Why opening company ownership data is good for business

In a couple of days, the British Prime Minister David Cameron will be speaking at the Open Government PartnershipThe Open Government Partnership (OGP) is a multi-stakeholder initiative focused on improving government transparency, ensuring opportunities for citizen participation in public matters, and strengthen... More event in London, and the question is: will he follow through on his statement made at the G8 Trade, TaxPlacing transparency, accountability, and participation at the center of tax policy can ensure that burdens are distributed equitably across society. Technical specifications: Commitments related to c... and TransparencyAccording to OGP’s Articles of Governance, transparency occurs when “government-held information (including on activities and decisions) is open, comprehensive, timely, freely available to the pub... More event to ‘push for more transparency on who owns companies’, specifically showing leadership by tackling the issue in the UK.

There’s a compelling case why this is necessary, to tackle money-laundering, organised crime, stolen assets, sanctions-busting and other criminal activities, and it’s clear that the use of corporate vehicles for these activities is becoming so widespread that it can only be tackled by a public register of who owns and controls companies.

However, there’s a further reason why this is so important, and goes back to the fundamentals of why we have companies in the first place, back in fact to the beginnings of the systematic creation of companies in the 19th century: it is essential to give “the greatest publicity to the affairs of… companies, that everyone may know on what grounds he is dealing”.

That quote is by Robert Lowe, Deputy of the Board of Trade and later Chancellor of the Exchequer, introducing the 1856 Companies Act into the British parliament (Lowe is considered by some to be the father of the modern company).

Companies are not people – living, breathing things with unalienable rights – but artificial legal constructs, created by the state and given legal personality, which means even though they don’t consist of atoms like you or me and can’t be jailed, they have the ability to sign contracts, raise money, have assets and liabilities, and employ people.

In the UK, originally companies were created by an Act of Parliament, or by Royal Charter, and the idea that they could created on demand was a fairly contentious one at the time. The thought was that by allowing this, there would be more innovation, more investment – in short society would benefit. But that last point is a critical one – the justification behind them is not for the benefit of companies, or their owners, but the benefit of wider society.

If you think creating a legal personality is strange, the idea of limited liability is even more so, as what it means is that when the liabilities (debts) of a entity exceed its assets (the money the shareholders have put in and anything that’s been accrued since then), then the people that bear the shortfall are not the shareholders or the managers (who benefited from the profits), but the suppliers (who don’t get paid), the customers (who don’t get the goods they’ve paid for), the employees (who don’t get wages), and wider society (lost tax, bailed-out pension funds, benefits, cleanup of polluted sites, etc).

Critical to this idea is the ability to take an informed decision about whether you want to do business with the company, work for it, or, in the case of the state, ensure that it does not engage in fraud or other criminal activities – in other words, knowing who you are dealing with. That means the knowing the shareholders and directors.

Were every company register to do what the New Zealand company register does, for example, and make the shareholder and director data available, much of the problem would be in theory be tackled (and that’s why OpenCorporates created the Open Company Data Index in partnership with the World Bank Institute, to measure access to the basic information about companies from company registers). Most SMEs, after all, are straightforward structures where the shareholders are the same as the directors and they hold the shares in their own names.

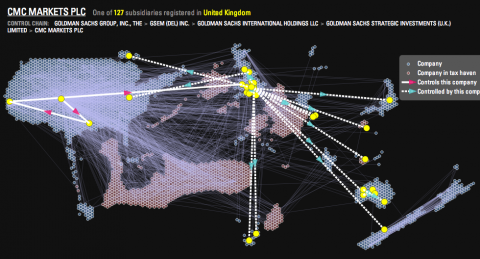

However, for some, particular those that want to obfuscate this information, there are many opportunities to do so these days – through nominee directors and shareholders, offshore entities, and complex networks of obscure company structures the rules. Whether it’s to get around sanctions, launder drug money, enable bribery and corruption, or simply to game regulatory requirements, there are plenty of incentives for doing so, all of them toxic for good business.

That’s where beneficial ownershipDisclosing beneficial owners — those who ultimately control or profit from a business — is essential for combating corruption, stemming illicit financial flows, and fighting tax evasion. Technical... More comes in. It’s simply a fancy way to say that you need to disclose where the shareholding data doesn’t show the true picture.

So we hope for the sake of good business everywhere David Cameron will take the opportunity of the Open Government Partnership meeting in London, and announce that he will take inspiration from Robert Lowe, and truly open up company ownership, for the benefit not just of civil society around the world, but because it’s good business too.

Image credit: view of a corporate network via opencorporates.com