By Joseph Foti, Paula Pérez, Christina Socci, and Dieter Zinnbauer

in collaboration with The B Team

Overview

The Business Case for Open Government

In 2011, reformers—including government ministers, mayors, parliamentarians, justices, journalists, and activists—launched the Open Government Partnership (OGP). Through the Partnership, currently made up of 75 countries and 105 local members that promote the values of transparency, participation, and public accountability, a diverse set of stakeholders are working to change how governments serve citizens.

Business has always been a critical part of this global community and is a key partner in driving forward these changes. This understanding is reflected in the 2023–2028 OGP strategy, which recognizes that business has an important role to play, particularly in tackling some of the world’s most pressing, interconnected challenges: climate change, corruption, and digital governance.

Though businesses have engaged with other actors throughout the Partnership’s history, the time is right to increase their engagement and commit to supporting open government reforms. The following analysis makes the case for why the private sector should care about open government, how it already supports open government reforms worldwide, and new ways forward for collaboration.

A Diverse, Vital Sector

Promoting a level playing field for companies, streamlining procurement processes, and advancing environmental, social and governance (ESG) investment and reporting standards are all areas where business has been engaging with open government principles worldwide. Business-led reforms directly address these issues—such as opening up contracting processes and lobbying data—by making public sector data more accessible.

The private sector has always been a part of the OGP community. The earliest action plans brought in business as implementation partners of commitments, members of multi-stakeholder processes, and champions of transparency reform.

Now, after a decade of experience, the open government community can begin to tell the story of why and how business engages with open government reform. In collaboration with The B Team, OGP brings together a few cases demonstrating why different businesses decided to engage in more open and collaborative approaches to supporting government actions at the country and local levels.

This web resource has four parts:

- Open business is good business. A review of how private sector interests intersect with open government reforms.

- How business participates in the OGP platform. An exploration of how the private sector has participated in OGP overall.

- OGP commitments most relevant to business. An overview of what commitments affecting the private sector have been carried out in OGP.

- Case studies: Business interests in open government. Three short case studies on how the private sector has helped promote open government:

- a. [Anti-corruption] How Nigeria is Building Private Sector Buy-in for Beneficial Ownership Transparency

- b. [Democratic Freedom] How Business Can Protect Human Rights

- [Lobbying] Why Business is Advancing Lobbying Reforms in Europe

The Open Government Partnership Support Unit worked on this paper in close coordination with The B Team, which contributed to the development of the concept and drafting the content. As a long-standing supporter of the Partnership, The B Team is a global collective of business and civil society leaders advocating for systems change and new corporate norms. This includes leadership change to enhance civic space and civil rights, responsible corporate engagement in government, and corporate transparency (including beneficial ownership transparency), in line with OGP values. Looking ahead, OGP and The B Team will continue to advance enhanced business engagement to find multi-stakeholder, open government solutions to the most pressing challenges facing the world today.

Open Business is Good Business

The private sector has many interests in the work of the OGP community and open governance in general. Business actors are often in the unique position to play many roles to help foster and sustain open governance around the world, as demonstrated below.

- As co-implementers: First, the private sector is a key partner in implementing and innovating new open government reforms. For example, the private sector often receives government contracts to carry out open government reforms. This may include building online tools, helping facilitate public dialogue, carrying out audits, or providing technical assistance to courts to make justice more accessible. In addition, in the context of public-private partnerships and open contracting principles, firms responsible for building and operating public programs and works will often have to meet the responsibilities of stakeholder engagement and will have to meet public accounting requirements. For example, the Ukrainian company YouControl has been active in the OGP community, working to make beneficial ownership information more transparent. YouControl has not only helped assess and suggest a new process to verify beneficial owners in Ukraine as part of the country’s 2021–2022 action plan, but also developed a portal to search for sanctioned Russian and Belarusian companies. To date, 12,000 people have been scanned to reveal the connections between high-ranking officials and offshore companies worldwide.

- As infomediaries: Most citizens do not consume government information directly. They rely on interpreters. Most notably, this is the media, but it may also include private think tanks, business intelligence organizations, or law firms. These “infomediaries” often turn technical information and data into information that is easier to understand and amplify opportunities for public input.

- As gatekeepers: Many private sector companies have enabling or gatekeeping roles with regard to corruption in particular. Banks, law firms, art dealers, real estate and luxury goods agents, auditors, consulting firms, and communications agencies can act as enablers of corruption or as bulwarks against that corruption. Lax implementation of safeguards can allow corrupt practices to thrive and autocrats to launder money away from investments in their country to luxurious destinations in Europe, North America, and the Middle East. While many governments require banks to carry out due diligence on suspicious activity, many industries only voluntarily apply such standards.

- As organized interests: The private sector is often represented by different industry and professional groups. These groups regularly use open government practices, such as open parliamentary processes, lobbying, and open regulatory processes to inform and observe policy making. They also use accountability institutions, like the court system, to resolve issues. Increasingly, such industry associations and professional lobbying associations are advocating for making data on lobbying and participation more transparent and bringing decision-making out of the shadows. (See the case study on Germany, for example.)

- As users of open government data: In countries such as the United Kingdom and Norway, OGP action plans have explicitly sought to stimulate new businesses using open government data. Businesses have explicitly sought to use open government data, building on efforts to innovate new ways of doing business. This might include health data, transit data, or educational data. Increasingly, open science and open educational resources have become areas of interest.

- As regulated entities: The private sector can also contribute to open government reforms in the role of regulated entities. In Nigeria, as the first case shows, compliance officers in the extractive industries supported regulation efforts for the country’s new company beneficial ownership registry. As the entities subject to regulation, their buy-in contributed to the success of the initiative. As regulated entities, private sector organizations have the duty and ability to collect and disclose the data necessary to implement open government reforms.

- As standard setters: In a standard-setting role, businesses can choose to shape better regulations for lobbying that can prove beneficial to them and society at large. The third case study on lobbying reforms in Germany and Spain provides a good example of how the private sector can proactively and positively set new standards, particularly for business-politics relationships. In extractive industries and climate change response, standard-setters (such as bond ratings agencies) have increasing power to persuade governments to be more transparent and democratic, especially where that results in lower lending rates or more predictable financial behavior.

How Business Participates in the OGP Platform

Beyond having a general stake in the success of open government, the private sector is also actively participating in reforms to open up government in different ways. This differs widely by country.

Private sector actors have been part of the OGP multi-stakeholder forums on many occasions. These forums are structured processes—usually biennial—by which non-state actors (civil society, the public, the private sector, etc.) can participate in dialogue with governments to co-create open government reforms through an action plan.

Participation in OGP also comes in the role of acting as implementers of action plan commitments. Countries and localities that are members of OGP commit to concrete reforms through periodic action plans that are then independently assessed by a separate entity within OGP. There are dozens of examples, such as municipal waste management in Iași, Romania, or the numerous forms of cooperation around open contracting, including processes with woman-owned businesses, in Albania. In a similar vein, the private sector also participates in monitoring the work of OGP. Through the Independent Reporting Mechanism (IRM)—the independent arm of OGP that assesses how countries are advancing on OGP commitments—numerous national researchers are either freelance journalists or part of investigative consortia, teachers at private universities, or law firms specializing in government affairs.

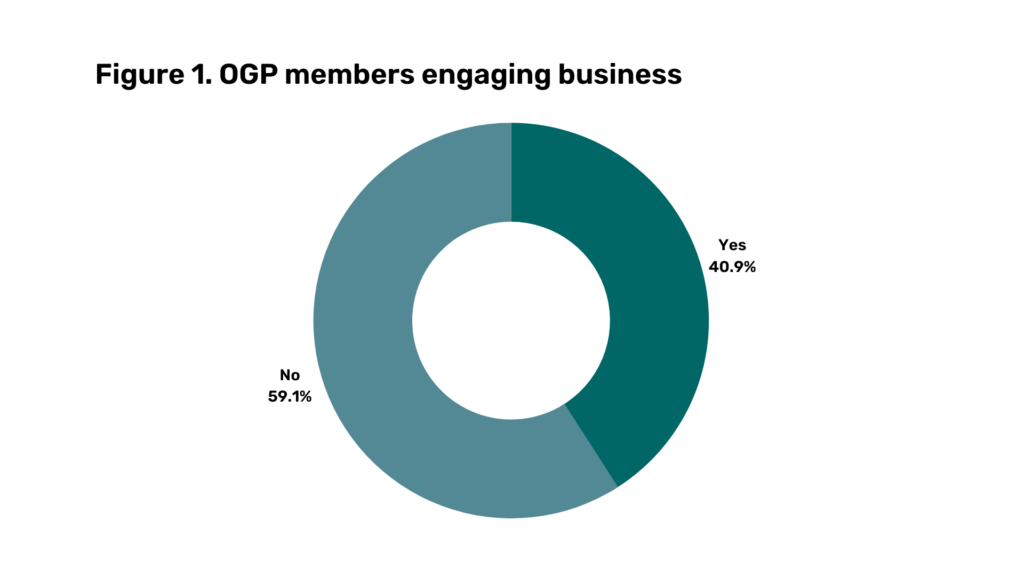

Still, there is more that governments can do to engage private sector actors in open government reforms. Of the 88 OGP members (both local and national) that had data related to their private sector engagement efforts, 36 members (about 40 percent) had private sector participation in designing their action plan commitments, according to OGP tracking data. Here, “engagement” refers to commitments that affect the private sector as regulated entities (e.g., company registries and business regulations) or independent actors (e.g., corporate social responsibility programs). These commitments may also cover public services that concern the business environment, particularly relating to business registration or streamlining regulations to improve the investment climate. The data, shown in Figure 1 below, covers a two-year period from July 2020 to June 2022.

Highlights from private sector participation in multi-stakeholder processes in OGP include:

- Australia has shown the most sustained efforts at incorporating private sector actors into its national processes. ICT Australia, the leading umbrella for government IT contractors, is part of the multi-stakeholder forum.

- Canada has involved law firms focused on privacy in the design of many of its commitments.

- The Philippines has involved local and national businesses for some time, often to oversee its reforms in the fiscal space, but also in beginning to implement the Extractives Industry Transparency Initiative.

- Other countries with occasional active participation of private sector actors include Costa Rica, Croatia, and Honduras.

OGP Commitments Most Relevant to Business

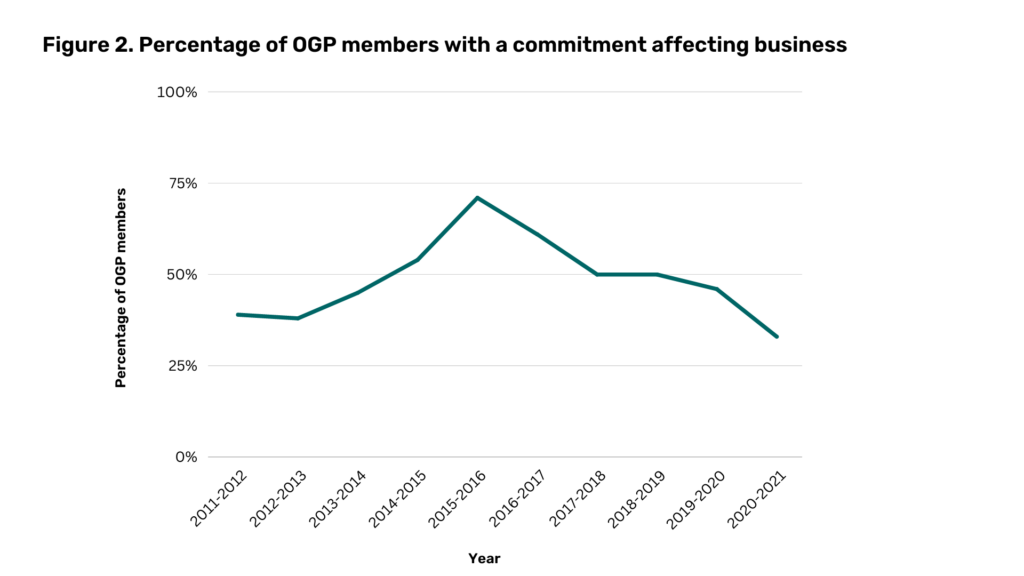

Local and national government members of OGP have laid the foundation to work more closely with the private sector since the founding of the Partnership in 2011. Over the past ten years, members have written 287 commitments that relate to private sector activity, as the graph below illustrates. However, as the graph shows, there has been a decline in the percentage of OGP members that submit commitments affecting business[1] since 2016. While the reasons for this decline are unclear, it is more important than ever for the private sector to step up its engagement with governments to ensure that future reforms take their perspective into account.

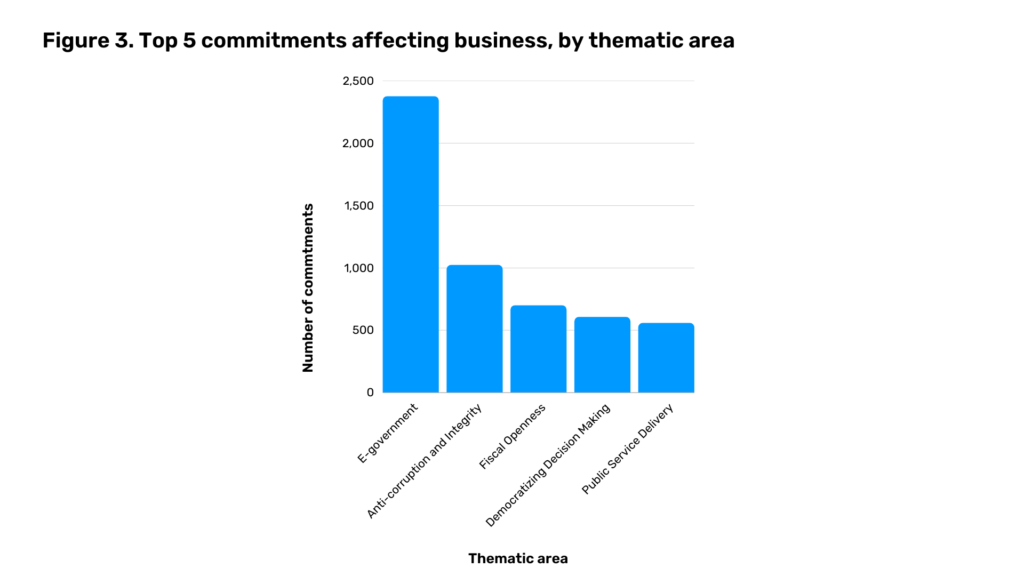

In this same period, OGP members frequently focused on the same themes in their commitments, particularly concerning issues affecting the private sector. Commitments affecting the private sector dealt with numerous policy and practice areas, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Most frequent thematic areas covered in commitments between 2011 and 2022

|

Thematic area and definition |

Number of commitments |

Link to private sector, including the use of public-private partnerships |

|---|---|---|

|

E-government[2] Includes any commitment relevant to:

|

2,376 |

The digital revolution in government may help the government better serve the private sector, increase the transparency of the private sector, or remove opportunities for bribe-paying and other unfair practices. |

|

Anti-corruption and Integrity Includes any commitment relevant to:

|

1,022 |

Reforms to reduce government corruption may reduce opportunities for bribe-paying, but also may increase accountability for private sector actors that either do not play by the rules or take undue actions to bend the rules to their advantage. |

|

Fiscal Openness Includes any commitment relevant to:

|

698 |

Essential for investors in public bonds, private sector partners in public-private partnerships, and businesses interested in leveling the playing field. |

|

Democratizing Decision Making Includes any commitment relevant to:

|

604 |

Businesses have an interest in ensuring that regulations and decisions are made in a transparent, rule-based manner. |

|

Public Service Delivery Includes any commitments relevant to:

|

556 |

The private sector is often a co-implementer of public services and benefits from communities that are healthy, safe, and well-educated. |

OGP members have made notable progress in these thematic areas, with commitments related to the private sector achieving significant early results. Below is a selection of successful regional examples, covering both active participation with business through public-private partnerships and other initiatives, as well as government regulations meant to improve transparency and accountability in business.

Africa and the Middle East

- Sekondi-Takoradi (Ghana) (SEK0004): In the province of Sekondi-Takoradi, the local legislative body (Sekondi-Takoradi Metropolitan Assembly, or STMA) partnered with private sector associations to engage with large businesses, as part of the process of setting the taxes paid to the body each year. As a result, a representative of the Sekondi-Takoradi Chamber of Commerce and Industry (STCCI) now serves on both the Development Planning Sub-committee and the Works Sub-committee. Representatives of STCCI, the Association of Ghana Industries, and other NGOs now serve on the Metropolitan Planning Coordination Unit.

- Kenya (KE0014): This commitment aimed to improve transparency in the public procurement process by introducing beneficial ownership regulations and disclosure policies. To this end, Kenya established the necessary legislative framework to require the public disclosure of supplier or company information, including beneficial ownership. The country also launched a Public Procurement Information Portal, which includes data on tenders, contracts, suppliers, and contract values. The suppliers’ list also includes the supplier or company name, company registration number, business number, registration date, and county of operation.

Americas

- Brazil (BR0079): Brazil updated and consolidated information on companies and individuals who violated public procurement rules in a single National Debarment List to ensure that those on the list could not receive public contracts. The list is also available to the public. The system continues to expand and receive data on sanctions by the executive, legislative, and judiciary branches of government related to both public agents and private entities.

- Colombia (CO0081): Colombia has been able to better identify trends and thematic areas related to women and gender through a public-private partnership to facilitate information sharing on gender data. Specifically, the partnership is between the government, civil society organizations, and academic institutions (including private institutions). This initiative has been particularly relevant to uncovering data on gender-based violence in the country.

Asia and the Pacific

- Indonesia (ID0092): To cut down on illegal palm oil plantations on virgin land to prevent climate change, Indonesia passed a law to create a beneficial ownership registry in the extractive, forestry, and plantation sectors by working with the private sector. This law was the first of its kind in Southeast Asia. The country has since taken steps to make this registry public in its 2020–2022 action plan and will continue to improve the accessibility, verification, and corporate compliance of beneficial ownership data in its 2022–2024 action plan.

- Mongolia(MN0029): In 2016, Mongolia began implementing a new electronic system to collect value-added tax (VAT) that meets international standards. The amount of VAT income collected increased 2.2 times during the first two months of implementation. The conversion from paper receipts to online receipts through this system made it easier for private entities to report to the national tax system.

Europe

- Moldova (MD0061): As part of its 2016–2018 action plan, Moldova passed several laws to create a new e-procurement system, which can be used to award both public and private contracts online. Starting in October 2018, the government required all public procurement entities to use the new system—by November, 27 percent of entities had initiated public procurement processes using the platform. Public procurement competitive awards are now available online through the system, along with data on the procurement process, from planning to award. The government is working to extend the platform to add contracting and implementation functionality.

- United Kingdom (UK0048): In 2016, the United Kingdom became the first country to create a company beneficial ownership registry. Since its creation, the registry has over 5.1 million names of people with significant control over UK-registered companies to date.

Case Studies: Business Interests in Open Government

Learning by Example

How can business apply its interest in open government and the foundation built by OGP members to actually engage in reform? The following case studies address this question by reviewing the concrete steps private sector organizations took to shape public policy decisions. The case studies below draw on related developments from 2020–2023 in OGP countries and businesses working across these relevant open government sectors.

- In the first case, Nigeria illustrates how private sector buy-in is a key ingredient to passing reforms affecting businesses, particularly related to company beneficial ownership transparency.

- In the second case, commitments by Albert Heijn and the Dutch parliament show how human rights impact assessments can better inform companies of human rights violations in business models and solutions to addressing them.

- In the third case, lobbying associations supported the creation of mandatory lobbying registers to ensure greater transparency and public accountability in their work in Germany and Spain.

[Anti-corruption] How Nigeria is Building Private Sector Buy-in for Beneficial Ownership Transparency

Around the world, transparency advocates are working together to promote disclosure of company beneficial ownership information. Doing so requires companies to publish data on the people who own, control, or benefit from companies, including the nature and size of their interests. However, to be successful, private sector buy-in is a key ingredient to making these initiatives reality, as the case of Nigeria shows.

Engaging professionals

The Nigerian Economic Summit Group (NESG), a think tank led by Dr. Tayo Aduloju, cultivated this buy-in as part of broader efforts led by OGP and other stakeholders to prioritize beneficial ownership transparency commitments. Specifically, NESG hosted discussions with members of the private sector in dialogue about their concerns before the beneficial ownership registry law was passed in 2020. This lessened corporate opposition during public hearings later on.

NESG focused discussions on professions that dealt most directly with corporate compliance risk. Specifically, NESG spoke with company secretaries and lawyers, two groups that work on corporate legal compliance, to explain the legal implications of the registry and how it could be helpful for companies in the long run. By first addressing the experts’ concerns, NESG gave the company representatives the tools they needed to convince executives to support the law.

As a result of these discussions, as well as other advocacy efforts, private sector companies in extractive industries and professional associations, like the Nigerian Bar Association, supported the creation of a beneficial ownership registry.

More than corruption

Dr. Aduloju knows that this approach can deliver even more. He specifically sees a need to increase private sector supply chain transparency and public accountability. Corruption in the supply chain is currently hard to detect, Dr. Aduloju says. But this corruption has real effects. Lack of transparency hides serious abuses of children’s rights, women’s rights, and labor rights in general.

By building on the goodwill generated by the company dialogues on beneficial ownership, he believes there is “a lot of opportunity for social, political and social cultural transformation that simply cannot happen any other way… If we were able to see more deeply into the supply chains, [then] that will create a true win-win relationship for producers, consumers, citizens [and] employees.”

Policies to end anonymous companies are becoming more popular thanks to the work of organizations like NESG. But lone actors cannot enact reforms. One-time opponents can become allies, and people standing on the sidelines can become engaged. This may be through private sector participation in OGP processes overall or through specific reforms, as in the case of beneficial ownership reform in Nigeria. By joining early conversations, private sector actors can have a say in shaping and contributing to essential reforms.

[Democratic Freedom] How Business Can Protect Human Rights

Businesses have a critical role in protecting not only the rights and well-being of customers, but also those of the workers throughout their supply chains. Too often, the process of getting a product from raw materials to finished goods does not consider the potential or actual harms the workers face at each step of sourcing and production. To address this, companies have begun assessing their practices to ensure that they respect and protect human rights and good government. One such example is from Dutch grocery store Albert Heijn.

Evaluating risk and mitigating harm

Companies are responsible for ensuring that their products are not used to violate human rights, particularly through their supply chains. This is especially a concern in the supermarket industry, as Oxfam’s ongoing Behind the Barcode campaign has shown. Since its launch in 2018, the campaign has revealed abuses in the policies and practices of large supermarket chains and challenged companies to do better.

In 2019, Albert Heijn responded to the call for change by committing to undertake six human rights impact assessments per year in collaboration with key stakeholders, such as local workers, non-government organizations, and trade unions. The assessments will focus on low-wage work, farmer income, and women’s rights in their supply chains, focusing on their high-risk agricultural supply chain. The explicit focus on women’s rights is notable, given the gender-specific challenges women disproportionately face, particularly in agriculture, such as harassment and exploitation.

The Dutch parliament has also recognized the need for greater human rights considerations in the country’s legal framework, which would build upon the voluntary actions of specific companies by expanding protections for all. In 2021, lawmakers first introduced legislation to mandate certain human rights due diligence practices by businesses, with an amended bill submitted to the House of Representatives in November 2022.

Mainstreaming human rights assessments

This commitment sets important precedents. Business not only has an ability to support key open governance values of civic participation, transparency, and accountability—it also has the unique responsibility to do so.

A human rights impact assessment is a first step to respect and protect human rights. To maximize these connections, businesses can strengthen their positive impact by partnering with organizations like OGP to build on the foundation of these promising practices.

[Lobbying] Why Business is Advancing Lobbying Reforms in Europe

In a democracy, everybody needs to be able to observe and inform the policy making process. But when conversations take place behind closed doors, as is too often the case, the public cannot tell who is influencing decisions and whether it matters. Just as important is being able to tell if money or favors change hands.

As former Unilever CEO Paul Polman explained in a 2021 article for the Harvard Business Review, “We cannot let bought authority continue to overrule all else. It is time for CEOs to step up as moral leaders. This will require acting with transparency, integrity and a view to lasting impact…This is what it will take to help save our democracy.”

Unfortunately, recent research from the United Nations Principles for Responsible Investment (UN PRI) network shows that many private sector lobbies continue to exploit loopholes meant to require disclosures about their activities, especially in light of lax regulations across different jurisdictions. However, some lobbying associations in Europe are taking a different approach.

For years, large industrial groups in Germany had opposed lobbying transparency reforms. But in 2019, some of Germany’s most powerful business lobbies, including the Chemical Industry Association and the Federal Association of German Industries, decided to take proactive action to push for regulation. They teamed up with civil society organizations to form the Alliance for Lobbying Transparency. The Alliance has since been a very vocal and influential supporter of legislative efforts to establish a mandatory lobbying register.

In 2020, predicting the shift in policy, Timo Lange, campaigner and director of LobbyControl, told Norbert Theihs of the Verband der Chemischen Industrie, “The wind has changed, and I think that has something to do with your activities in the chemical industry.”[3]

Indeed, in March 2021, the coalition government finally agreed to establish this register—the law took effect in January 2022.

Changing corporate demand

Why exactly has this change happened? And what are the lessons for other countries?

Part of this has to do with a changing bottom line for companies. Consumers, employees, shareholders, and policy makers are increasingly looking to the private sector to play a key leadership role in solving the climate crisis and protecting democracy. That includes disclosing their political activity.

Some elements of this are reputation management and higher expectations from consumers and shareholders who want to know that their company is following the law and acting ethically. Investors are also moving to a hands-on approach when it comes to the lobbying activities of their portfolio companies. They are increasingly applying transparent, well-governed, and purpose-aligned corporate political activity as a screening factor or as an issue for direct engagement with management.

Responsible conduct in political engagement is not just an issue for large businesses. Smaller companies gain confidence when bigger players, who tend to vastly outspend them, commit to transparent, responsible conduct. It is not a surprise that the 4,000-member strong German association of family entrepreneurs has come out in support of more lobbying transparency in the country and joined the larger industry initiative.

Local-level reform in Spain

The case of Spain also shows why members of the private sector are supporting reforms to improve transparency of lobbying and access to officials.

As Diego Bayón Mendoza, the Director of Advocacy and Public Awareness at Harmon Corporate Affairs and a board member of the Spanish Association of Professionals of Institutional Relations, explained in a 2021 OGP event, this transparency benefits them as well. He said, “We believe the private sector will be better able to anticipate policy developments on upcoming regulations, assessing the potential impact on business.”

Madrid, in particular, has led the country’s progress in advancing lobbying reforms. In its 2017 OGP action plan, the capital created a mandatory lobbying registry to disclose any public meetings with the city council. The registry, available publicly online, allows the public to subscribe for alerts, view official calendars, and request meetings with their representatives. In making the registry mandatory, Madrid is leading the way for other local and national governments to require participation in such registries, a key ingredient to ensuring their effectiveness. As of this writing, over 850 lobbyists have registered.

The road ahead

Despite this progress, an enormous amount of work remains. A recent OGP report, which maps the broken links between people and data allowing political corruption to flourish, shows that three-quarters of OGP members do not have lobbying laws. Governments may not clearly define who counts as “lobbyists,” making tracking and regulating their activity even more difficult.

However, as these examples show, innovation in lobbying regulation can achieve much with basic guardrails to ensure the disclosure of meetings, money, and influence. With the support of the OGP framework, governments and lobbyists can rework their relationship to bring more transparency, public accountability, and equal representation into the business-politics relationship.