Open Response, Open Recovery

Respuesta abierta, recuperación abierta

Réponse ouverte, Récupération ouverte

Open Response, Open Recovery

Building Trust as the Antidote to COVID-19

Executive Summary The COVID-19 pandemic has compelled governments and citizens alike to take unprecedented, mitigating actions. In their shared struggle, mutual trust between government and citizenry can be key for successful, mutually-reinforcing response and recovery. “Open Response, Open Recovery” can build mutual trust: transparent and accurate disclosure and directives by government empowers citizens to take responsible, mitigating action to curb contagion; citizens empower governments to unleash emergency powers, mobilize massive medical care and launch big stimulus packages, while governments act with integrity, open themselves to public scrutiny and roll back emergency powers after the pandemic. In this review, we examine concrete and practical ways in which openness — through transparencyAccording to OGP’s Articles of Governance, transparency occurs when “government-held information (including on activities and decisions) is open, comprehensive, timely, freely available to the pub... More, citizen engagement and oversight — can help tackle three stages of the pandemic response, recovery and longer-term reform. Our review is anchored in nearly a decade of experience with the Open Government PartnershipThe Open Government Partnership (OGP) is a multi-stakeholder initiative focused on improving government transparency, ensuring opportunities for citizen participation in public matters, and strengthen... More (OGP), including over 4,000 open government reforms co-created by government reformers and civil society across 78 countries, as well as over 200 approaches crowdsourced in the ongoing COVID-19 response. Open Response:

Open Recovery:

Open Reform Over the Long-Term: As societies recover, they need to re-empower citizens by rolling back restrictions on civic freedoms and new surveillance mechanisms that were instituted to curb contagion. To build resilience in responding to the next disaster, they need to protect whistleblowers, scientists, and independent media. As we move through the phases of this pandemic, we will share real-time, practical learnings from ongoing responses. This call-to-action provides a list of where stakeholders can start. We hope you will join us in shaping a new governance model that places citizens at the heart of government, that builds trust – underpinned by openness – as the most powerful antidote to COVID-19.

|

Introduction

Tackling a social calamity is not like fighting a war which works best when a leader can use top-down power to order everyone to do what the leader wants — with no need for consultation. In contrast, what is needed for dealing with a social calamity is participatory governance and alert public discussion.

The coronavirus pandemic has caused untold suffering in the lives of citizens across the world, causing loss of loved ones, loss of jobs, and loss of peace of mind. While essential workers are valiantly providing vital services – from health care to food supplies – on the frontlines, citizens also face the onus of taking life-saving mitigating actions, from home-quarantines and caring for their ill to making ends meet amidst layoffs. At the same time, the vital role of government in protecting and supporting its citizens has never been more compelling. Across North and South, across developed and developing countries, across ideological divides of left and right, there is consensus on the imperative for strong, decisive government action to stem contagion, mobilize massive medical treatment for the infected, protect the most vulnerable, and stimulate economic recovery to revive jobs.

But how are governments engaging and empowering citizens who they have a responsibility to protect and help, and how are citizens relating to their government in the spirit of mutual trust? How can governments and citizens work together in this shared struggle?

Globally we are witnessing a wide array of approaches that governments are adopting in this pandemic to control or empower their citizens – from totalitarian surveillance and control in China to laissez-faire reliance in Sweden on an informed citizenry to take responsible action. These approaches reflect a wide diversity of political regimes and different levels of civic engagement, social cohesion, and technological penetration. The effectiveness of these approaches will likely depend not on the type of regime as neither autocracies nor democracies have been unambiguously successful even in these early stages. Rather, effectiveness will ultimately depend on a range of underlying factors such as state capacity, including the strength of healthcare systems and the degree to which citizens trust the state and their leaders.

Across these pandemic responses, citizens represent not just passive subjects or beneficiaries of governmental action and control, but vital and active agents, partners, and allies in this shared struggle – taking responsible action to protect themselves and others to curb contagion, shaping and overseeing governmental recovery efforts to follow. Key to successful response and recovery lies in both catalyzing this widespread desire among citizens to be useful contributors and building trust in government action. Prior to the pandemic, citizen trust in institutions had plummeted to historically low levels in many countries, which risks undermining the potential of citizen engagement in the response and recovery. Open government approaches – “Open Response, Open Recovery” – can help build trust and empower citizens. It can create an environment in which: citizens trust and respond to transparent, trustworthy, and proactive disclosure and directives from government to stem contagion, and government trusts citizens to take responsible action; and, citizens empower governments to unleash emergency powers, big stimulus packages, and far-reaching safety nets, while governments act responsibly with integrity, open themselves to public scrutiny, and roll back emergency powers after the pandemic has subsided.

Trust – underpinned by openness – must be the basis of the new social compact necessary to drive a lasting and effective response to COVID-19. It can help tilt a longer-term shift to a governance model with citizens more at the center.

In this context, we will review early COVID-19 responses as well as lessons from past interventions to examine how open government approaches can build trust and enhance the effectiveness of pandemic response and recovery. The Open Government Partnership (OGP) has already crowdsourced over 200 open government approaches in the ongoing COVID-19 response from our community of 78 countries, local governments and thousands of civil society organizations. Additionally, we considered relevant lessons from 4,000 commitments over the past nine years across over 250 OGP action plans co-created by government and civil society reformers to make governments more open, participatory, and responsive to its citizens.

In the following series, we examine how open government approaches – combining government transparency and citizen participationAccording to OGP’s Articles of Governance, citizen participation occurs when “governments seek to mobilize citizens to engage in public debate, provide input, and make contributions that lead to m... More and oversight – can help tackle three different stages or components of the pandemic response and recovery:

- Open Response: curbing contagion, scaling medical treatments and care, providing safety nets to the vulnerable

- Open Recovery: advancing economic stimulus and recovery, strengthening health systems, enhancing transparency and accountability of aid flows

- Open Reform over the long-term: reforming institutions and re-empowering citizens by rolling back state surveillance and restoring civic freedoms and independent oversight

OPEN RESPONSE

Curbing Contagion: Empowering Citizens with Proactive, Accurate Information

Even in the early stages of the virus’ global spread, we have seen the devastating human cost of failures in government transparency and early action. We have seen some governments downplay or hide the seriousness of the pandemic, delaying disclosure of risks and threats to citizens, jeopardizing citizens’ lives that could be saved with proactive disclosure and early actions.

In China, Iran, and the U.S., the initial period of political denial allowed the virus to spread unchecked. In China, those who attempted to blow the whistle early were threatened and critical information flows to the public were blocked. In contrast, governments like South Korea and Taiwan have taken the opposite approach – of proactive, clear, transparent, reliable information to empower citizens to take mitigating actions.

These diversity of approaches and results reflect different configurations of mutual trust between state and society and different degrees to which citizens have been empowered.

For example, in late January after its initial failure to curb contagion and inform the public, China unleashed massive state authority to impose lockdowns and deploy surveillance tools on its citizens, including monitoring people’s smartphones, using hundreds of millions of face-recognizing cameras, and obliging people to report their body temperature. At the same time, the state also marshalled huge numbers of citizen volunteers and healthcare volunteers.

In South Korea, the government’s success is largely anchored in extensive testing which was used for isolation and widespread contact tracing to break chains of transmission. But South Korea also relied heavily on transparency, citizen engagement, honest reporting and the willing cooperation of a trusting public. Participation was secured through openness and transparency, including daily public briefings and an extensive information awareness campaign aimed at effective social distancing.

Taiwan has managed to maintain remarkably low levels of infections and deaths not through top-down control, but through government transparency, which built public trust and empowered social coordination. For example, through the Face Mask Map, the government disseminated real-time, location-specific data to the public on mask availability, empowering citizens to collaborate and reallocate rations through trades and donations to those who most needed them.

While these approaches are being deployed in real-time now in response to a unique pandemic, there is precedent we can draw upon on how openness and transparency can save lives. For example, in 2001 in the UK, a public inquiry found that the mortality rates of babies undergoing heart surgery at the Bristol Royal Infirmary were double that of similar procedures performed elsewhere. Following the inquiry, heart surgeons across the National Health Service started publishing data on mortality rates from heart surgeries so people could make better informed choices. As a result, the death rates of babies undergoing heart operations dropped dramatically by 33 percent. Empowering citizens with proactive and accurate disclosure of information can save lives.

In our crowdsourcing of the ongoing COVID-19 response in OGP countries, we see governments making efforts at clear, accurate, and transparent public communications to inform, educate, and partner with the public, anchored in robust scientific evidence and expertise. Illustrative examples that OGP stakeholders are reporting include:

- Dashboards with real-time data on COVID-19 cases on infections, deaths, location (Argentina, Canada, Côte d’Ivoire, Italy, Jordan, Peru, South Africa, Tunisia)

- Accurate and open daily press briefings to inform the public and combat disinformation (Singapore, South Korea)

- Whatsapp and Facebook Chatbots to answer frequently asked questions related to the pandemic (Buenos Aires – Argentina, Morocco, Ukraine)

- Virtual maps to allow the analysis of COVID-19 data, including quarantine places, number of sick and recovered persons, medical staff in each municipality (Lithuania)

Scaling Medical Treatments and Care: Mobilizing Civic Engagement and Oversight

Scaling medical treatment and care for an exponentially growing number of infected patients lies at the core of the societal challenge. The pandemic is posing an excruciating strain on the health systems across nations. We are seeing two areas where open government approaches can help: (i) mobilizing community assistance for care; and (ii) making emergency medical procurement public and open.

Mobilizing community assistance for medical care: Across countries, brave but overstretched doctors, nurses, therapists, and other frontline responders battle selflessly to care for patients. The pandemic has unleashed a new sense of community support, often facilitated by technology and apps. In early, ongoing COVID-19 responses crowdsourced from the OGP community, we see various open platforms to mobilize community assistance for healthcare workers and the vulnerable. Illustrative examples that OGP stakeholders are reporting include:

- App and open source platform for doctors and hospitals to monitor remotely at-home patients with suspected or actual infection (France, Italy)

- Platform to support healthcare workers with day care of their children (France)

- Volunteer platforms to serve the elderly who are ill (Bulgaria, Georgia)

- Country hackathons to mobilize critical workers, community care, and civic-tech innovations (Colombia, Estonia, Germany, Latvia)

- Worldwide crowdsourcing of solutions to address the diminishing stock of medical equipment through Open Source COVID-19 Medical Supplies (global Facebook group)

Making emergency medical procurement public and open: Procurement has become a life or death issue in many countries’ response to the coronavirus pandemic. Shortages of personal protective equipment for frontline workers, ventilators, and testing capacity have hampered the response. Governments rushing to procure these vital resources, forgoing normal safeguards used in procurement contracts, can lead to bid rigging, kickbacks, and counterfeit supplies. For instance in 2010, the Global Fund paid millions of dollars to procure 6 million insecticide-treated nets against malaria in Burkina Faso, but nearly 2 million nets turned out to be counterfeit.

To tackle these challenges as governments scramble to procure emergency supplies quickly, they must make these procedures public and open to maintain public trust. For example, Ukraine’s anti-corruption reforms oblige all emergency contracts to be published in full and shared as open data. Civil society has developed a business intelligence tool to monitor medical procurement and emergency spending. Now they can track price differences for COVID-19 tests and other critical medical supplies to ensure that authorities are committed to filling treatment centers, not private pockets. Civil society is serving as a valuable ally in ensuring resources are used for their intended purpose, even while some elements within government are accused of malpractice.

In Latin America, Transparency International has convened a taskforce from 13 countries to identify risks in emergency public procurementTransparency in the procurement process can help combat corruption and waste that plagues a significant portion of public procurement budgets globally. Technical specifications: Commitments that aim t... More in response to COVID-19 – opacity, hidden contracts, overpricing, collusion, and lack of competition – and measures to mitigate them.

Providing Safety Nets for the Vulnerable: Including and Empowering the Excluded

The economic shutdown related to COVID-19 has devastated the lives of the poor and vulnerable who are least able to weather the shock. Already vulnerable groups are now losing their jobs without money to survive beyond the next few days. In India, the biggest lockdown in history of 1.3 billion people has left many millions of migrant workers unemployed and stranded in megacities, forced to take risky, long journeys back to their remote villages. For such vulnerable groups, poverty and hunger risk killing them before COVID-19 does.

In response, governments are already putting in place emergency measures to provide safety nets – from feeding programs and payroll subsidies to unemployment insurance. Illustrative examples that OGP stakeholders are reporting include:

- Converting state-issued IDs into debit card to provide basic support for medicines and groceries for the vulnerable (Panama)

- Simplified application forms for unemployed workers affected by the shutdown (Ireland)

- Creation of a special fund to help families in need (Lithuania)

- Citizen-driven voluntary committees to deliver food to vulnerable groups (Jordan)

A central priority must be to ensure transparency and civic oversight of these programs to ensure that they actually reach people in need. Examples from earlier OGP commitments include:

- Publication of budget allocation and results of targeted poverty reduction programs, with provisions for citizens to monitor and request information (Indonesia)

- Citizen participation and monitoring of the National Program for Poverty Reduction, including through social audits and citizen feedback mechanisms (Paraguay)

- Participatory budgeting for local poverty action plans in 595 municipalities (Philippines)

- Public dissemination of more than 1,600 indicators on welfare programs to allow journalists and citizens to monitor progress (Uruguay)

- Homelessness mapping systems to crowdsource inputs from the homeless and impacted communities on quality of services (City of Austin, United States)

Efforts to protect the vulnerable during the pandemic must include preserving open public discussion and an independent media as vital oversight mechanisms to amplify the plight of those most at risk. As Amartya Sen notes, building on his path-breaking work on how famines were averted in post-independence India, “even though only a minority may actually face the deprivation of a famine, a listening majority, informed by public discussion and a free press can make a government responsive.”

Any agenda supporting those left vulnerable by COVID-19 must not be limited to the economically disadvantaged, but also those socially impacted. For instance, one devastating impact of COVID-19 shelter-in-place orders is a significant rise in family and domestic partner violence around the world, which disproportionately impacts women. Stakeholders can draw upon past OGP commitments to enhance services for survivors of domestic violence, such as Ecuador collecting data on the prevention and eradication of violence against women and genderOGP participating governments are bringing gender perspectives to popular policy areas, ensuring diversity in participatory processes, and specifically targeting gender gaps in policies to address gov... More communities.

OPEN RECOVERY

Transparency & Accountability in Stimulus Packages

The pandemic will likely cause a significant global depression, which will inevitably require a massive stimulus to revive economies. Speed and responsiveness appropriately take center stage in jumpstarting recovery. However, transparency and public oversight of stimulus packages are key to ensuring that resources are put to good use and citizens’ trust in government is sustained. In practice this means that internal control mechanisms in public spending may be made more flexible, while audit trails are kept and public funds are audited. But this also requires transparency in terms of who gets the bailouts and subsidies, how the decisions were made, and whether the money is being used to reward the political elite or contributors to political campaigns. Stimulus and recovery programs must also address ongoing inequality challenges which have been exacerbated under COVID-19, such as inequities in those who are tested and those who are not, in the wealthy retreating into their homes while workers who don’t get paid sick leave deliver their food, or in the children from lower-income households struggling to connect to online digital classrooms so they may learn with the rest of their peers, among many others.

In designing stimulus packages to respond to these considerations, stakeholders can draw upon lessons from two sets of experiences in OGP: an accumulated body of core open government reforms and specific experience from past OGP commitments on stimulus packages and disaster-relief programs in particular.

Turning first to integrating core open government practices from past OGP commitments in the massive fiscal spending programs and the award of subsidies and bailouts:

- To sustain citizen trust, it is vital for the award of procurement contracts financed by massive stimulus packages to follow open contracting practices. For instance, to tackle the capture of public procurement by oligarchs, reformers in Ukraine built two online platforms (ProZorro and DoZorro) wherein all contracts are now disclosed in open data standards so citizens can search them and, importantly, report violations. In just two years, citizens cited more than 14,000 violations, resulting in $1 billion in government savings, 82 percent of entrepreneurs reporting reduced corruption, and a 50 percent increase in businesses bidding for public contracts. Seventy OGP governments have committed to open contracts.

- Building trust also requires transparency in company ownership to ensure subsidies are not being pocketed by the politically connected. For instance, the Panama Papers unmasked rampant stashing of stolen assets in anonymous companies; today 20 OGP countries, such as the UK and Slovakia, are opening up who really owns and controls companies – allowing journalists and citizen activists to follow the money and report illicit funds.

- Lobbying transparency will also enhance citizen trust by curbing influence peddling. In Ireland, where backroom deals contributed to their financial crisis, all meetings and gifts between lobbyists and public officials are now disclosed on a public register, which all lobbyists are required to join. More broadly, it is also vital to ensure that businesses and interest groups supported by stimulus packages – such as pharmaceutical companies, airlines, and the food industry – adopt these practices of lobbying transparency and beneficial ownershipDisclosing beneficial owners — those who ultimately control or profit from a business — is essential for combating corruption, stemming illicit financial flows, and fighting tax evasion. Technical... More transparency.

Beyond core open government practices, stakeholders can look specifically to past OGP commitments on how transparency, accountability and citizen engagement, including amplifying the voice of those traditionally excluded, have been integrated in post-disaster relief and stimulus packages. Notable examples of this work include:

- In the U.S. as an element of the $800 billion American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, the budget was made available in an open source format on recovery.gov, providing groundbreaking transparency on federal spending in one searchable location with interactive maps.

- In Fuerza Mexico, a digital platform was set up following the earthquakes in 2017 as a means to disclose data from agencies involved in emergency relief and reconstruction.

- In 2017, the Philippines committed to greater transparency and citizen oversight of disaster management, including a digital portal with comprehensive data on disaster response and a citizens’ complaints system on disaster management services.

- In Aceh, Indonesia after the 2004 Tsunami, community-led recovery through participatory mapping of risks and local planning enabled local communities to become safer and more resilient.

- In South Africa, the Budget Justice Coalition with civil society made recommendations on designing stimulus packages to focus on the needs of marginalized groups.

Health Systems Strengthening

The pandemic has exposed weak health systems in developing and developed countries alike. As countries move from emergency response to recovery, there will be a growing imperative to strengthen health systems. To that end, it will be vital to integrate transparency as well as citizen participation and oversight into these reforms so citizens receive the intended benefits, drawing on earlier OGP commitments such as:

- Facing shortages of safe drugs in government hospitals, Sri Lanka strengthened oversight by a multi-stakeholder advisory group; institutionalized a monitoring system on drug availability; and established a rating system for private pharmacies.

- North Macedonia committed in 2018 to improving its reporting standards for health programs, including user-centric impact assessments.

- In 2019, Mongolia disclosed data about health service contractors, empowered CSOs to oversee tender evaluations, and published healthcare information in a digital format.

Transparency and Accountability of Aid Flows

An integral part of recovery assistance in at least developing countries will come from enhanced aid flows. It becomes imperative for countries to put in place transparency and accountability measures to ensure that the aid truly reaches the intended beneficiaries. For developing countries, the aid may come in the form of budget support for which core open government practices referred above such as fiscal transparency, participatory budgeting, and open contracting become vital to build trust of donors and citizens alike.

Stakeholders can draw upon past OGP commitments to enhance transparency and civic oversight over aid or budgetary flows. For example:

- In Italy in 2014, when an investigative journalist revealed that only 9 percent of EU funds were being utilized, the government leveraged OGP to disclose, via an online Open Coesione platform, the details of 1 million projects, from large infrastructure to individual student grants, financed by 100 billion euros of EU funding. The transparency effort was complemented with a massive public awareness campaign to empower citizens, including high school students through school competitions to become on-the-ground citizen monitors of projects they cared about. For example, in Bovalino, a student-led initiative ensured funds were used to equip and reopen an abandoned community shelter to serve refugees and immigrants.

- In Kaduna, Nigeria, when an audit revealed that a health clinic existed only on paper, the State Budget Director partnered with citizens to become the eyes and ears of the government. Using a mobile app, people upload photos and provide feedback on projects like roads and health clinics. This feedback goes directly to the Governor’s Office and State Legislature for corrective action. In just two years, Kaduna reports record completionImplementers must follow through on their commitments for them to achieve impact. For each commitment, OGP’s Independent Reporting Mechanism (IRM) evaluates the degree to which the activities outlin... More of 450 schools and 250 health clinics, and a 20 percent reduction in maternal mortality.

OPEN REFORM

Restoring Civic Freedoms and Rolling Back State Surveillance

Even prior to COVID-19, we were witnessing an alarming rise in authoritarianism and attacks on basic civic freedoms in over 100 countries. The pandemic has further enabled a range of governments to rapidly centralize executive power, expand state surveillance, and restrict basic civic freedoms. A glaring example is Hungary, where Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has used COVID-19 to renew a state of emergency that prescribes five-year prison sentences for those purportedly disseminating false information or obstructing the state’s crisis response. The new law allows him to rule by decree indefinitely.

As countries move from response to recovery and beyond, attention will need to focus on deeper institutional reforms to re-empower the citizens, reversing restrictions on civic freedoms and new surveillance mechanisms that have been put in place to battle the pandemic, but risk staying ensconced over time.

Two key reforms have already emerged that must be advanced to re-empower citizens post COVID-19: restoring civic freedoms and independent oversight, and rolling back state surveillance.

Restoring Civic Freedoms and Independent Oversight: A clear trend in the COVID-19 response is heightened control over free expression and the media, under the guise of fighting “misinformation” about the virus. Another concerning risk is that governments may use the current need to restrict public gatherings as a pretext to crack down on anti-government protests.

Even as governments enact emergency powers, the enabling environment to hold elected officials accountable needs to be protected. If we are to create societies that can respond to the next disaster, we need to protect the truth-tellers, the whistleblowers, and oversight institutions. We need to ensure that scientists and experts have the ability to speak to oversight bodies and the public about their concerns. Independent media organizations play a critical role in holding governments accountable, but they too face cutbacks and shutterings during the pandemic. We need to protect citizens’ access to information to ensure oversight and accountability.

It is therefore critical that citizens and civil society continue to ask whether there is a specific time period after which restrictions on civic space will be reviewed and rolled back. Even prior to the pandemic, a priority in OGP was to push back against shrinking civic space – to protect and enhance citizens’ basic ability to freely speak, associate, and assemble, as well as journalists and activists’ ability to serve as vital intermediaries and watchdogs for citizens. Examples of OGP countries protecting or enhancing civic space:

- In South Korea, the government invited millions of citizens back to Gwanghwamun Square where candlelight protests had brought down the previous corrupt regime in 2017, asking citizens to propose policies that respond to their needs. The government continues to make concerted efforts to allow public spaces to be open to protestors.

- At a time when journalists have been harassed or killed in several parts of the world, Croatia has committed to strengthening protection mechanisms for journalists, and Mongolia committed to ensuring the independence of the media.

- Estonia has developed a national strategy for civic engagement and built the capacity of civil society to participate in policy making.

These examples are encouraging, but they are too few and far between. They need to be scaled up, particularly in the context of closing civic space in the response to COVID-19.

Rolling Back State Surveillance: Technology is playing a dominant role in the pandemic, most notably in its life-saving impact of allowing people to stay connected and work remotely to avoid getting infected or spreading infection. It has also allowed states to do contact tracing and curb the spread of the virus through state surveillance, which has saved lives. But given these enhanced state powers, how do we ensure responsible use of this state power? When will enhanced state surveillance be rescinded?

Three dimensions of risk to individual privacy and data protection that are important to mitigate include:

- Collection and Use of Health Data: Data collection, use, and sharing should be limited to what is strictly necessary for the fight against the virus.

- Tracking and Geo-Location: These can help track and curb contagion, but without proper safeguards, these tools can enable ubiquitous surveillance.

- Tech Platforms – Apps & Websites: While governments and tech companies work together on solutions during the pandemic (video-conferencing or disease-tracking apps), safeguards are needed to mitigate attendant risks to privacy and data protection.

These issues in the context of COVID-19 come on top of challenges that were already emerging in digital governanceAs evolving technologies present new opportunities for governments and citizens to advance openness and accountability, OGP participating governments are working to create policies that deal with the ... More such as external meddling in electionsImproving transparency in elections and maintaining the independence of electoral commissions is vital for promoting trust in the electoral system, preventing electoral fraud, and upholding the democr... More, the online spread of disinformation, and threats to individual privacy. We are already seeing nascent efforts in OGP countries to tackle these, such as: Canada committing to strengthen electoral laws to increase transparency around how voters are targeted by traditional and online advertising; Australia protecting citizen rights related to how data about them is collected and used; France, the Netherlands, and New Zealand improving government’s accountability to citizens with regard to using artificial intelligence and algorithms; and Mexico, following the earlier illegal surveillance of activists and journalists in 2017, committing to strengthen transparency of the surveillance systems. A group of OGP countries have joined forces to advance norms on digital governance. This could be leveraged to tackle new issues related to state surveillance, data protection, and privacy in relation to COVID-19.

Implications for OGP: Country, Thematic, and Global Levels

OGP provides a global platform that could be leveraged to advance open response, open recovery and open reform at the country, thematic, and global levels.

Country level: The pandemic has disrupted OGP co-creation processes. Fifty OGP countries were due to co-create new action plans in 2020, and that will likely be reduced to a handful at most. Even during this period, reformers involved in the OGP process, including OGP multi-stakeholder forums, can come together to work on concrete projects to make the response and recovery more open, including by adding reforms to current OGP action plans or preparing new plans. As countries resume economic activity, they can advance “open response, open recovery” by adding COVID-related commitments in action plans. This will require that civil society extend its base to broader groups of citizens impacted by COVID-19. On the side of governments, too, this will require broadening the base to ministries dealing with health, safety nets, and stimulus packages. Integrating COVID-19 related commitments in OGP action plans also holds the promise of enhancing learning and accountability through OGP’s Independent Reporting Mechanism which then assesses whether governments did what they said they would.

Thematic policy level: Prior to the pandemic, OGP was seeking to advance global norms of open government in key policy areas, such as open contracting, public service deliveryTo ensure that citizens of all groups are better supported by the government, OGP participating governments are working to improve the quality of and access to public services. Commitments in this are... More, access to justiceAccessible justice systems – both formal and informal – ensure that individuals and communities with legal needs know where to go for help, obtain the help they need, and move through a system tha... More, digital governance, gender, and civic space. Each of these thematic priorities remain relevant and important today. As they relate to COVID-19, they now take on additional dimension, for example:

- Ensuring open procurement of emergency medical supplies;

- Transparency and accountability in fiscal stimulus and health systems strengthening;

- Strengthening data and digital governance and tackling state surveillance;

- Tackling inequality in public services, fiscal measures and inclusionOGP participating governments are working to create governments that truly serve all people. Commitments in this area may address persons with disabilities, women and girls, lesbian, gay, bisexual, tr... More policies;

- Ensuring access to justice for the vulnerable adversely impacted by the pandemic; and

- Tackling the gender implications of the spike in domestic violence.

Global level: There will inevitably be debate about which type of political system – democracies or autocracies – would have been more effective at managing the crisis. While assessments will invariably be mixed and reliable data likely hard to come by, especially from authoritarian systems, we are already seeing the accelerating trend towards expanding executive powers and closing civic space during the pandemic. In this context, it will be vital for stakeholders committed to openness to join forces and advocate for open government practices in the recovery and reform efforts to follow. The pandemic underscores the importance of core values of transparency and citizen empowerment, collaboration across borders, and bringing in different perspectives including scientific expertise to solve collective challenges. It therefore becomes ever more pressing for stakeholders to forge a stronger global coalition for openness, pushing for and showcasing the value of open recovery and reform efforts to follow, to make open the way of the world post-COVID-19.

Call-to-Action: Building Trust – Through Openness – as the Antidote to COVID-19

Successful, and sustained, response and recovery to COVID-19 must include both efforts that leverage an engaged and empowered citizenry as well as those that build trust in government action. Trust in our public institutions has already suffered greatly in recent years. And a lack of trust during a crisis poses an existential risk. Indeed, building trust has never been more important – and, to that essential end, a new social compact, rooted in openness, can be the foundation for successful response and recovery.

Our review of early COVID-19 responses as well as lessons from past OGP commitments show concrete and practical ways in which openness – through transparency, citizen engagement and oversight – can build trust in response, recovery, and reform efforts. Building on these, we call on all stakeholders across government, civil society, parliamentarians, and the private sectorGovernments are working to open private sector practices as well — including through beneficial ownership transparency, open contracting, and regulating environmental standards. Technical specificat... More to join forces and implement concrete actions – including through OGP action plans – to advance open response, open recovery, and open reform over the long-term. Specifically:

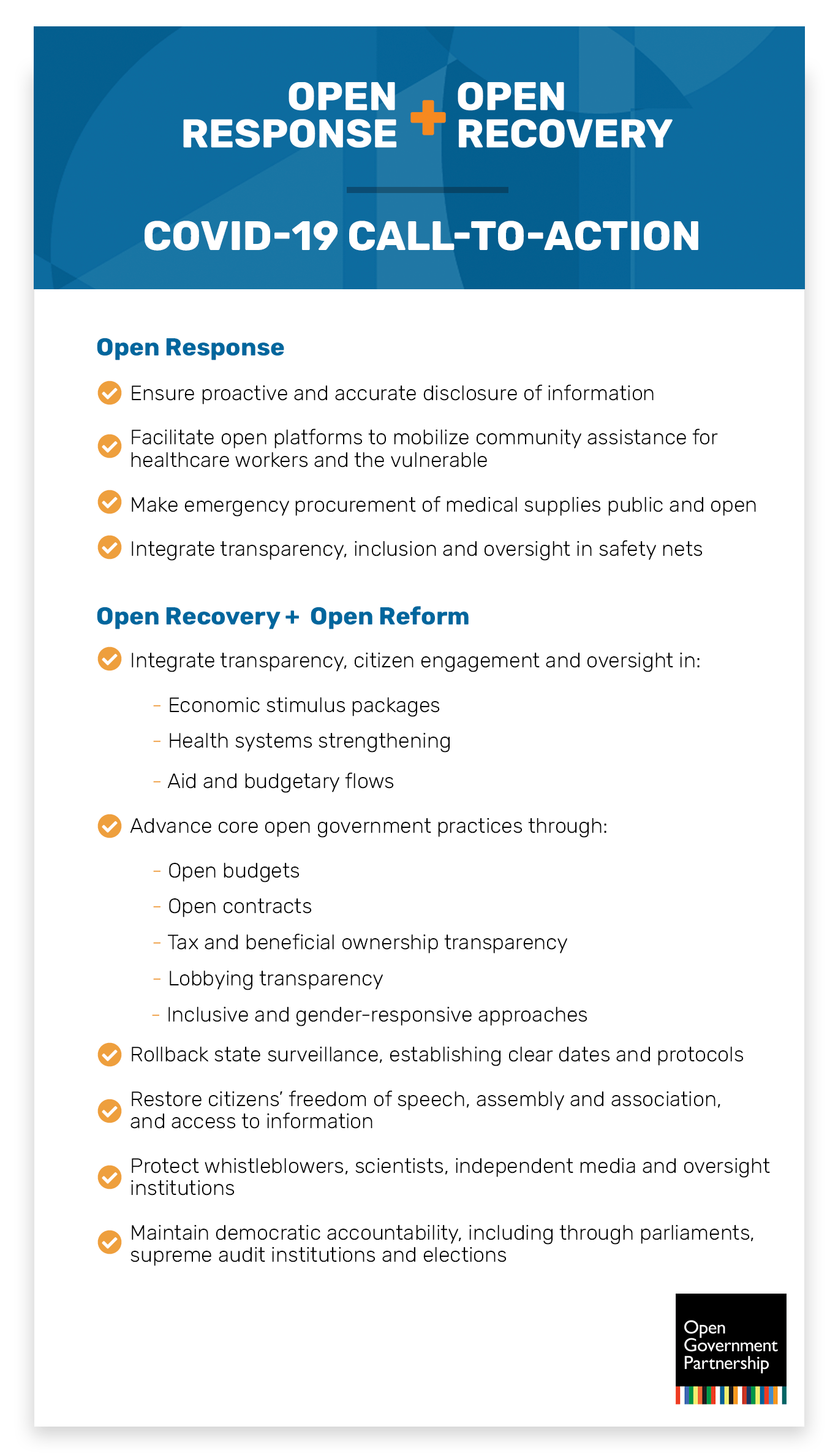

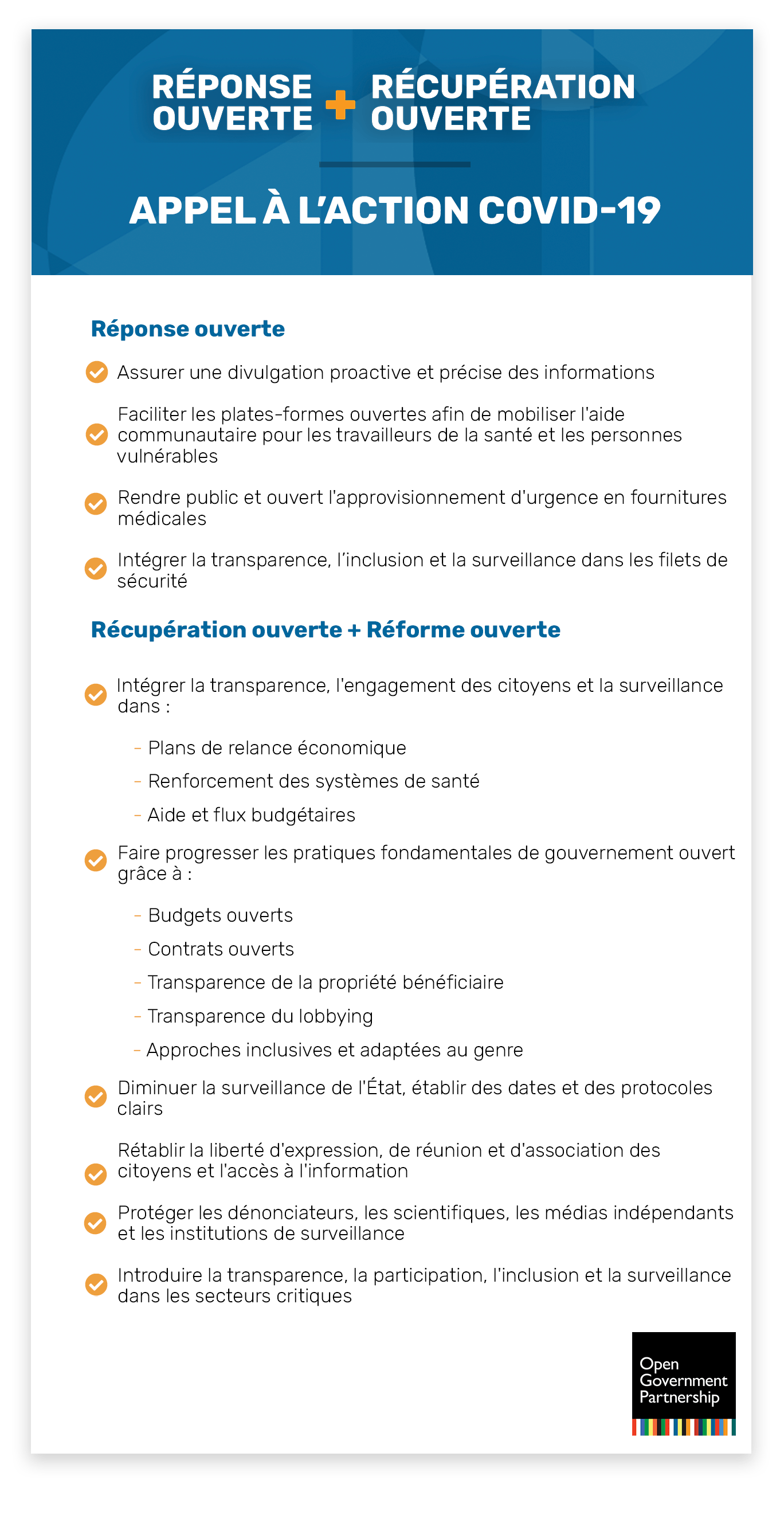

- For Open Response:

- Ensure proactive and accurate disclosure of information

- Facilitate open platforms to mobilize community assistance for healthcare workers and the vulnerable

- Make emergency procurement of medical supplies public and open

- Integrate transparency, inclusion, and oversight in safety nets

- For Open Recovery:

- Integrate transparency, citizen engagement and oversight in:

- Economic stimulus packages

- Health systems strengthening

- Aid and budgetary flows

- Advance core open government practices through the recovery program

- Open budgets

- Open contracts

- Beneficial ownership transparency

- Lobbying transparency

- Inclusive and gender-responsive approaches

- Integrate transparency, citizen engagement and oversight in:

- For Open Reform over the long-term:

- Roll back state surveillance, establishing clear dates and protocols

- Restore citizens’ freedom of speech, assembly and association, and access to information

- Protect whistleblowers, scientists, independent media and oversight institutions

- Introduce transparency, participation, inclusion and oversight in critical sectors

Not only will this approach be more effective in the near term in curbing contagion, mobilizing care, and ensuring that the massive stimulus packages and safety nets reach the vulnerable, this lays the groundwork for stronger, more resilient systems over time. Decades of research have shown that more open, inclusive, and accountable societies are more resilient societies – better able to adapt to shocks, to build consensus among sectors of society, and to address the inequality at the root of so many of the disparate effects of disasters.

At its core, all of this calls for a longer-term shift to a governance model which puts citizens at the heart of government. Citizens have a vital role to play in this emergency, as they do in everyday life. And this belief is also at the heart of open government: bringing together government leaders with citizen groups from all walks of life to co-create plans and solutions so citizens are empowered to shape and oversee decisions that impact their lives. Citizens are bearing the brunt of the pandemic. Let us empower them to respond and recover. Joining forces to build trust – underpinned by openness – will prove to be the most powerful antidote to COVID-19.

Download the PDF version of the report here.

Bibliography

Access Now. “Recommendations on Privacy and Data Protection in the Fight Against COVID-19.” March 2020.

Brown, Frances Z, Saskia Brechenmacher, and Thomas Carothers. “How Will the Coronavirus Reshape Democracy and Governance Globally?” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, April 6, 2020.

The Economist. “Let Taiwan Into the World Health Organization.” March 26, 2020.

The Editorial Board. “The America We Need.” The New York Times, April 9, 2020.

Francis Fukuyama. “The Thing that Determines a Country’s Resistance to the Coronavirus: The Major Dividing Line in Effective Crisis Response Will Not Place Autocracies on One Side and Democracies on the Other.” The Atlantic, March 30, 2020.

Gebrekidan, Selam. “For Autocrats, and Others, Coronavirus Is a Chance to Grab Even More Power.” The New York Times, March 30, 2020.

Harari, Yuval Noah. “Yuval Noah Harari: The World After Coronavirus.” Financial Times, March 20, 2020.

Harding, Andrew. “South Africa’s Ruthlessly Efficient Fight Against Coronavirus.” BBC News, April 3, 2020.

Hayman, Gavin. “Emergency Procurement for COVID-19: Buying Fast, Open and Smart.” Open Contracting Partnership, March 25, 2020.

Kavanagh, Matthew. “Transparency and Testing Work Better Than Coercion in Coronavirus Battle.” Forign Policy. March 16, 2020.

Kirk, Donald. “South Korea is Beating the Coronavirus. Mass Testing is Key. But There’s More.” The Daily Beast, March 13, 2020.

Kleinfeld, Rachel. “Do Authoritarian or Democratic Countries Handle Pandemics Better?” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, March 31, 2020.

Kupperman Thorp, Tammy. “To Defeat the Coronavirus, Stop Corruption.” Foreign Policy, April 6, 2020.

Lanier, Jaron and E. Glen Weyl. “How Civic Technology Can Help Stop a Pandemic – Taiwan’s Initial Success Is a Model for the Rest of the World.” Foreign Affairs, March 20, 2020.

Rivero Del Paso, Lorena. “Fiscal Transparency in Times of Emergency Response: Reflections for Times of COVID-19.” Global Initiative for Fiscal Transparency, March 19, 2020.

Sen, Amartya. “Overcoming a Pandemic May Look Like Fighting a War, But the Real Need is Far from That.” The Indian Express, April 13, 2020.

Tharoor, Ishaan. “Coronavirus Kills Its First Democracy.” The Washington Post, March 31, 2020.

Tennison, Jeni. “Why Isn’t the Government Publishing More Data About Coronavirus Deaths?” The Guardian, April 2, 2020.

Tisdall, Simon. “Power, Equality, Nationalism: How The Pandemic Will Reshape the World.” The Guardian, March 28, 2020.

Torres, Liv. “SDG16+ – The Key to Managing the COVID-19 Crisis.” Pathfinders for Peaceful, Just and Inclusive Societies, March 18, 2020.

Transparency International. “In Times Like These, Transparency Matters More Than Ever.” March 19, 2020.

Wright, Nicolas. “Coronavirus and the Future of Surveillance: Democracies Must Offer an Alternative to Authoritarian Solutions.” Foreign Affairs, April 6, 2020.

Respuesta abierta, recuperación abierta

La confianza como el antídoto a COVID-19

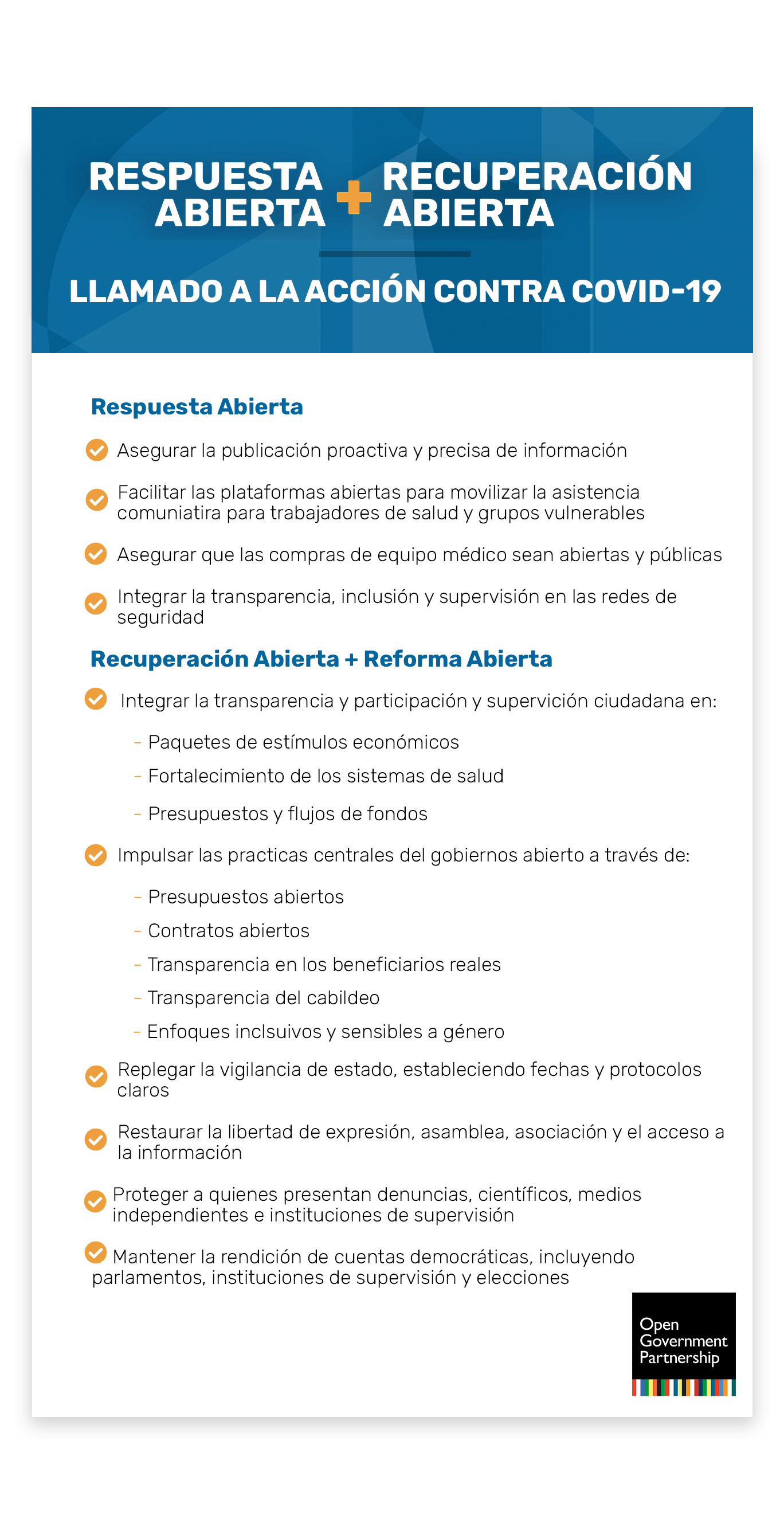

Resumen Ejecutivo La pandemia de COVID-19 ha orillado a los gobiernos y ciudadanos a tomar medidas de mitigación sin precedentes. En esta lucha común, la confianza mutua entre el gobierno y la ciudadanía puede ser la clave del éxito para la respuesta y la recuperación. “Respuesta abierta, recuperación abierta” puede llevar a la confianza mutua: cuando los gobiernos publican sus disposiciones para frenar el contagio de forma transparente, empoderan a los ciudadanos a tomar medidas responsables de mitigación; los ciudadanos empoderan a los gobiernos para desplegar sus acciones de emergencia, movilizar tratamiento médico en masa y presentar paquetes de estímulos, siempre que los gobiernos actúan con integridad, tienen apertura al escrutinio público y repliegan las acciones de emergencia tras la pandemia. En esta publicación, presentamos algunas formas concretas y prácticas en que la apertura – a través de la transparencia y la participación y supervisión ciudadanas – puede ayudar a resolver las tres fases de la pandemia: respuesta, recuperación y reformas de largo plazo. Este análisis se fundamenta en cerca de una década de experiencia con Open Government Partnership, incluyendo más de 4 000 reformas de gobierno abierto cocreados con la participación de reformadores de gobierno y la sociedad civil en más de 78 países, así como más de 200 intervenciones contra COVID-19 que identificamos con la colaboración de la comunidad. Respuesta abierta:

Recuperación abierta:

Reformas para el largo plazo: En el proceso de recuperación de las sociedades, será necesario empoderar a los ciudadanos, replegando las restricciones a las libertades cívicas y los mecanismos de supervisión implementados para frenar el contagio. Además, para fortalecer su resiliencia frente al próximo desastre, es necesario proteger a quienes presentan denuncias, a los científicos y a los medios independientes. Durante las diferentes fases de la pandemia, estaremos publicando, en tiempo real, lecciones aprendidas sobre las respuestas implementadas. Este llamado a la acción resume algunos puntos de partida de inspiración para los interesados. Esperamos que nos ayudes a definir un nuevo modelo de gobernanza en el que los ciudadanos son el centro del gobierno, desarrollando la confianza – fundamentada en la apertura – como el antídoto más potente contra COVID-19.

|

Introducción

Enfrentar una calamidad social no es como pelear una guerra que funciona mejor cuando un líder utiliza el poder vertical para ordenar a los demás lo que el líder quiere, sin necesidad de consultar. Por el contrario, para atender una calamidad social es necesaria la gobernanza participativa y alertar una discusión pública.

La pandemia del coronavirus ha ocasionado un sufrimiento extraordinario a los ciudadanos de todo el mundo, ocasionando la pérdida de seres queridos, de empleo y de paz mental. Los trabajadores esenciales con gran valentía están prestando servicios fundamentales – como la atención médica y la provisión de alimentos. Por su parte, la ciudadanía se está enfrentando a la gran responsabilidad de tomar acciones de mitigación y supervivencia: cumplir cuarentenas en sus casas, cuidar de sus familiares enfermos y sobrevivir a pesar del desempleo. Al mismo tiempo, el papel que los gobiernos deben cumplir para la protección y el apoyo a sus ciudadanos hoy es más apremiante que nunca. En el norte y en el sur, en países desarrollados y en vías de desarrollo, en la derecha y la izquierda, el consenso es que es necesario contar con medidas fuertes y contundentes por parte de los gobiernos para contener los contagios, ofrecer tratamiento médico en masa a los pacientes infectados, proteger a las poblaciones más vulnerables y promover la recuperación económica y reactivar el empleo.

Pero, ¿Cómo están colaborando los gobiernos con la ciudadanía a la que deben proteger y ayudar? ¿Cómo la están empoderando? ¿Cómo se están relacionando los ciudadanos con sus gobiernos, en un espíritu de confianza mutua? ¿Cómo pueden trabajar los gobiernos y los ciudadanos conjuntamente para luchar contra un enemigo común?

En el contexto de la pandemia, los gobiernos de todo el mundo están adoptando una gran variedad de estrategias para controlar o empoderar a sus ciudadanos, desde un enfoque totalitario de vigilancia y control en China hasta una política de libertad en Suecia que confía en que la ciudadanía informada tomará decisiones responsables. Estas medidas reflejan la diversidad de regímenes políticos y los diferentes niveles de participación cívica, cohesión social y penetración tecnológica que existen en el mundo. La efectividad de estas medidas no dependerá únicamente del tipo de régimen, pues ni las autocracias ni las democracias han sido completamente exitosas, incluso en las fases tempranas de la pandemia. La efectividad, en última instancia, dependerá de una serie de factores subyacentes como la capacidad del estado – incluyendo la solidez de los sistemas de salud – y la medida en la que los ciudadanos confían en sus estados y líderes.

En todas las medidas contra la pandemia, los ciudadanos no son únicamente sujetos pasivos o beneficiarios de las acciones y el control de los gobiernos, sino agentes activos y fundamentales, socios y aliados en esta lucha común – tomando decisiones responsables para protegerse a sí mismos y al resto de la población frenando los contagios, así como definiendo y supervisando los esfuerzos de recuperación de los gobiernos. La clave de la respuesta efectiva y la recuperación es el interés generalizado de la población de ser contribuyentes en estos esfuerzos y la confianza en las acciones de sus gobiernos. Antes de la pandemia, la confianza de los ciudadanos en las instituciones se había desplomado a niveles históricamente bajos en muchos países, amenazando la participación ciudadana en las acciones de respuesta y recuperación. Las intervenciones de gobierno abierto: “Respuesta abierta, recuperación abierta” pueden ayudar a reconstruir la confianza y empoderar a los ciudadanos. Éstas pueden crear un ambiente en el que los ciudadanos responden a las disposiciones de sus gobiernos para frenar los contagios cuando éstas son transparentes, confiables y proactivas y los gobiernos confían en que sus ciudadanos tomarán decisiones responsables y los ciudadanos empoderan a sus gobiernos de manera que desplieguen acciones de emergencia, paquetes de estímulos económicos y redes de seguridad, mientras que los gobiernos actúan responsablemente, muestran apertura al escrutinio público y hacen retroceder sus acciones de emergencia una vez que la pandemia haya cedido.

La confianza – fundamentada en la apertura – debe ser la base del nuevo acuerdo social que es necesario para impulsar una respuesta efectiva y duradera a COVID-19. Ésta puede ayudar a cultivar un cambio duradero a un modelo de gobernanza, con los ciudadanos en el centro.

En este contexto, revisaremos algunas respuestas tempranas a COVID-19, así como algunas lecciones aprendidas de intervenciones pasadas para estudiar de qué forma el gobierno abierto puede fortalecer la confianza e incrementar la efectividad de las medidas de respuesta a la pandemia y recuperación posterior. Open Government Partnership (OGP), a través de un esfuerzo de colaboración masiva (crowdsourcing), identificó 200 estrategias de gobierno abierto entre las respuestas al COVID-19 que ha desplegado nuestra comunidad de 78 países, gobiernos locales y miles de organizaciones de la sociedad civil. Además, incluimos algunas lecciones aprendidas relevantes de los más de 4 000 compromisos que hemos implementado en los últimos 9 años y que han quedado reflejados en más de 250 planes de acción de OGP cocreados por reformadores de gobierno y de la sociedad civil con el fin de lograr que los gobiernos sean más abiertos participativos y responsables con sus ciudadanos.

A continuación, analizamos cómo las intervenciones de gobierno abierto – transparencia por parte de los gobiernos y participación y supervisión por parte de los ciudadanos – pueden ayudar a abordar las tres fases o componentes de la respuesta y recuperación de la pandemia.

- Open Response: frenar los contagios, escalar el tratamiento médico y ofrecer redes de seguridad a los grupos más vulnerables.

- Open Recovery: fomentar paquetes de estímulos y recuperación, fortalecer los sistemas de salud y asegurar la transparencia y rendición de cuentas de los fondos de asistencia

- Reforma abierta: reformar a las instituciones y reempoderar a los ciudadanos, replegando las acciones de vigilancia y restaurando las libertades cívicas y la supervisión independiente

RESPUESTA ABIERTA

Frenar el contagio: Empoderar a los ciudadanos con información proactiva y correcta

Incluso durante las fases iniciales de la propagación del virus, se han registrado costos devastadores como resultado de la falta de transparencia de algunos gobiernos, así como de sus acciones tempranas. Algunos gobiernos han minimizado u ocultado la gravedad de la pandemia, retrasando la publicación de los riesgos y amenazas que ésta representa para los ciudadanos. Lo anterior comprometió vidas de personas que podrían salvarse con la publicación proactiva de información y con la implementación de medidas tempranas.

En China, Irán y Estados Unidos, la negación que se dio al inicio permitió que el virus se propagara de forma descontrolada. En China, las primeras personas que dieron señales de alerta fueron amenazadas y se bloqueó información que debió ser de acceso público. En contraste, gobiernos como Corea del Sur y Taiwán ocurrió lo contrario: se publicó información proactiva, clara, transparente y confiable para empoderar a los ciudadanos a tomar acciones de mitigación.

La diversidad de enfoques y resultados reflejan diferentes composiciones de confianza mutua entre el estado y la sociedad, así como diferentes niveles de empoderamiento de los ciudadanos.

Por ejemplo, a finales de enero, después de que no informaron al público de la situación y de la multiplicación de los contagios, China desplegó la autoridad del estado para imponer cuarentenas y herramientas de supervisión a sus ciudadanos, monitoreando los teléfonos de las personas, utilizando cientos de millones de cámaras con reconocimiento facial y obligando a las personas a enviar informes con su temperatura corporal. Al mismo tiempo, el estado reclutó a una enorme cantidad de ciudadanos voluntarios y personal de atención médica

En Corea del Sur, los éxitos del gobierno se lograron en gran medida gracias a la aplicación masiva de pruebas, con lo que se generaron datos para aislar a las personas infectadas y romper la cadena de transmisión. Además, Corea del Sur confió en la transparencia, participación ciudadana, reportes honestos y la disponibilidad a cooperar por parte de sus ciudadanos, quienes confiaban en el gobierno. La participación se logró a través de una política de apertura y transparencia, incluyendo sesiones informativas diarias y una campaña de sensibilización diseñada para promover el distanciamiento social.

Taiwán logró mantener un nivel notablemente bajo de infecciones y muertes, no a través de un control vertical, sino a través de la transparencia gubernamental, la cual construyó la transparencia del público y promovió la coordinación social. Por ejemplo, a través de la aplicación “cubre bocas”, el gobierno publicó datos en tiempo real y con precisión geográfica sobre la disponibilidad de cubre bocas, empoderando a los ciudadanos para colaborar y redistribuir raciones y donaciones a quienes más lo necesitaban.

Estas medidas se están implementando en tiempo real como respuesta a la pandemia. Sin embargo, existen ejemplos previos que podemos retomar para demostrar que la apertura y la transparencia pueden salvar vidas. Por ejemplo, en 2011 en el Reino Unido, una consulta pública encontró que las tasas de mortalidad de los bebés que se sometieron a cirugías de corazón en el hospital Bristol Royal eran dos veces más altas que las tasas de otros hospitales. Tras la consulta, los cirujanos cardiovasculares de todo el Servicio Nacional de Salud empezaron a publicar datos sobre la tasa de mortalidad de las cirugías de corazón para ayudar a las personas a tomar mejores decisiones. Como resultado, la tasa de mortalidad de los bebés sometidos a cirugías del corazón se redujo en un 33%. Empoderar a los ciudadanos con información proactiva y precisa tiene el poder de salvar vidas.

En nuestro esfuerzo de identificación de respuestas al COVID-19 registradas en los países de OGP, notamos que algunos gobiernos están estableciendo una comunicación clara, precisa y transparente con el público para informarlos, educarlos y trabajar con ellos, lo anterior con base en evidencia y experiencia científica sólidas. A continuación presentamos algunos ejemplos que reportan los miembros de la comunidad de OGP:

- Portales con datos en tiempo real sobre infecciones, muertes y la localización de casos de COVID-19 (Argentina, Canadá, Costa de Marfil, Italia, Jordania, Perú, Sudáfrica y Túnez)

- Conferencias de prensa diarias con datos precisos para informar al público y detener la propagación de información falsa (Corea del Sur, Singapur)

- Servicios de mensajería automáticos a través de WhatsApp o Facebook que responden a preguntas frecuentes sobre la pandemia (Buenos Aires- Argentina, Marruecos y Ucrania)

- Mapas virtuales que permiten el análisis de datos de COVID-19, incluyendo sitios en cuarentena, la cantidad de personas infectadas y recuperadas y el personal médico disponible por municipio (Lituania)

Escalamiento de tratamiento y atención médica: Promoción de la participación y supervisión ciudadana

Escalar el tratamiento y atención médica para para un número de pacientes que crece de forma exponencial es el reto más significativo. La pandemia está implicando la saturación de los sistemas de salud de todo el mundo. En ese sentido, identificamos dos áreas en las que las intervenciones de gobierno abierto pueden ser de utilidad: (i) la movilización de la asistencia comunitaria para la atención médica y (ii) la apertura de las compras de equipo médico.

Movilizar la asistencia comunitaria para la atención médica: En todos los países, los médicos, enfermeras, terapeutas y otros profesionales de la salud están luchando de forma desinteresada para salvar a sus pacientes. La pandemia ha desencadenado un sentido de comunidad, en muchos casos con el apoyo de la tecnología y las aplicaciones informáticas. En las primeras fases, las respuestas a COVID-19 que identificamos gracias a la comunidad de OGP, registramos diversas plataformas abiertas diseñadas para movilizar ayuda comunitaria a los trabajadores de la salud y a los grupos más vulnerables. A continuación incluimos algunos ejemplos:

- Plataformas abiertas y aplicaciones que permiten a los médicos y a los hospitales monitorear a pacientes infectados o con sospecha de infección manteniendo a los pacientes en sus hogares (Francia, Italia)

- Una plataforma de apoyo a los trabajadores de la salud para cuidar a sus hijos (Francia)

- Plataformas voluntarias para atender a los adultos mayores que han enfermado (Bulgaria, Georgia)

- Hackatones para movilizar trabajadores esenciales, asistencia comunitaria e iniciativas innovadoras (Alemania, Colombia, Estonia y Letonia)

- Colaboración masiva para identificar soluciones a la escasez de equipo médico a través del grupo de Facebook Open Source COVID-19 Medical Supplies

Apertura de las compras de equipo médico:

En muchos países, las compras públicas asociadas a la respuesta a la pandemia de coronavirus son un asunto de vida o muerte. La escasez de equipo de protección personal para los trabajadores de primera línea, de ventiladores y de pruebas ha dificultado la respuesta efectiva. Cuando los gobiernos se apresuran a comprar estos recursos vitales y omiten las salvaguardas que normalmente se aplican en los contratos de compras públicas, se pueden registrar fraudes, sobornos y artículos falsos. Por ejemplo, en 2010, el Global Fund hizo pagos de millones de dólares para comprar 6 millones de redes con insecticida para evitar la malaria en Burkina Faso, pero cerca de 2 millones de esas redes resultaron ser falsas.

Para abordar los retos que implica la necesidad de los gobiernos de realizar compras de emergencia con rapidez, es necesario que los procesos sean públicos y abiertos para mantener la confianza del público. Por ejemplo, las reformas anticorrupción de Ucrania exigen la publicación de todos los contratos en su totalidad y en formato de datos abiertos. La sociedad civil desarrolló una herramienta de inteligencia de negocios para monitorear los procesos de compras públicas y los gastos de emergencia. Con ella, pueden dar seguimiento a los diferentes precios de las pruebas de COVID-19 y demás equipo médico para asegurar que las autoridades están comprometidas con los centros médicos y no con intereses privados. La sociedad civil está actuando como un aliado clave para asegurar que los recursos se utilicen para los fines establecidos, aunque algunos elementos del gobierno han sido acusados de fraudes.

En Latinoamérica, Transparencia Internacional conformó un grupo de trabajo de 13 países para identificar riesgos en las compras públicas como respuesta a COVID-19 – opacidad, contratos ocultos, costos excesivos, colusiones y falta de competencia – así como medidas para mitigarlos.

Redes de seguridad para los grupos más vulnerables: Inclusión y empoderamiento de los excluidos

El paro económico asociado a COVID-19 ha devastado a los grupos más pobres y vulnerables, pues son ellos quienes tienen menor capacidad de resistir el impacto. Los grupos que ya eran vulnerables están perdiendo su empleo y muchos de ellos carecen de los recursos para sobrevivir más allá de unos días. En la India, la cuarentena más importante de la historia (mil trescientos millones de personas) resultó en la pérdida de empleo para millones de migrantes trabajadores, quienes se han quedado varados en ciudades o se han visto obligados a viajar a sus localidades remotas, con los riesgos que ello conlleva. Estos grupos tan vulnerables están en riesgo de morir de pobreza o hambre antes que de COVID-19.

En respuesta, los gobiernos ya están implementando medidas de emergencia para ofrecer redes de seguridad, por ejemplo: programas alimentarios, subsidios a la nómina y seguros de empleo. Algunos ejemplos reportados por la comunidad de OGP son:

- Transformación de identificaciones oficiales en tarjetas de débito para ofrecer apoyo para medicamentos y alimentos a los más vulnerables (Panamá)

- Simplificación de solicitudes de desempleo para aquellos que perdieron su empleo por el paro (Irlanda)

- Creación de un fondo especial para ayudar a las familias que lo necesitan (Lituania)

- Comités ciudadanos creados para llevar alimento a los grupos vulnerables (Jordania)

Una prioridad fundamental debe ser asegurar la transparencia y la supervisión ciudadana de los programas para asegurar que en efecto lleguen a las personas que lo necesitan. Algunos ejemplos que tomamos de compromisos previos de OGP:

- Publicación de presupuestos y resultados de los programas de atención a la pobreza, incluyendo disposiciones que permiten a los ciudadanos monitorear y solicitar información (Indonesia)

- Participación y monitoreo ciudadano de Programa Nacional de Reducción de la Pobreza, entre otros medios a través de auditorías sociales y mecanismos de retroalimentación ciudadana (Paraguay)

- Presupuestos participativos para planes locales contra a pobreza en 595 municipios (Filipinas)

- Publicación de más de 1 600 indicadores asociados a los programas sociales, permitiendo a los periodistas y ciudadanos monitorear los avances (Uruguay)

- Sistemas de mapeo de personas en situación de calle con insumos de las personas y comunidades afectadas sobre la calidad de los servicios (Austin, Estados Unidos)

Los esfuerzos para proteger a los grupos vulnerables durante la pandemia deben conservar las discusiones públicas y los medios independientes como mecanismos de supervisión para evitar agravar la situación de los grupos en riesgo. Como menciona Amartya Sen en su trabajo sobre cómo se evitaron hambrunas en la India tras su Independencia, “aunque solamente la minoría se enfrente a la hambruna, una mayoría que escucha, informada gracias a las discusiones públicas y a la prensa, puede lograr que los gobiernos respondan.”

Las agendas enfocadas en apoyar a quienes fueron afectados por COVID-19 no deberán enfocarse únicamente en los desfavorecidos económicamente, sino también a los impactados socialmente. Por ejemplo, un impacto devastador de las cuarentenas por COVID-19 es el alza en la violencia doméstica en todo el mundo, la cual afecta principalmente a las mujeres. Los interesados pueden aprender de los compromisos pasados de OGP para fortalecer los servicios a los supervivientes de violencia doméstica, como el caso de Ecuador que reunió datos para la prevención y erradicación de la violencia de género.

RECUPERACIÓN ABIERTA

Transparencia y rendición de cuentas de los paquetes de estímulos

La pandemia probablemente ocasionará una recesión muy importante a nivel global, por lo que será necesario desplegar enormes paquetes para reavivar la economía. La rapidez y capacidad de respuesta son fundamentales para la recuperación. Sin embargo, la transparencia y la supervisión de los paquetes de estímulos son clave para asegurar que los recursos se apliquen adecuadamente y que se mantenga la confianza de la ciudadanía en sus gobiernos. En la práctica, esto implica que los mecanismos de control interno de los gastos públicos sean más flexibles, asegurando que se mantengan los registros de las auditorías y que se auditen los fondos públicos. Además, es necesaria la transparencia en cuanto a la asignación de rescates y subsidios, en la toma de decisiones y en asegurar que los fondos no se capturen por las élites o campañas políticas. Los estímulos y programas de recuperación, además, deberá abordar los retos de desigualdad que han sido exacerbados por COVID-19 como la selección de las personas a quienes se ha aplicado pruebas y a quienes no, los privilegiados que se recluyen en sus hogares mientras que trabajadores que no tienen prestaciones les entregan comida a domicilio o niños de familias de bajos recursos que no tienen acceso a clases virtuales para continuar sus estudios entre muchas otras.

Para diseñar paquetes de estímulos para responder a estos retos, los interesados pueden tomar lecciones aprendidas de dos grupos de experiencias de OGP: un conjunto de reformas centrales de gobierno abierto y, de forma particular, la experiencia de compromisos pasados sobre paquetes de estímulos y programas de atención a desastres.

Algunas prácticas centrales de gobierno abierto de compromisos pasados en los programas fiscales y la asignación de subsidios y rescates:

- Para mantener la confianza ciudadana, es fundamental que a la asignación de contratos públicos financiados por los grandes paquetes económicos se apliquen los principios de la contratación abierta. Por ejemplo, para detener la captura de las compras públicas por la oligarquía, reformadores de Ucrania crearon dos plataformas digitales (ProZorro y DoZorro) que contienen todos los contratos en formato de datos abiertos, de manera que los ciudadanos puedan consultarlos y reportar irregularidades. En solo dos años, los ciudadanos identificaron más de 14 000 violaciones, llevando a mil millones de dólares en ahorros, a una menor corrupción reportada por el 82% de los empresarios y a un aumento del 50% de las licitaciones. Hasta el momento, 70 gobiernos de OGP se han comprometido a implementar contratos abiertos.

- La construcción de la confianza requiere de transparencia en los beneficiarios de las empresas para asegurar que los subsidios no sean capturados por actores con vínculos políticos. Por ejemplo, los Panama Papers descubrieron enormes cantidades de bienes robados a través de empresas anónimas. Hoy 20 países de OGP, incluyendo al Reino Unido y a Eslovaquia, se está abriendo la información sobre quienes controlan las empresas, lo que ha permitido a los periodistas y activistas dar seguimiento al dinero y reportar fondos ilícitos.

- La transparencia en los procesos de cabildeo también contribuyen a fortalecer la confianza ciudadana al reducir el tráfico de influencias. En Irlanda, en donde la crisis financiera fue en parte resultado de acuerdos ilícitos, hoy todas las reuniones y obsequios entre cabilderos y funcionarios se publican en un registro público al que todos los cabilderos tienen la obligación de incorporarse. Además, también es fundamental que las empresas y grupos de interés que reciben apoyos asociados a los paquetes de estímulos, por ejemplo las empresas farmacéuticas, aerolíneas y la industria alimenticia, adopten prácticas de transparencia en sus procesos de cabildeo y en los beneficiarios reales

Además de las prácticas centrales de gobierno abierto, los interesados pueden estudiar algunos compromisos anteriores sobre cómo la transparencia, rendición de cuentas y participación ciudadana – incluyendo la inclusión de las voces tradicionalmente excluidas – han sido integradas en programas de atención a desastres y paquetes de estímulos. Algunos ejemplos destacados de ello son:

- En Estados Unidos, como elemento de la Ley de Recuperación y Reinversión que consistió en $800 mil millones, se publicó el presupuesto en formato de datos abiertos en el portal recovery.gov en un acto revolucionario de transparencia de los gatos federales, unificado en un solo sitio con mapas interactivos.

- La plataforma digital Fuerza México se estableció tras el sismo de 2017 como herramienta para la publicación de datos de las instituciones involucradas en la atención a la emergencia y la recuperación.

- En 2017, Filipinas se comprometió a dar mayor transparencia y a promover la supervisión ciudadana del manejo de desastres, incluyendo una plataforma digital que incluye datos de atención a respuesta y un sistema de quejas sobre los servicios de atención a desastres.

- En Aceh, Indonesia, tras el Tsunami de 2004 los procesos comunitarios de recuperación a través de un mapeo participativo de los riesgos y procesos de planeación local ayudaron a las comunidades a ser más seguras y resilientes.

- En Sudáfrica, la Coalición de Justicia Presupuestaria, en coordinación con la sociedad civil, presentaron recomendaciones para asegurar que el diseño de paquetes de estímulos se enfocara en las necesidades de los grupos marginados.

Fortalecimiento de los sistemas de salud

La pandemia ha demostrado las debilidades de los sistemas de salud, tanto en los países en vías de desarrollo como en los desarrollados. En el proceso de transición de emergencia hacia la recuperación, será fundamental fortalecer los sistemas de salud. Para ello, deberemos integrar la transparencia y la participación y supervisión ciudadanas en estas reformas de manera que los ciudadanos reciban los beneficios esperados. En ese sentido, los siguientes compromisos de OGP pueden servir como referencia:

- En un contexto de escasez de medicamentos en los hospitales públicos, Sri Lanka incrementó la supervisión a través de un grupo asesor multisectorial, institucionalizó un sistema de monitoreo de la disponibilidad de medicamentos y estableció un sistema de evaluación de las farmacias privadas.

- Macedonia del Norte se comprometió en 2018 a mejorar sus estándares de reporte de los sistemas de salud, incluyendo evaluaciones de impacto enfocadas en los usuarios.

- En 2019, Mongolia publicó datos sobre los proveedores de servicios de salud, empoderó a las OSC para supervisar las evaluaciones y publicó información sobre los servicios de salud en formato digital.

Transparencia y rendición de cuentas de los fondos de asistencia

Una gran parte de la asistencia para la recuperación, al menos en los países en vías de desarrollo, procederá de fondos de asistencia. En ese sentido, los países deberán implementar medidas de transparencia y rendición de cuentas para asegurar que la asistencia efectivamente llegue a los beneficiarios esperados. En el caso de los países en desarrollo, la asistencia podrá reflejarse en forma de presupuesto, por lo que las prácticas centrales del gobierno abierto como la transparencia, presupuestos participativos y contratación abierta serán clave para fortalecer la confianza de los donantes y los ciudadanos.

Los interesados pueden inspirarse en compromisos de OGP pasados para fortalecer la transparencia y la supervisión ciudadana de los fondos. Por ejemplo:

- En Italia en 2014 un periodista reveló que solamente el 9% de los fondos de la Unión Europea estaban siendo utilizados. En ese contexto, el gobierno aprovechó el proceso de OGP para publicar en una plataforma información relacionada con 1 millón de proyectos (100 mil millones de euros), desde grandes proyectos de infraestructura hasta becas a estudiantes. Estos esfuerzos de transparencia se complementaron con una campaña de sensibilización diseñada para empoderar a los ciudadanos, incluyendo un programa dirigido a estudiantes de secundaria en el que participan como monitores ciudadanos en proyectos de su interés. Por ejemplo, en Bovalino, una iniciativa liderada por estudiantes aseguró que los fondos se aplicaran para equipar y reabrir un refugio comunitario para atender a refugiados y migrantes.

- En Kaduna, Nigeria, una auditoría reveló que una clínica de salud solamente existía en el papel, por lo que el director de presupuestos se asoció con los ciudadanos y les pidió ser los ojos y oídos del gobierno. Utilizando una aplicación móvil, la gente puede publicar fotografías y retroalimentación sobre proyectos públicos como caminos o clínicas de salud. La retroalimentación se dirige directamente a la oficina del gobernador y a la legislatura del estado de manera que puedan aplicar acciones correctivas. En solo dos años, Kaduna reportó la construcción de 450 escuelas y 250 clínicas de salud, así como una reducción de la mortalidad materna en un 20%.

REFORMAS ABIERTAS

Restauración de las libertades cívicas y repliegue de la vigilancia estatal

Incluso antes de la pandemia de COVID-19, en el mundo se registraba un alza alarmante en el autoritarismo y los ataques a las libertades cívicas en más de 100 países. La pandemia ha permitido que una serie de países centralicen aún más el poder ejecutivo, incrementen la vigilancia y restrinjan las libertades básicas. Un ejemplo claro de ello es Hungría, en donde el primer ministro Viktor Orbán está utilizando la pandemia de COVID-19 para renovar un estado de emergencia que sentencia a cinco años de prisión a quienes difundan noticias falsas u obstruyan la respuesta del estado a la crisis. Esta nueva ley le permite al primer ministro dictar decretos de forma indefinida.

En la transición de la respuesta hacia la recuperación y más allá, será necesario centrar la atención en profundizar las reformas institucionales y en reempoderar a los ciudadanos, revirtiendo las restricciones en las libertades cívicas y los nuevos mecanismos de supervisión que se han implementado para luchar contra la pandemia pero que podrían quedar instalados en el largo plazo.

Han surgido dos reformas clave que deben ser impulsadas para reempoderar a los ciudadanos tras la crisis del COVID-19: la restauración de las libertades cívicas y la supervisión independiente y el repliegue de la vigilancia estatal.

Restauración de las libertades cívicas y la supervisión independiente: una tendencia que ha surgido como parte de la respuesta a COVID-19 es el control a la libre expresión y los medios, bajo el pretexto de combatir la desinformación sobre el virus. Otro riesgo importante es que los gobiernos pueden restringir las reuniones públicas para combatir las protestas contra el gobierno.

Incluso en un contexto en el que los gobiernos declaran estados de emergencia, debe protegerse el ambiente que permite a los funcionarios rendir cuentas. Si queremos crear sociedades que tienen la capacidad de responder a un desastre, tenemos que proteger a quienes hablan la verdad, a quienes presentan denuncias y a las instituciones encargadas de la supervisión de procesos. Además, debemos asegurar que los científicos y expertos tengan la oportunidad de comunicarse con las instituciones y con los ciudadanos. Los medios de comunicación independientes son fundamentales para asegurar que los gobiernos rindan cuentas, pero ellos también han sufrido recortes y debilitados durante la pandemia. Es importante proteger el acceso a la información para asegurar la supervisión y la rendición de cuentas.

Por ello, es fundamental que los ciudadanos y la sociedad civil exijan a sus gobiernos que definan cuál será el periodo de tiempo tras el cual el espacio cívico será restaurado. Incluso antes de la pandemia, para OGP era una prioridad luchar contra el cierre del espacio cívico: proteger y fortalecer los derechos de expresión, asociación y asamblea y la capacidad de los periodistas y activistas de operar como intermediarios y guardianes. Algunos ejemplos de países de OGP que están protegiendo o fortaleciendo al espacio cívico:

- En Corea del Sur, el gobierno invitó a millones de ciudadanos a Gwanghwamun Square en donde una serie de protestas había derrocado al régimen anterior en 2017, pidiéndoles que propusieran políticas para responder a sus necesidades. El gobierno ha seguido impulsando esfuerzos para permitir que los espacios públicos estén abiertos a protestas.

- En un contexto en el que muchos periodistas han sido acosados y asesinados en todo el mundo, Croacia se comprometió a fortalecer los mecanismos de protección a periodistas y Mongolia se comprometió a fortalecer la independencia de los medios.

- Estonia desarrolló una estrategia nacional de participación ciudadana y desarrolló las capacidades de la sociedad civil para promover su participación en el diseño de políticas.

Aunque estos ejemplos son prometedores, son demasiado pocos y demasiado aislados. Éstos deben ser escalados, en particular en un contexto de cierre del espacio cívico como respuesta al COVID-19.