Ukraine’s Inspiring Journey in the Open Government Partnership

This publication was produced with the financial support of the European Union. Its contents are the sole responsibility of the Open Government PartnershipThe Open Government Partnership (OGP) is a multi-stakeholder initiative focused on improving government transparency, ensuring opportunities for citizen participation in public matters, and strengthen... More and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union.

Чтобы прочитать этот на русском языке, нажмите здесь.

The Russian war on Ukraine is taking place at many levels. The first, on the physical battleground, is resulting in daily devastation and loss of human life and physical infrastructure at a scale that many of us cannot fathom. For others, it is more familiar and a reminder that multilateralism and global peace remain unfulfilled ideals. The second, happening online and in the media, is a battle between truth and dis- and misinformation. Underlying both of these, is a war between competing ideologies of the relationship between a state and its peoples. The contestation between autocracy and democracy, between closed and open societies.

People across the world have been watching the response of the Ukrainian people with a mix of awe and inspiration, heartbreak and despair, as they fight back heroically. But this is not the first time the country and its people have inspired the world by fighting against the odds. Ukraine’s journey in the Open Government Partnership, especially the reforms undertaken after the 2014 ‘Revolution of Dignity’, also known as the ‘Maidan Revolution’ has inspired action across the Partnership. What follows is a chronicle of the reforms Ukraine has undertaken in its ten years as an OGP member, and what has been so tragically interrupted by the war.

Turning Citizen Discontent into Collective Action

The Maidan Revolution was spurred by protests against what citizens perceived as grand corruption and abuse of power, a desire for closer ties with the European Union, and their rejection of cronyism and injustice as an inevitability of public life.

But this is not the first time the country and its people have inspired the world by fighting against the odds.

Ukraine joined OGP before Maidan, in 2011, and has adopted five open government action plans since then. The first action plan (2012-2013), employed traditional consultations with established civil society groups specializing in governance issues, much like other OGP countries at the time. It included measures to improve public services; introduce e-petitions systems; develop or update laws on public participationGiving citizens opportunities to provide input into government decision-making leads to more effective governance, improved public service delivery, and more equitable outcomes. Technical specificatio..., access to information, and anti-corruption; and prepare Ukraine for implementation of the Extractive Industry TransparencyAccording to OGP’s Articles of Governance, transparency occurs when “government-held information (including on activities and decisions) is open, comprehensive, timely, freely available to the pub... More Initiative (EITI) standards.

Ukraine’s second OGP action plan (2014-2015) was developed in the immediate aftermath of the Revolution, when the post-Maidan government was pledging sweeping reforms. The plan included ambitious reforms on anti-corruption and decentralization, clearly responding to some of the issues that had driven citizens to the streets with concrete policy action. Notable achievements of that action plan included opening up access to communist-era archives, which granted public access to secretly kept documents of the Soviet regime and enforced the right to truth. More than 87,000 individuals accessed the archive in 2015 alone. The plan also included commitments which resulted in the publication of Ukraine’s first national EITI report, which, for the first time, disclosed information about key Ukrainian oil and gas fields, license holders, production volumes, as well as the payments companies made to budgets at all levels. In 2016, Ukraine launched the flagship electronic asset disclosure system creating an unprecedented level of transparency of public officials’ assets. It drew enormous public attention, resulted in a number of media investigations, and helped create greater public demand for accountability. The newly created National Anti-Corruption Bureau (NABU) started several investigations into unjustified wealth based on the declarations.

The reinvigorated OGP process in post-Maidan Ukraine also kick-started important open dataBy opening up data and making it sharable and reusable, governments can enable informed debate, better decision making, and the development of innovative new services. Technical specifications: Polici... initiatives, which set the ground for sectoral transparency reforms in the following years. The law on open data established the basic legal framework for public access to government-held datasets and allowed for their free reuse. This triggered the creation of a myriad of tools for tracking government spending and facilitating its public oversight. Several public institutions began publishing key datasets, including a number of public registers by the Ministry of JusticeTo address barriers that prevent citizens from having their justice needs met, OGP participating governments are working to expand transparency, accountability, and inclusion into all systems of justi... and tax-related datasets by the TaxPlacing transparency, accountability, and participation at the center of tax policy can ensure that burdens are distributed equitably across society. Technical specifications: Commitments related to c... Administration. Civil society worked hand in hand with government agencies to develop user-friendly IT tools for tracking using available government open data.

Pioneering Anti-Corruption Reforms

When OGP’s founders came together to design the Partnership in 2011, they firmly believed that good ideas on open government could come from anywhere, sometimes from places many would least expect. They also believed that countries could have different starting points but still be ambitious in their own contexts. Ukraine stands as a testament to these foundational principles as a pioneer of many innovative anti-corruption reforms.

Ukraine’s third OGP action plan (2016-2018) introduced outstanding changes in the extractives sector and online tools for monitoring public contracting. ProZorro and DoZorro have gone on to become household names in the public procurement and open governance universe – the most powerful examples of how citizens can hold their governments accountable and a strong case for why open contracting is good for governments and good for business. Just in the first two years since its launch, ProZorro saved the government an estimated US$1 billion USD, 80 percent of businesses surveyed reported reduced corruption from the use of the platform and the number of new businesses – including SMEs – bidding for contracts increased by 50 percent. Thanks to DoZorro, over three years, violations were registered in over 30,000 tenders with an estimated value of US$4 billion. In some cases, sanctions and criminal charges were issued.

It’s not surprising that ProZorro has received recognition from many different places, including OGP’s 2016 Open Government Award. In 2015, Ukraine became the first country in the world to launch a public register of beneficial owners to tackle hidden ownership of companies and expose dirty money. This work was also taken forward in subsequent OGP action plans, and civil society has pushed for continuous improvements, including on data verifiability and linking beneficial ownership and public procurement data. (Read OpenOwnership’s case study on the early impacts of beneficial ownership in Ukraine here.)

Notable achievements in Ukraine’s fourth OGP action plan (2018-2020) included greater transparency in public budgets and the sale and lease of public property and assets and continued progress on opening up public procurement. Government and civil society reformers working on ProZorro showed no signs of wanting to rest on previous laurels. ProZorro.Sale turned abandoned assets into productive ones, opening business access to investment opportunities and allowing civil society organizations to monitor the integrity of the transactions, thereby earning more trust in the privatization process. Prozorro.Sale provides information about every public asset available for rent and a clear way to bid online. More than 10,000 auctions had been held by late 2021, generating revenues of more than US$37 million per year to budgets. ProZorro.Sale went on to win the 2021 OGP Impact Award.

In their 2018-2020 action plan, Ukraine pursued alignments between open government and the Sustainable Development GoalsOGP countries are experimenting with open government innovations to accelerate progress on the Sustainable Development Goals, particularly SDG 16+ which includes peaceful, just and inclusive societies... (SDGs). Commitments included: opening the National RepositoryAccess to relevant information is essential for enabling participation and ensuring accountability throughout the OGP process. An OGP repository is an online centralized website, webpage, platform or ... of Academic Texts (SDG 4), ensuring free access for citizens to environmental information (SDG 11), implementing the Extractive IndustriesApplying open government values of transparency, participation, and accountability to extractive industries can decrease corruption, safeguard community interests and needs, and support environmental ... Transparency Initiative and the Transparency Construction Initiative online (SDG 9), and creating an online platform for cooperation between civil society and the state (SDG 16).

Many of these reforms originated outside the OGP platform. These anti-corruption reforms were a fundamental pillar of the nation building and democratic project post-Maidan, in recognition of how dirty money – fuelled by domestic and transnational corruption – weakened institutions and gains made through other reforms. Both government and civil society smartly used OGP, other international initiatives, and their bilateral and multilateral partners to further ambitionAccording to OGP’s Articles of Governance, OGP commitments should “stretch government practice beyond its current baseline with respect to key areas of open government.” Ambition captures the po... and collaboration. Reformers also used these global networks to draw international support and resourcing and maintain pressure for this work to continue. Just as importantly, they generously shared their lessons and expertise with their peers across the globe.

None of this is to suggest that there weren’t real and serious domestic problems in Ukraine before the war. The fight against corruption was nowhere close to being won, many who beat the system still enjoyed impunity, and political rivalries and vested interests regularly reared their ugly heads, pushing back against the progress being made. But the desire for change and the willingness to fight for it, across different sections of society, was real and palpable.

Khmelnytskyi’s team at the final OGP action planAction plans are at the core of a government’s participation in OGP. They are the product of a co-creation process in which government and civil society jointly develop commitments to open governmen... co-creation event in 2021.PHOTO: Credit: Tetiana Rohoza

Localizing Open Governance and Democracy

The Maidan Revolution also ushered in decentralization reforms in the country – with commitments on improving budgeting, e-governance and public services at the local level across several OGP action plan cycles. Vinnytsia, Khmelnytskyi and Ternopil joined OGP Local in 2020. Vinnytsia planned to develop regulations on public consultations to strengthen their governance systems. Khmelnytskyi included a commitment to develop a Green City Action Plan to establish a green vision for the city and engage citizens in its implementation, which was recognized in the inaugural 2021 OGP Local Innovation Awards. Remarkably Ternopil turned in its action plan just a few days before the war began.

There were expectations that many more would join their ranks in 2022, including Mariupol, which had been making big strides in open contracting and transparency before it became the site of the worst horrors of the Russian war.

Ukrainian reformers have been working to connect national and local open government work for years. For example, in 2020 national and local authorities launched a platform for National-Local Consultation on Open Government. Ukraine had the second highest number of events during the 2021 Open Gov Week, with many outside the center of national government in Kyiv.

Ukraine’s experiments with local democracy went well beyond what it did in OGP and started shifting power to local communities, including by significant devolution of budget and taxation authority to local governments in a relatively short span of time. It is unsurprising therefore that mayors and residents in towns of all shapes and sizes have emerged as heroes of the Ukrainian resistance.

It is unsurprising therefore that mayors and residents in towns of all shapes and sizes have emerged as heroes of the Ukrainian resistance.

A Vibrant Ecosystem of Reformers

While the Ukrainian open gov community has inspired OGP members through their reforms, they’ve also been a role model for a strong government-civil society dynamic. They’ve shown how civil society can work hand-in-hand with reformers in government to effect change, even as it plays its role of keeping governments honest and accountable. In the same vein, reformers in government showed their peers what it means to take bold measures to break away from ‘business-as-usual’ in governance. Both government and civil society worked together to improve the co-creation of OGP plans over the years. Lessons learned from their approach can be found here.

Ukraine was among the first cohort of countries in OGP to work on strengthening parliamentary engagement in the open government agenda, to secure the legislative support needed to enable many of the aforementioned reforms, and strengthen parliamentary oversight. While these efforts faced challenges in recent years – including attempts to dilute earlier gains by the Verkhovna Rada – Ukraine was one of the early adopters of an Open State approach, whereby all state institutions and independent agencies participate in advancing open government. Similarly, private sectorGovernments are working to open private sector practices as well — including through beneficial ownership transparency, open contracting, and regulating environmental standards. Technical specificat... More engagement – aspirational, but difficult to achieve in many OGP countries – was critical to many of the reforms highlighted earlier like ProZorro and infrastructure transparency. The government, civil society and the private sector, co-created and co-implemented these reforms.

In Ukraine, OGP has never been about a static plan but rather a dynamic dialogue that constantly evolved through the years.

It wasn’t always easy. While civil society and government worked together constructively on specific reforms and recognized each others’ contributions, civil society also did not hesitate to call the government out when it fell short on delivering. When Ukraine’s first OGP action plan didn’t include many of civil society’s asks, civil society strategically and collectively responded with one of the first OGP civil society shadow action plans. In response, the government reopened the action plan process and its contents. There have been incidents of government crackdowns on civil society, particularly those working on anti-corruption, but also dialogues on how to improve the operating environment.

In Ukraine, OGP has never been about a static plan but rather a dynamic dialogue that constantly evolved through the years.

Looking Ahead

No one can tell for sure when and how this war ends and how many more innocent lives will be meaninglessly sacrificed in the process. What we know for sure is what is at stake.

It is hard to imagine that in early February 2022, even as many feared what might have been coming, government and civil society involved in open government and OGP were very much still talking about future plans. They were implementing their fifth OGP action plan (2020-2022). With support from the EU for Integrity Programme, Transparency International Ukraine was developing a business intelligence application for conducting a comprehensive analysis of awarding and completion of public procurement contracts allowing activists, public procurement experts, and regulatory and controlling bodies to identify gaps in Prozorro. Infrastructure Transparency Initiative (CoST Ukraine) was building an online platform “Ukrainian Social Infrastructure” to support proactive citizens in monitoring the construction of social infrastructure projects. YouContol LLC was working with the State Chancellery, implementing agencies and civil society on an audit of existing registries to enable better verification of beneficial ownershipDisclosing beneficial owners — those who ultimately control or profit from a business — is essential for combating corruption, stemming illicit financial flows, and fighting tax evasion. Technical... More data. And these are just a few examples, among many.

Ukraine’s OGP government point of contact, Nataliia, and other reformers meet in Kyiv at an IRM event.

Even at this moment, as our friends and colleagues from Ukraine fight for their lives and that of their loved ones, it is remarkable to see how they continue to live by and fight for the principles of open government.

No one can tell for sure when and how this war ends and how many more innocent lives will be meaninglessly sacrificed in the process. What we know for sure is what is at stake. It is not just the reforms but also the lives of the people that drove them and countless others. There are too many reformers to name here without doing injustice to the big, vibrant, active OGP community in the country. Even at this moment, as our friends and colleagues from Ukraine fight for their lives and that of their loved ones, it is remarkable to see how they continue to live by and fight for the principles of open government. Prozorro launched a platform for procurement during the war. Reformers are calling for a Kyiv Marshall Plan to be a model for open government. These are just a few, of many such examples. It is clear that when the rebuilding effort starts, Ukrainian reformers will apply all that they have learned and outdo themselves. For now, they need the support of the international community whose principles they are fighting for. Their asks are unanimous and clear (see: The Kyiv Declaration signed by over 100 civil society organizations).

Quick Facts

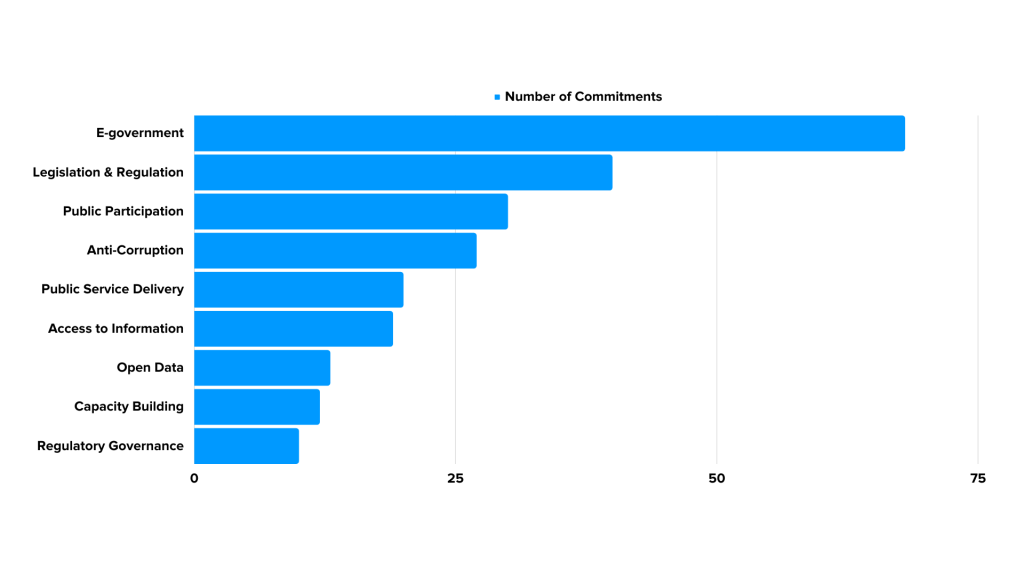

Popular Themes

Comments (1)

Leave a Reply

Related Content

Ukraine

Ukraine’s sixth action plan includes commitments addressing the transparency of and participation in restoration processes, harmonization with European Union (EU) legislation, and restoring access to information. Most commitments will be…

Statement from the Co-Chairs of the OGP Steering Committee on Ukraine

We unequivocally condemn the unjustified and unprovoked attack on Ukraine, a member of the Open Government Partnership...

Statement from the EITI Board Chair and Open Government Partnership Ambassador, Rt Hon. Helen Clark, on the situation in Ukraine

On behalf of the EITI, I express our strong solidarity with our Ukrainian colleagues and stakeholders. We stand with them and offer our firm support during these dreadful times. We…

christian alfaro muirhead Reply

Que venga la paz pronto a Ucrania, es el deseo de toda persona bien nacida. No puede haber otra mirada. Los hermanos Karámzov en Eurasia no pueden permanecer en ese enfrentamiento irracional, fratricida, inhumano. Los medios hacen tremendamente más dolorosa esa guerra en todos los hogares del planeta, en pleno siglo XXI.