to promote access to information, only the elaboration of a toolbox and the methodological definition of the pilot projects were achieved, but not implemented. At the time of writing this report, the country is also approving reforms to the Organic Law on Transparency and Access to Public Information, key to this and other commitments included in this plan.

Participation and Co-creation:

The Open Government Directorate of the Undersecretary of Open Government is responsible for the Open Government Partnership (OGP) process in the country. The Core Group, which brings together organizations from civil society, academia and the government coordinated, accompanied and monitored the co-creation and implementation of the action plan[2].

The co-creation methodology generated an iterative dialogue. To this end, different spaces were set up to present and validate proposals from citizens and organized civil society. For the implementation process, the responsible institutions and counterpart entities (CSOs and universities) signed agreements that established responsibilities for the government’s entity in charge of the commitment and its counterpart from civil society or academia, designating points of contacts for each case. Under these responsibilities, some organizations provided specific technical assistance to government institutions for implementation, including technical training and support to develop information platforms[3]. Most international cooperation funds received for the process, mainly German and American, were channeled through these organizations. Participation, however, was affected by the COVID-19 pandemic due to the prioritization of emergency care and the challenges of sustaining interest due to virtuality. Similarly, the climate of mistrust generated by citizen protests led by indigenous groups affected the process[4].

Implementation in Context:

The action plan’s implementation coincided with the pandemic and the electionsImproving transparency in elections and maintaining the independence of electoral commissions is vital for promoting trust in the electoral system, preventing electoral fraud, and upholding the democr... More, which the current president, Guillermo Lasso, won. The restrictions on mobility forced the rescheduling of the plan’s activities, in accordance with the OGP resolution, so they had to be executed virtually. As indicated above, this impacted the number of participant organizations in the implementation, especially those that work at the territorial level.

On the other hand, the approaches made by civil society organizations and academia, part of the Core Group, with the then presidential candidate Guillermo Lasso, made it possible to obtain the necessary early political support to ensure the continuity of the process. The work of the organizations and the Open Government Directorate was also important during the transition, since it allowed the new authorities to become involved in the implementation of the commitments.

Towards the end of the implementation period, the country experienced a series of social conflicts due to strikes led by indigenous organizations. The government’s response to these demonstrations has generated reactions at the international level. At the national level it has undermined the confidence of many organizations to get involved in working with government institutions.

[1] This report covers the implementation of activities until the end of the implementation process on August 31, 2022.

[2] The Open Government Core Group of Ecuador is made up of 12 public, academic, and civil society entities. Participating for the public sector are the Presidency of the Republic, the Technical Planning Secretariat “Planifica Ecuador” (STPE), the Ministry of Telecommunications and Information Society (MINTEL), the Ministry of Production, Foreign Trade, Investment and Fisheries (MPCEIP) and the Ombudsman. Civil society is represented by the Development and Citizenship Foundation (FCD), the Fundación de Ayuda por Internet (FUNDAPI), the Foundation for the Advancement of Reforms and Opportunities (FARO Group), and the Esquel Foundation. Finally, the academic sector is represented by the Institute of Higher National Studies (IAEN), the University of the Hemispheres (UHemisferios), and the Private Technical University of Loja (UTPL).

[3] Datalat, Fundación de Ayuda por Internet (FUNDAPI), among others.

[4] BBC Mundo, Protests in Ecuador: Three keys to understanding the demonstrations of indigenous groups and the state of emergency decreed by the government, available here: https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias-america-latina-61854940

Leave a Reply