Regulatory Governance in the Open Government Partnership

Open Government Partnership | Analytics & Insights Team

World Bank | Global Indicators of Regulatory GovernanceWhen citizens understand and help to shape the rules that govern society, regulations are more effective, business environments are stronger, and levels of corruption are lower. Technical specificatio... Team

When citizens understand and help to shape the rules that govern society, regulations are more effective, business environments are stronger, and levels of corruption are lower. Since the founding of OGP, many members have made commitments to improve regulatory governance. This paper looks at these OGP reforms, together with data from the World Bank’s Global Indicators of Regulatory Governance (GIRG), to achieve the following goals:

- Lay out the basic components of an open regulatory process

- Assess how OGP countries currently fare in implementing those components

- Identify key areas for improvement

- Identify innovations across OGP countries

This paper covers four key areas of regulatory governance where open government and GIRG data collection align: accessing laws and regulations, transparencyAccording to OGP’s Articles of Governance, transparency occurs when “government-held information (including on activities and decisions) is open, comprehensive, timely, freely available to the pub... More of rulemaking, public consultations, and challenging regulations (see Table i for more information about these categories). There are of course other areas of regulatory governance that this paper does not address, such as impact assessments and ex-post reviews. This paper includes all 78 OGP countries but does not analyze commitments made by local OGP members given the national-level focus of the GIRG project.

This paper is part OGP’s Global Report campaign, which can be found here.

- Regulatory Governance in the Open Government Partnership – Full Text | PDF

- Lessons from Reformers:

- New Zealand commits to publishing secondary legislation online

- South Africa’s push for open access to legislation

- Albania publishes local government legislation online

- The European Parliament’s Legislative Train

- Estonia shifts from online consultation to co-creation

- Mexico builds a regulatory ecosystem

- The United Kingdom brings in citizens to review regulations

Explore the OGP Regulatory Governance Dashboard for a visual snapshot of how each OGP country is performing according to all of the key indicators of regulatory governance analyzed in this paper.

Contents

Executive Summary

Introduction

1. Accessing Laws and Regulations

Lessons from Reformers: New Zealand commits to publishing secondary legislation online

Lessons from Reformers: South Africa’s push for open access to legislation

Lessons from Reformers: Albania publishes local government legislation online

2. Transparency of Rulemaking

Lessons from Reformers: The European Parliament’s Legislative Train

Lessons from Reformers: Estonia shifts from online consultation to co-creation

3. Public Consultation

Lessons from Reformers: Mexico builds a regulatory ecosystem

4. Challenging Regulations

Lessons from Reformers: The United Kingdom brings in citizens to review regulations

Annex: Reforms in Practice

How to Use This Paper

- Read the key points of the paper: See the “Summary of Findings” for the main points.

- Understand where OGP members stand on regulatory openness: See the “An Overview of Regulatory Governance Across OGP Action Plans” section for an overview of how OGP members perform across all areas of regulatory openness. The four chapters provide more in-depth analysis.

- Learn about strong innovators in the field: See the featured case studies (after chapters 1, 2, and 3) showcasing a strong reform with lessons for other reformers.

- Identify next steps and potential commitments: The start of each chapter includes a maturity model that lists recommendations for future OGP commitments.

- Find examples of reforms from across the world: Reforms showing how governments are implementing steps in the maturity models are highlighted throughout each of the chapters. A subset follows. Other reforms are listed in the “Annex: Reforms in Practice.”

Chapter 1. Accessing Laws and Regulations

- New Zealand: Publishing secondary legislationCreating and passing legislation is one of the most effective ways of ensuring open government reforms have long-lasting effects on government practices. Technical specifications: Act of creating or r... online

- Romania: Providing free and comprehensive access to legislation

- Kenya: Disclosing subnational laws, international treaties, and historical laws

- South Korea: Publishing laws in an easy-to-understand format

- Chile: Reducing language barriers in accessing legal texts

Chapter 2. Transparency of Rulemaking

- Kyrgyz Republic: Building a unified regulatory portal

- Netherlands: Digitizing local and regional regulatory announcements

- South Africa: Publishing annual reports with regulatory developments

- Colombia: Mandating forward regulatory plans

Chapter 3. Public Consultations

- Afghanistan: Consulting local communities on infrastructure projects

- El Salvador: Enabling citizen participationAccording to OGP’s Articles of Governance, citizen participation occurs when “governments seek to mobilize citizens to engage in public debate, provide input, and make contributions that lead to m... More in environmental policy-making

- Croatia: Requiring consultations and reporting on the outcomes

- Latvia: Finding a consensus with civil society in policy development

- Morocco: Raising awareness of participation opportunities at the regional level

Chapter 4. Challenging Regulations

- United Kingdom: Bringing in citizens to review regulations

- Peru: Involving citizens throughout the regulatory life cycle

Good to Know: Defining key terms in regulatory governance

In this paper, regulations are the rules adopted by an executive authority, ministry, or regulatory agency to implement laws enacted by the legislative branch of government. Regulatory provisions are legally binding with respect to officials, individuals, or companies covered by them. Regulations include subordinate legislation, administrative formalities, decrees, circulars, and directives. By extension, the rulemaking process is defined as the process for initiating, drafting, deliberating, and issuing final regulations. As a result, this paper (with the exception of Chapter 1, “Accessing Laws and Regulations”) deals with the enforceable regulatory implementation of laws, rather than with primary laws (passed by the legislative branch of government) themselves.

Table I. Four Areas of Regulatory Governance Studied in This Paper

Global Indicators of Regulatory Governance Topics | Research Questions | |

| Accessing laws and regulations | Do the private sectorGovernments are working to open private sector practices as well — including through beneficial ownership transparency, open contracting, and regulating environmental standards. Technical specificat... More and general public have free and effective access to the entire (official) collection of reliably updated and complete national laws and regulations of a given jurisdiction? |

| Transparency of rulemaking | Are officials systematically obligated to issue timely public notice of proposed changes in regulations and publish proposed texts for public review and comments? |

| Public consultation | Are there minimum standards relating to how, when, and from whom policy-makers seek input on new or amended regulations before issuing final regulations? |

| Challenging regulations | Can citizens challenge the legal validity of a regulationGovernment reformers are developing regulations that enshrine values of transparency, participation, and accountability in government practices. Technical specifications: Act of creating or reforming ... or regulatory provision? Relatedly, can they challenge an action or decision of a regulator pursuant to a regulation? How? |

Executive Summary

When citizens understand and help to shape the rules that govern society, regulations are more effective, business environments are stronger, and levels of corruption are lower. Since the founding of OGP, many members have made commitments to improve regulatory governance. This paper looks at these OGP reforms, together with data from the World Bank’s Global Indicators of Regulatory Governance (GIRG), to achieve the following goals:

- Lay out the basic components of an open regulatory process

- Assess how OGP countries currently fare in implementing those components

- Identify key areas for improvement

- Identify innovations across OGP countries

This paper covers four key areas of regulatory governance where open government and GIRG data collection align: accessing laws and regulations, transparency of rulemaking, public consultations, and challenging regulations (see Table i for more information about these categories). There are of course other areas of regulatory governance that this paper does not address, such as impact assessments and ex-post reviews. This paper includes all 78 OGP countries but does not analyze commitments made by local OGP members given the national-level focus of the GIRG project.

Summary of Findings

In general, OGP reforms have contributed to important results, particularly around civic participation. Nonetheless, more work is needed to engage citizens earlier in the rulemaking process, strengthen accountability mechanisms, and mainstream open regulatory practices across multiple levels of government, particularly in lower-income countries. More specific findings and recommendations for each of the four key areas of regulatory governance studied in this paper follow.

Accessing laws and regulations

- State of play: OGP members are strongest in this area. Most countries make laws and regulations publicly available, although the quality of the information is an issue. Keeping legal databases up to date is also a challenge.

- Recommendations: Maintain a comprehensive, searchable, and free-to-access central website for all existing laws and regulations. Eliminate restrictions on data usage, and ensure regular updates of the information. Ensure disclosure at the local level as well.

Transparency of rulemaking

- State of play: Several countries have made OGP commitments in this area. However, most OGP countries still do not publish forward regulatory plans, particularly in the Americas and Africa, where relevant commitments are generally lacking.

- Recommendations: Publish forward regulatory plans and regulatory drafts on unified portals that enable citizens to provide feedback. Ensure that citizens can follow regulations from development through to adoption.

Public consultations

- State of play: Most OGP members have notice-and-comment systems in place (albeit not all legally enforceable), but many do not provide a reasoned responseOngoing dialogue between stakeholders during the development of an OGP action plan is critical to the plan’s success. Specifically, communicating back to stakeholders the ideas received and decision... to citizen input, much less through dedicated websites.

- Recommendations: Adopt laws that mandate notice-and-comment procedures, set minimum standards for inviting public input, and establish credible oversight systems. Document public input, and provide responses prior to adoption of final regulations.

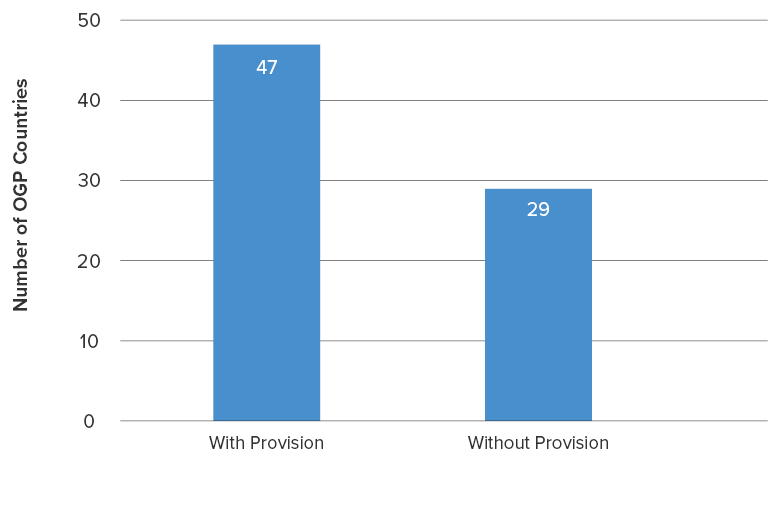

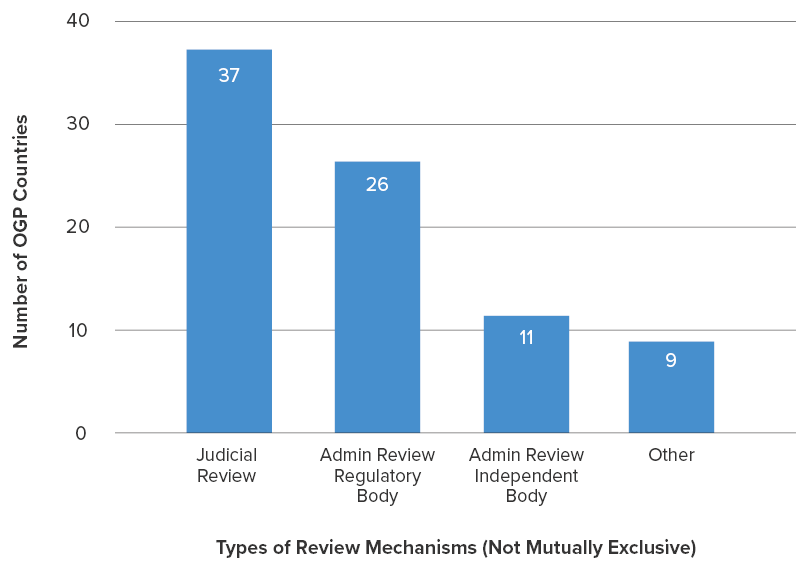

Challenging regulations

- State of play: Citizens in many OGP countries cannot challenge regulations on procedural grounds. In addition, only two OGP members have made commitments in this area to date.

- Recommendations: Adopt legislation that provides the legal basis to challenge regulations if not developed through open processes or if discriminatory. Publish information about the process and enable citizens to also challenge regulations on substantive grounds.

Introduction

The Case for Transparent and Participatory Rulemaking Processes

Transparency and accountability in government actions are increasingly recognized as central to economic development and political stability.[1] When citizens have effective access to the laws and regulations that govern their society and also have a role in shaping them, they are more likely to comply with those laws and regulations. Corruption is less common, and the quality of laws and regulations can significantly improve. In addition, citizen access to the government rulemaking process is central to the creation of a business environment in which investors make long-range plans and investments.[2]

Public participation in the rulemaking process can enhance transparency and strengthen both the quality and legitimacy of regulation – an important precursor for trust. Apart from being ends in themselves, these outcomes enhance fair and equitable implementation and enforcement of laws and regulations, which can improve equality of opportunity and level the playing field in all sectors. This is particularly important in key sectors like health care, energy, and transportation.[3] When citizens know and can influence the rules that govern their society, in addition to increased compliance with the laws by citizens and less corruption in the government,[4] public institutions tend to be more politically stable.[5] And if the new regulations are well-crafted and have clear benefits for society and/or business communities, transparent rulemaking achieves better compliance with and support for the scope and application of new laws.[6] Undeniably, good governance depends on stakeholder involvement.[7]

In the 20th century, many governments started moving in the direction of more open regulatory processes. Beyond consulting citizens during the development of regulations, several governments began recognizing the legal rights of citizens to challenge decisions and actions by regulatory officials. In the past few decades, the rise in e-government systems has provided governments more efficient ways to improve public participationGiving citizens opportunities to provide input into government decision-making leads to more effective governance, improved public service delivery, and more equitable outcomes. Technical specificatio... in rulemaking processes. In the early 2000s, the governments of countries such as Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States began posting the text of proposed regulations online for citizens to read and comment on. Regulators also realized the benefit of having open dialogues with stakeholders to discuss the areas of concern and receive their input. Mexico’s government passed a law in 2002 requiring federal ministries and agencies to make all draft regulations publicly available on their websites.

Measuring and Describing Regulatory Governance

The World Bank’s Global Indicators of Regulatory Governance (GIRG) project is an initiative of the World Bank’s Global Indicators Group that explores how governments interact with the public when shaping regulations. Building on the existing literature and with the aim of extending the analysis to developing countries, the project charts the extent to which – and how – citizens, civic organizations, and business associations around the world engage with governments on the content and scope of new regulations.

Central to GIRG is an effort to capture how rulemaking happens in practice in different jurisdictions, not just in terms of what is required by the letter of the law. Functionally, the project seeks to identify where governments offer citizens opportunities to voice their concerns about proposed and existing regulations meant to implement legislation. Plus, the project helps policy-makers identify how their government’s regulatory practices compare with those of others in the areas of transparent and inclusive rulemaking.

To gather the data, the GIRG project team developed a questionnaire with input from academicians, regulatory governance experts, and government practitioners. The team shared the questionnaire with more than 1,500 regulatory experts from across the world. After validation and verification, the resulting data cover 186 countries[8] (and the European Union), including all 78 OGP member countries. The data cover six areas of regulatory governance. The main chapters of this paper study four of these in-depth.

In terms of limitations, the GIRG project does not necessarily capture the quality of existing rulemaking processes and practices. For example, while the data set captures whether rulemakers engage stakeholders in consultation around proposed regulations, it does not reflect the quality of such discussions or the extent to which the comments lead to changes in proposed regulations. The data also do not reveal cronyism, nepotism, corruption, and bribery. Furthermore, the questionnaire asks about national-level regulatory practices at large, without focusing on any specific sector. Regulatory practices can differ from industry to industry and between national and regional levels of governments. More details about the methodology, as well as the full data set, are available online.

Structure of this Paper

The following short section “An Overview of Regulatory Governance Across OGP Action Plans” provides an overview of how OGP members are addressing regulatory governance through their action plans. The four main chapters of this paper, which focus on the topics covered by the GIRG project, continue afterward. At the end of the paper, the Annex provides short summaries of relevant reforms, grouped by chapter.

Feature: An Overview of Regulatory Governance Across OGP Action Plans

All OGP-participating governments are required to co-create a two-year action plan with citizens. These OGP action plans contain concrete commitments to advance transparency, participation, and public accountability in government. Many of these commitments fall into a category that OGP calls open policy-making, which refers to openness in government decision-making.[9] Although the rest of the paper focuses on the aspects of regulatory governance covered by GIRG, this section looks closely at this broader set of OGP commitments.

Open policy-making is a common focus of OGP commitments

Most OGP members have made at least one commitmentOGP commitments are promises for reform co-created by governments and civil society and submitted as part of an action plan. Commitments typically include a description of the problem, concrete action... related to open policy-making. Nearly 10 percent of all OGP commitments relate to open policy-making. Looking across regions, these commitments are most popular in Europe, although many OGP members in the Americas have also made relevant commitments.

OGP members are focusing on improving consultations

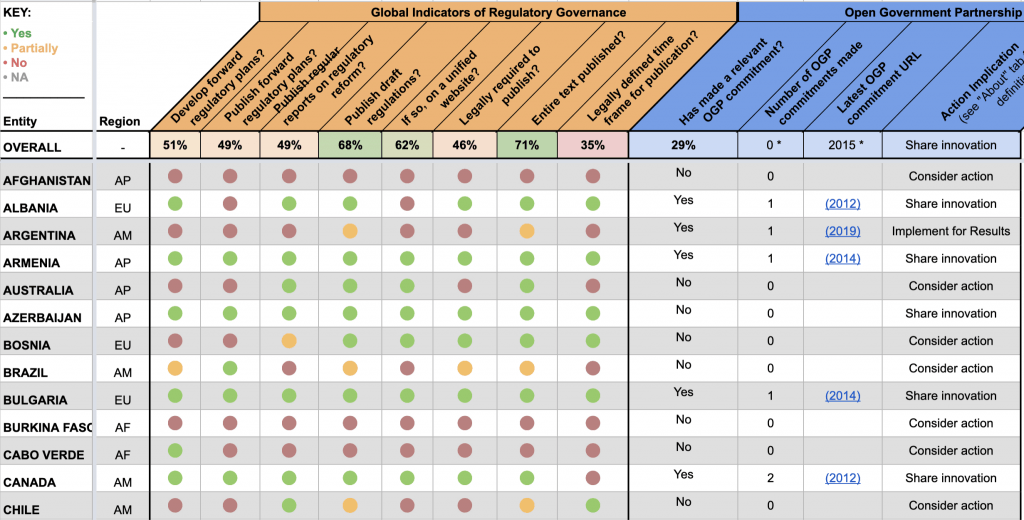

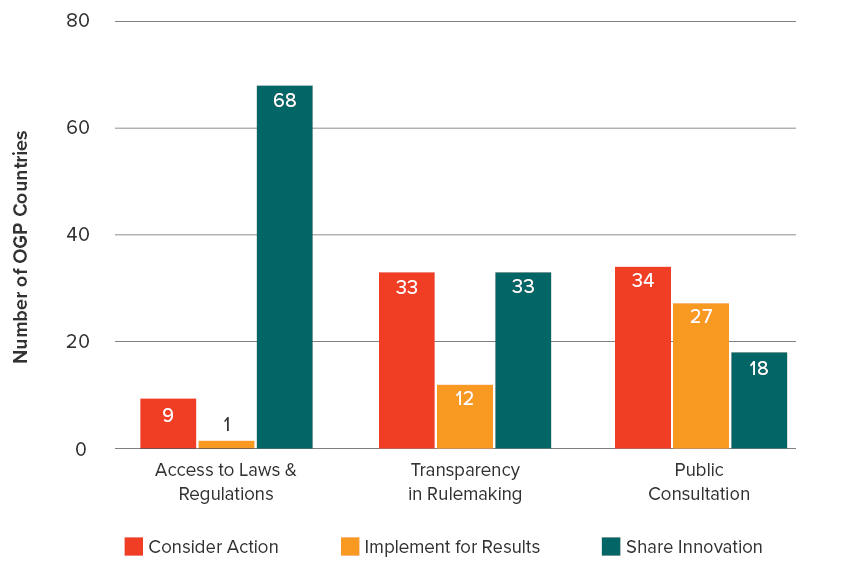

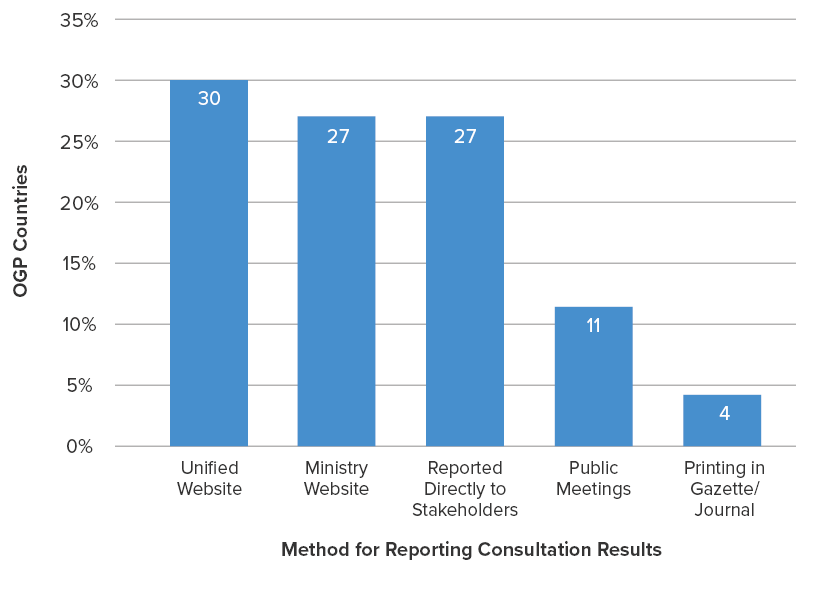

If grouped according to the four GIRG topics mentioned earlier, most OGP commitments fall into the category of “public consultation.” Figure I shows the distribution of commitments according to the GIRG categories. Specifically, 42 countries have made an OGP commitment aimed at improving consultations around regulations. Far fewer have made a commitment related to challenging regulations (only Latvia and Peru).

Figure I. OGP Commitments Related to Public Consultations Are Most Common

*Note that in this case the analysis includes OGP local members

Source: OGP commitment database, N=71

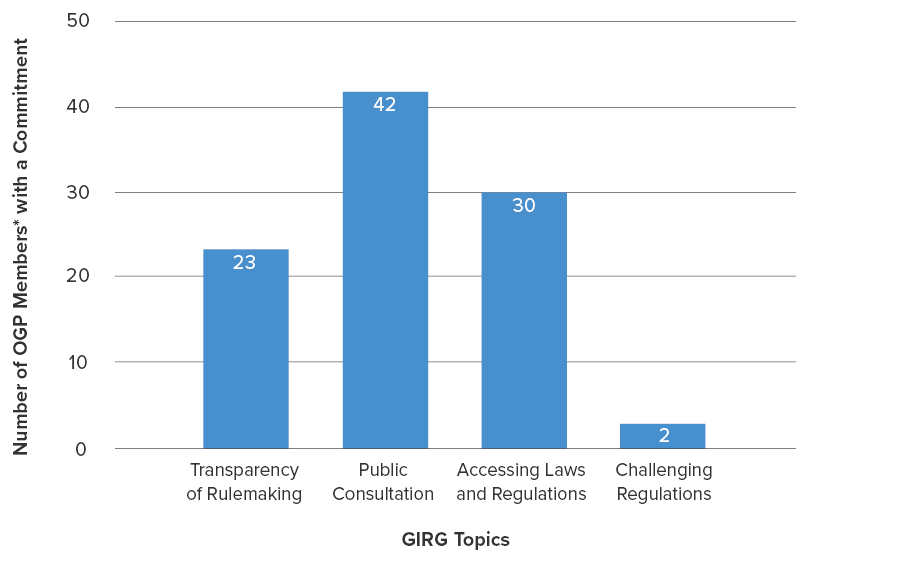

Although OGP commitments in general tend to focus on information disclosure, the majority of open policy-making commitments relate to civic participation. Figure II visualizes the distribution of OGP commitments on the three core OGP values: access to information, civic participation, and public accountabilityAccording to OGP’s Articles of Governance, public accountability occurs when ”rules, regulations, and mechanisms in place call upon government actors to justify their actions, act upon criticisms ... More. These commitments clearly focus more on engaging citizens than the typical OGP commitment. This may be a result of the technical difficulty involved in publishing laws and regulations, but it is nonetheless an encouraging sign of how OGP members are going beyond transparency-only reforms in this area. However, open policy-making commitments are less likely than OGP commitments in other areas to advance public accountability (i.e., create or improve concrete opportunities to hold officials answerable to their actions).

Figure II. Open Policy-Making Commitments in OGP Tend to Deal with Civic Participation

Open policy-making commitments in OGP go beyond GIRG’s largely regulatory framework

Many OGP commitments go beyond the areas covered by GIRG. In general, these commitments fall into the following categories:

- Issue-specific participatory processes: Nearly half of the commitments focus on involving the public in the creation of a single policy or plan or within a particular government agency. These commitments are not directly comparable to GIRG because they are not streamlined across government.

- Training and capacity-building: Some commitments focus on training government officials on how to make regulatory processes more participatory. Others train citizens on how to better participate in open regulatory processes.

- Legislative openness: GIRG covers the publication of laws, but many OGP commitments go further, including proposals to publish draft laws, data on voting, and international treaties. Some commitments also aim to better involve citizens in the process of drafting legislation.

- Publishing information about other parts of the lifespan of a regulation: This includes commitments that track the implementation status of regulations.

- Lobbying: Many OGP commitments aim to increase the transparency of those who directly influence the policy-making process. Many of these efforts cover both legislative and administrative interactions. This is also an active area of work in the OGP community.

- E-petitions: Many OGP commitments seek to create channels for citizens to directly petition their governments. For example, the Ravaalgatus.ee platform in Estonia allows citizens to create, digitally sign, and send proposals directly to the Parliament for consideration. (See “Lessons from Reformers: Estonia” at the end of Chapter 1).

Open policy-making commitments shine in Asia Pacific and the Americas

The Independent Reporting Mechanism (IRM)The Independent Reporting Mechanism (IRM) is OGP’s accountability arm and the main means of tracking progress in participating countries. The IRM provides independent, evidence-based, and objective ... assesses the quality and implementation of OGP action plans and collects data on commitments’ levels of ambitionAccording to OGP’s Articles of Governance, OGP commitments should “stretch government practice beyond its current baseline with respect to key areas of open government.” Ambition captures the po..., completionImplementers must follow through on their commitments for them to achieve impact. For each commitment, OGP’s Independent Reporting Mechanism (IRM) evaluates the degree to which the activities outlin... More, and early resultsEarly results refer to concrete changes in government practice related to transparency, citizen participation, and/or public accountability as a result of a commitment’s implementation. OGP’s Inde... More. According to these metrics, roughly half of open policy-making commitments are ambitious — or have the potential to change the status quo. Nearly two-thirds were substantially completed, and one in five led to significant improvements in government openness. These rates are roughly average compared to OGP commitments on other topics. Open policy-making commitments are especially strong in particular regions. For example, in Asia Pacific, they tend to be more ambitious than other commitments. Similarly, in the Americas, they are more likely to lead to significant changes in government practices than other commitments.

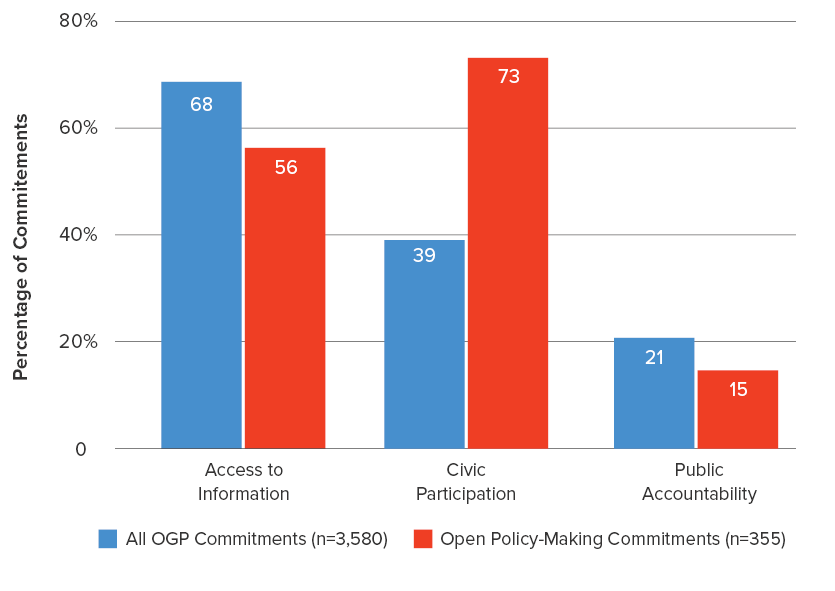

OGP countries are making laws and regulations available but without sufficient citizen involvement

Following the model of OGP’s Global Report, OGP members can be categorized based on the strength of their third-party score (GIRG in this case) and whether they are using the OGP platform to improve. The following table, Table III, shows that OGP members perform best in publishing laws and regulations (see Chapter 1, “Accessing Laws and Regulations” for more details). Performance is weaker in the transparency of rulemaking (i.e., public notice of upcoming changes). OGP members fare worst in consulting citizens regularly on draft rules, but many have made OGP commitments to improve practice in this area. The reason for such poor performance is likely the lack of legal obligation that requires officials to follow stipulated public notice-and-comment requirements, provides minimum standards of compliance, and establishes oversight systems to monitor compliance.

Figure III. OGP Countries Perform Best in Publishing Laws and Regulations

Source: Global Indicators of Regulatory Governance and OGP databases, N=78

Key

- Share Innovation: These countries have the maximum GIRG score in the respective policy area. As leaders, they may consider playing a peer-support role by sharing their experiences and innovations with others in OGP, if they are not already doing so.

- Implement for Results: These countries have not attained the maximum GIRG score in the respective policy area but have made OGP commitments to improve their performance. Having demonstrated political commitment through OGP, the next step for these countries is to ensure that implemented commitments have maximal impact.

- Consider Action: These countries have not attained the maximum GIRG score in the respective policy area and also have not leveraged their OGP action plans to address the issue. They may consider reforms in the respective policy area, either within or outside of the OGP framework.

Strong OGP co-creation is not associated with strong performance on GIRG

A key element of OGP is co-creation of action plans by government and civil society. The IRM assesses the level of public influence during the process of developing each action planAction plans are at the core of a government’s participation in OGP. They are the product of a co-creation process in which government and civil society jointly develop commitments to open governmen... (e.g., whether citizens were consulted and received a response to their input). An analysis of this IRM data and the GIRG public consultation scores reveals that there is no statistical relationship between the two indicators. In other words, the strength of OGP co-creation is not indicative of strong consultation practices across government. This is a significant finding that points to a clear recommendation: OGP members can do more to mainstream open regulatory processes across government.

Sometimes, the OGP process is more participatory, contrasting sharply with general government practices. For example, the government of Argentina developed its 2017–2019 OGP action plan in close collaboration with citizens through in-person workshops, online crowdsourcing of ideas, and carefully documented consultations. Nonetheless, according to GIRG, this type of participatory process is not yet common across the Argentinean government. In other cases, OGP countries have participatory regulatory processes that are mandated by law but that do not translate into co-creation of OGP action plans. In both examples, governments should share innovative approaches across the administration to mainstream open regulatory processes.

1. Accessing Laws and Regulations

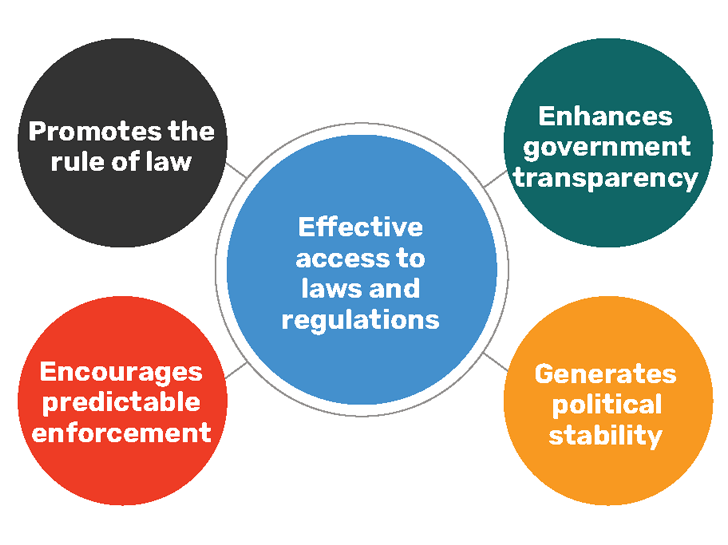

The World Bank’s Global Indicators of Regulatory Governance (GIRG) measure the accessibility of laws and regulations. Open and effective access to laws is pivotal to understanding and applying the rule of law. It is considered a crucial component of any modern legal system, as it encourages predictable enforcement and transparency, promotes the rule of law, and generates political stability (see Figure 1.1). In a scenario where citizens know and understand the rules that govern their society, they are more likely to comply with those rules. If people have efficient, effective, and free access to the country’s laws and regulations, they are in a better position to exercise their legal rights, plan and predict their actions, and efficiently resolve any arising problems and disputes. This is why improving legislative openness is an important area of work for OGP as well.

Figure 1.1. Access to Laws and Regulations Is a Core Pillar of Good Governance

Clear and transparent legal and regulatory structures also enable local businesses to thrive without fear of selective, arbitrary, or capricious actions and decisions by regulatory officials. Consider a small enterprise trying to comply with formalities outlined in local regulations, such as fee schedules, corporate regulations, and taxPlacing transparency, accountability, and participation at the center of tax policy can ensure that burdens are distributed equitably across society. Technical specifications: Commitments related to c... requirements. When countries facilitate effective access to laws and regulations, compliance is easy and straightforward, saving time and money for both businesses and authorities. In turn, when tax regulations are ambiguous and regulatory officials use an opaque process to interpret, apply, and enforce them, legal and regulatory provisions are likely to be subject to multiple interpretations by officials in the same agency. In such an environment, companies must spend extra time attempting to comprehend the requirements and often must seek expensive legal assistance to be able to navigate and accurately interpret local tax compliance regulations. For entrepreneurs, the lack of legal certainty is overly burdensome, costly, and unproductive, as well as a sign of a weak pro-business environment and is one of the main reasons for disincentivizing private investment.

In the absence of regulatory transparency, rent seeking and shadow deal making are likely to become the norm and accepted culture of regulatory governance, or the modus operandi. For instance, when laws are not easily accessible, resolution of court disputes largely depends on subjective legal interpretations by judges, which may be greatly at odds with how an agency is interpreting, applying, and enforcing its own laws and regulations. Furthermore, research demonstrates that obstacles and constraints to accessing applicable laws in some economies deter legitimate foreign investors – who want to comply with laws honestly and transparently – and also weakens trade policies.[10] Foreign investment tends to be higher in economies where legal frameworks ensure transparency, predictability, and adherence to the rule of law.[11]

The following maturity model summarizes the key actions that OGP members should implement to ensure free and easy access to their current laws and regulations.

Maturity Model for Future Actions: Effective Access to Official and Full Versions of Laws and Regulations |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Note: These actionable items are discussed in greater detail further in the chapter.

Good to Know: How the GIRG project assesses publication of laws and regulations The GIRG data assesses transparency and ease of access to laws and regulations in all 78 OGP member states by asking the following questions:

The answers to these questions provide a picture of the overall availability of laws and regulations in each country. It is important to note that the GIRG data do not delve into more methodologically difficult questions of data quality, such as whether the information is useful, usable, or used. For example, countries may publish legal and regulatory information that is incomplete, inconsistently updated, or made up of unofficial versions that contain errors. The information may also not be searchable or user-friendly. In effect, legal and regulatory information may be available yet unreliable in ways that the data cannot fully capture. According to experts,[12] these data quality issues are a particular challenge in many African countries, as noted also by organizations such as the African Legal Information Institute. |

Most OGP members provide full and effective access to an official collection of laws and regulations

Reassuringly, out of 78 OGP countries, 68 maintain unified websites where laws are made publicly accessible in a single place (see Table 1.1). Additionally, 23 countries have made commitments through the OGP platform to improve citizen access to current laws and regulations, such as Romania:

- The Romanian government provided free and comprehensive access to legislation for all its constituencies. Previously, access to consolidated national legislation was only available for a fee, and the official gazette was only available free of cost for a ten-day window. With this commitment, citizens now have unlimited, free access to these resources via an online government portal, marking a major improvement to Romanian citizens’ access to information. Additionally, during the commitment’s implementation, in response to civil society concerns on the role of intermediaries in the process, a new law was drafted (195/2016) to ensure permanent and free access to the official gazette. This commitment is also aligned with the EU and national-level standards, which designate free access to legislation as essential to legal compliance.

New Zealand Parliament. Photo by: asanojunki0110 Lessons from Reformers: New Zealand commits to publishing secondary legislation online Although New Zealanders prior to 2016 could access their country’s legislation for free on legislation.govt.nz, the same was not true for secondary legislation (mostly rules and regulations), which were often unavailable in machine-readable formats or not available at all. As a result, as part of its 2016–2018 OGP action plan, the government committed to centralizing all official primary and secondary laws online – including those drafted by Crown entities, statutory bodies, and other nongovernmental bodies. Implementation has required a multitiered process. An initial step involved conducting a legal review to identify acts that constitute secondary legislation as opposed to mere administrative provisions. The Parliamentary Counsel Office (PCO) in charge also carried out external research to better understand how people access and use secondary legislation. These insights will inform later stages of the project. As an intermediate next step, in its follow-up 2018–2020 OGP action plan, the PCO committed to listing all secondary legislation on the main legislation website with hyperlinks to the location of the text. Beyond the importance of providing easy access to all legislation online, New Zealand’s step-by-step approach is also a model for other countries looking to integrate long-term ambitious reforms into the two-year OGP action plan cycle. |

Table 1.1 Most OGP Countries Provide Access to Laws and Regulations

ACCESSING LAWS AND REGULATIONS | ||

Best Performers | Weak Performers | |

Full access (score: 1) | Some to no access (score: 0–0.5) | |

OGP commitment | Albania, Argentina, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Dominican Republic, Estonia, Finland, France, Georgia, Honduras, Italy, Mexico, Moldova, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Paraguay, Portugal, Romania, Slovak Republic, Serbia, Spain, United Kingdom, United States | Liberia |

No OGP commitment | Afghanistan, Australia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Brazil, Bulgaria, Burkina Faso, Cabo Verde, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, El Salvador, Germany, Greece, Indonesia, Ireland, Israel, Jamaica, Jordan, Kenya, Korea (Republic of), Kyrgyz Republic, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Mongolia, Montenegro, Morocco, North Macedonia, Norway, Pakistan, Panama, Papua New Guinea, Peru, Philippines, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Sweden, Tunisia, Ukraine, Uruguay | Côte d’Ivoire, Ecuador, Ghana, Guatemala, Malawi, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Seychelles |

However, a handful of OGP countries need to do more to ensure basic citizen access to current laws. Ten OGP countries provide partial or no access to adopted laws and regulations. Eight of the countries are in Africa while two are in the Americas. Of the ten countries, only Liberia has made a commitment to address this issue. Specifically, in its 2017 OGP action plan, recognizing that the public is largely unaware of the status of critical bills, the government committed to 1) creating a database to track laws and bills in the legislature, 2) providing regular reports with this information, and 3) hosting roundtables to enable discussion. Other countries could consider similar efforts to improve the accessibility of laws and regulations.

Parliament Building in Cape Town. Photo by dpreezq Lessons from Reformers: South Africa’s push for open access to legislation South Africa particularly benefited from providing open access to legislation and set an example that other countries can follow. When a government provides open access to laws, informed citizens become better equipped to participate in decisions demanded by a democratic system. During the apartheid era in South Africa, access to information on social and economic affairs was purposefully suppressed. Laws were published in the government gazette known as Staatskoerant with very limited access. Opposition groups severely criticized the general secrecy of government, which enabled the gross violation of human rightsAn essential part of open government includes protecting the sacred freedoms and rights of all citizens, including the most vulnerable groups, and holding those who violate human rights accountable. T.... After the election in 1994, the right to access information was embedded in the Constitution, and in 2001, the Promotion of Access to Information Act came into force. The act established the constitutional right of access to any information – held by the government or others – necessary for the exercise or protection of rights. Today, the South African government gazette makes legal texts available to the public in printed form as well as electronically and has played a key role in supporting democratic stability and promoting the rule of law in the country. Free access to information was crucial for educating political activists as well as civil society and bringing about positive political change in the country.[13] Now all South African legislation is publicly available through the Parliament’s website. Many thanks to former OGP Steering CommitteeThe Steering Committee is OGP’s executive decision-making body. Its role is to develop, promote and safeguard OGP’s values, principles and interests; establish OGP’s core ideas, policies, and ru... co-chair Mukelani Dimba for his contributions to this story. |

Official gazettes are an important mechanism for publishing laws and regulations

Access to laws and regulations through an official gazette or similar publication is an important way to publicize legal texts. A gazette is a viable mechanism to keep citizens abreast of the current laws, especially in countries with low levels of Internet penetration. Forty-nine OGP countries make the laws available through both unified websites (government-run) and official printed gazettes (see Figure 1.2). Eight OGP countries – Côte d’Ivoire, Ecuador, Ghana, Malawi, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Serbia, and Seychelles – only use official gazettes to disseminate laws and regulations to the general public. In the case of Nigeria, laws passed by the National Assembly are available in the federal gazette (Federal Republic of Nigeria Official Gazette), while state laws are available in the respective state gazettes. In most African countries (and in many others), laws are not enforceable until they are published in the gazette. Thus, it represents a critical legal role in addition to dissemination. Additional country-specific findings follow:

- Many countries publish gazettes online. In Moldova, the official gazette[14] is usually published twice a week (hard copy only). It contains all the amendments to the laws and regulations in effect. In many countries, especially high-income ones, gazettes can be accessed electronically and free of charge. Some examples of such countries include Australia, Germany, Serbia, Sri Lanka, and Tunisia.

- In Greece, the National Printing House is responsible for issuing the Government’s Gazette. The gazette comprises all current laws and other regulatory acts, such as presidential decrees and ministerial decisions. It is available free of charge, but an e-copy has to be ordered by email.

However, gazettes can be futile if they do not include up-to-date information or if citizens are unaware of their existence. In Afghanistan, the official gazette published by the Ministry of JusticeTo address barriers that prevent citizens from having their justice needs met, OGP participating governments are working to expand transparency, accountability, and inclusion into all systems of justi... can only be bought in stores (although the government also maintains a website that enables free access to laws). Storage of paper copies of gazettes can also be problematic. For example, in Seychelles, it is difficult to obtain historical copies of gazettes (i.e., more than five years old). The local government also finds the effort to consolidate all the laws and regulations to be costly and labor-intensive. Therefore, major legal compilations and revisions take place only once about every ten years. In many African countries, the updates are even less frequent.

Figure 1.2 Most OGP Countries Make Primary Laws Available in a Single Place

Source: Global Indicators of Regulatory Governance database, N=78.

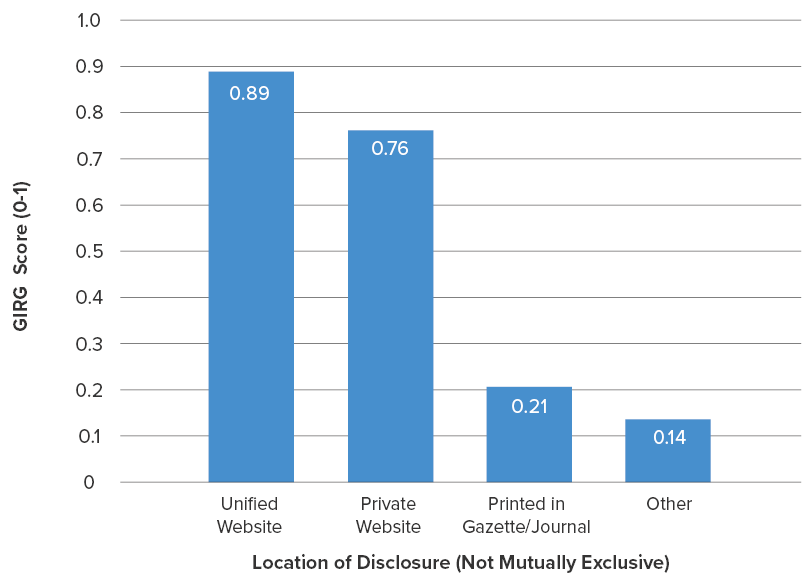

Nearly 90 percent of OGP countries use a unified website to publish laws and regulations

Maintaining freely available, searchable, and up-to-date websites containing complete and official versions of all existing legislation is a best practice that all OGP countries should strive for. Studies suggest that initial costs of publication may contribute to preventing subsequent additional and sometimes burdensome costs derived from litigation as a result of ignorance of the law. In general, OGP countries make both primary and secondary laws available to constituencies in a single place, most often through a unified government-run website (see Figure 1.2). Examples of strong performers follow:

- Australia is one of the champions of transparent and effective information sharing. The Australian government has developed several initiatives to have laws freely available online to the general public. The Federal Register of Legislation is a comprehensive government website for the public to access Australian laws and related legislation. The website provides accessibility to full texts of laws as well as electronic copies of the government’s gazette all the way back to 1901. It includes acts of Parliament, act compilations, regulations, administrative arrangement orders, legislative instruments, explanatory statements, and other instruments. The online government website was implemented in accordance with the Legislation Act 2003, which provided a comprehensive regime for the management and dissemination of laws and mandated public online access to authorized versions of legal texts, associated documents, and information.

- Kenya is a noteworthy example of enhancing electronic dissemination of primary and secondary legislation. The Kenya Law, a 2001 state-funded initiative, implemented an online system for legal reporting aimed at 1) revising, consolidating, and publishing Kenyan laws; 2) monitoring and reporting the development of Kenya’s jurisprudence; and 3) providing universal access to the county’s legal information. The Kenya Law website features a comprehensive database of laws, which is easily accessible and searchable. It also provides a substantive collection of subnational laws and international treaties. In addition, through the online platform, users can access the official country gazette as well as historical legal documents. More recently, the government has begun using an open, nonproprietary format to consolidate and publish legislative documents and is among only a handful of African governments that consolidates and publishes its own legislation.

- South Korea uses a comprehensive online platform to provide access to laws. Over a decade ago, the Ministry of Government Legislation of South Korea implemented the National Law Information Center, which is essentially an online platform that provides integrated and free access to Korean legislation, including statutes, administrative regulation, and local governments’ ordinances, as well as regulations and statutory interpretation cases. The legal database is organized by legislative bodies and by key regulatory areas. Most recent amendments are featured on the homepage and are searchable by both date and subject. The center also offers a legal information service that summarizes the content of specific laws and regulations in an easy-to-understand story-telling format so that citizens can better interpret relevant legal provisions.

- The European Union’s online platform, EUR-Lex, provides free legal information at both supranational and national levels. Treaties, directives, regulations, decisions, and consolidated legislation are all available electronically. Moreover, the website contains European Union case law, international agreements, summaries of legislation, and other public documents. It also provides direct access to the official journal. The website is administered by the European Union e-Law Working Party, which is composed of representatives of the 28 member states, the EU Publication Office, the EU Commission, and the General Secretariat of the EU Council.

The private sector plays an important role in providing access to laws and regulations

Private sector legal databases provide access to regulations in some countries, but they are not a magic bullet. Free access to a reliably updated, official, and comprehensive collection of laws and regulations is a basic public good that governments – not the private sector – are responsible for providing. Problems of quality, access, and sustainability arise when governments outsource this function (or have no role in the system). For example, privately run platforms may contain errors (due to lack of official reviews) and may not be systematically updated. In addition, introducing fees deprives the most vulnerable from accessing the laws they need to protect their rights. A provider can also go out of business or otherwise interrupt access. Beyond these issues, outsourcing to private companies often prevents the transfer of knowledge, skills, and capacity that government officials need to perform these functions.

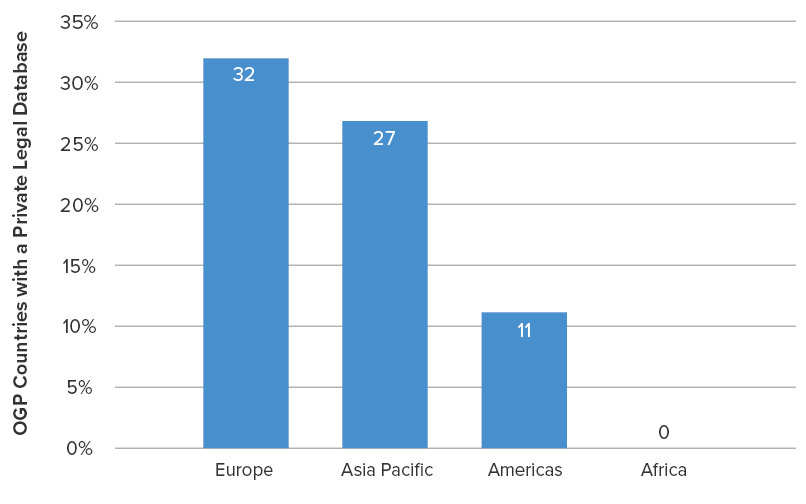

Despite these drawbacks, fourteen OGP countries – Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Germany, Denmark, Israel, Italy, Sri Lanka, Lithuania, Norway, Panama, Philippines, Papua New Guinea, Serbia, and Ukraine – have private sector websites that compile large legal databases of both primary and secondary laws. Among the 78 sampled OGP countries, most private legal databases are in Europe, followed by Asia Pacific (see Figure 1.3). This pattern could be demand-driven and subject to the availability of paying clients to maintain operational business models.

Figure 1.3. Private Sector Legal Databases Are Most Widespread in Europe

Source: Global Indicators of Regulatory Governance database, N=78.

Worldwide, a number of private companies specialize in offering prepaid online legal databases. This is a thriving industry that caters to the needs of attorneys, judges, law students, accountants, and entrepreneurs. Private platforms provide efficient and easy access to search tools that allow rapid identification of specific legal materials. Privately operated legal databases enable users to effectively retrieve all the relevant information pertinent to a specific query, including legislation, case law, and secondary materials, such as scholarly works.

One of the leading global data providers in the industry is the LexisNexis Group. LexisNexis is a US-based corporation that provides services for 175 jurisdictions, offering one of the largest electronic databases for legal information and access to five billion searchable documents from more than 40,000 legal, news, and business sources. The company also offers business information solutions to professionals in a variety of areas, including legal, corporate, government, law enforcement, tax, accounting, and academic, as well as risk and compliance assessments. However, as discussed earlier, privately provided sources of laws and regulations should be a complement to – not a replacement of – the official source of legislative texts. In many cases, private services are stepping in because governments are not fulfilling an important governance function, which – perhaps counterintuitively – can hinder access for a broad swath of the population, impact the reliability of information, and introduce conflicts of interestA key part of anti-corruption involves preventing or revealing conflicts of interest — when a public official is in a position to use public office for personal or private gain. Technical specificat....

OGP countries may benefit from collaboration with private platforms. In many jurisdictions, proliferation of prepaid legal online platforms is a response to inefficiency, inaccuracy, or incompleteness of government-run websites. However, OGP countries could benefit from active collaboration with private data aggregation platforms to improve access to information for their citizens. For example, private platforms can help to channel information from different government websites into a single-search source engine. They can also offer tools to help users better understand legislation. However, in these cases, it is important for the government to retain control of key information around its laws and regulations to ensure free and comprehensive access.[15] See “Good to Know: Nongovernmental actors play a key role in open access to laws” for a discussion of the important role that civil society plays in this area. Also, see “Lessons from Reformers: Albania” at the end of this chapter for an example of civil society spearheading the publication of government legislation.

Good to Know: Nongovernmental actors play a key role in open access to laws In some countries, open access to laws is provided by academia or independent organizations. These types of initiatives, led mostly by universities and legal advocacy groups, are known as the “Legal Information Institutes” or “the Free Access to Law Movement.” The concept, which was first created at the Cornell University Law School in 1992, is that legal information should be freely accessible and not subject to monopolistic practices. In these cases, legal information is published from different sources in a collaborative data sharing effort from different networks. For example, the Asian Legal Information Institute provides over 300 databases from 28 countries in Asia. Similarly, the Commonwealth Legal Information Institute serves as a repositoryAccess to relevant information is essential for enabling participation and ensuring accountability throughout the OGP process. An OGP repository is an online centralized website, webpage, platform or ... of legal information, covering over 1,400 databases from 60 Commonwealth and common law jurisdictions. Other examples include the African Legal Information Institute, a project of the Democratic Governance and Rights Unit at the University of Cape Town and the Pacific Islands Legal Information Institute, an initiative of the University of the South Pacific School of Law. |

Keeping legal databases up to date is a challenge for many OGP countries

The ways in which OGP countries update their legal databases show considerable variation (see Table 1.2). The most common practice is to publish an updated law within two to seven days after its enactment. This is the case in over 50 percent of OGP countries. Bulgaria makes legal updates on the same day that the State Gazette is printed and distributed. In Estonia, updates take place within seven days upon signature or proclamation, while systems in the UK ensured that the legislation related to Brexit was uploaded, indexed, and accessible the same day it was enacted.

- Some countries, such as Peru, have implemented automated systems allowing for immediate publication of legal amendments. The Peruvian Ministry of Justice and Human Rights makes same-day updates to all the amended laws and regulations through the Peruvian Legal Information System (SPIJ). The updates are also reflected in the official gazette “El Peruano.”

- In other OGP countries, it takes one to three weeks to update amendments in legal publication systems. This is the case of Mongolia, where new laws and regulations are published in the State Bulletin within fourteen days after their adoption. In eight OGP countries – Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Guatemala, Liberia, Papua New Guinea, Senegal, and Sierra Leone – lack of regular updates of legal databases is particularly problematic.

Table 1.2: Frequency with which Countries Update Legal Databases

2 weeks or less | within 1 month | more than 6 months |

Argentina, Armenia, Australia, Azerbaijan, Bulgaria, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Croatia, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Georgia, Germany, Greece, Israel, Luxembourg, North Macedonia, Malta, Mexico, Morocco, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway , Pakistan, Paraguay, Peru, Romania, Sweden, Ukraine, United Kingdom, Uruguay | Afghanistan, Czech Republic, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Jordan, Kenya, Montenegro, South Africa | Bosnia and Herzegovina, Burkina Faso, Cabo Verde, Côte d’Ivoire, Ecuador, Ghana, Guatemala, Honduras, Jamaica, Liberia, Malawi, Papua New Guinea, Senegal, Sierra Leone |

Source: Global Indicators of Regulatory Governance database.

Areas for innovation: Moving toward comprehensive and user-friendly disclosure

Providing effective access to all laws and regulations from different levels of government is an area for improvement across OGP countries. Many countries have unified websites that consolidate only national-level regulations, while there is no platform where regional and local regulations are accessible in a single place. Albania is an exception:

- Albania published local government acts on a single portal. As part of Albania’s 2016 OGP action plan, all 61 Albanian municipalities made their municipal decisions available online on vendime.al. See “Lessons from Reformers: Albania” at the end of this chapter for more details.

The issue of compiling national and regional regulations is particularly challenging in some EU countries where multilayered regulations are not consolidated and hence might not be implemented coherently across different regulatory strata.[16] One of the easier ways forward could be to first ensure that all the local regulations are made publicly available through regional and municipal electronic systems hosted and maintained by appropriate regulatory authorities. Then, regional/municipal data sets can be combined with the national-level ones.

Legal texts should also be easy to understand and apply to day-to-day operations. Thus, regulators have to create the necessary conditions for citizens not only to access laws but also to fully comprehend them. A few countries have already made initial progress in this area:

- Chile looks to reduce language barriers in accessing legal texts. To ensure citizens’ understanding of the laws, the Library of Congress in Chile offers multiple programs aimed at facilitating interpretation of legal texts as well as generating general awareness of new regulations. For instance, one such program targets indigenous populations by translating and distributing legal guidelines in four selected indigenous languages. Multiple workshops are organized by the Library of Congress to explain how regulations impact the rights and lifestyles of different communities.

- The US focuses on user-friendly regulations. As part of its 2015 OGP action plan, the US government piloted the use of a new “eRegulations” application for citizens to more easily read and comment on regulations. Three agencies began using the application to publish their regulations. The tool provides in-line definitions and interpretations, allows comparison of different versions of regulations, and improves viewing regulations on mobile devices.

Conclusion

Most OGP countries already provide free access to existing laws and regulations, both primary and secondary ones, through unified websites. In addition, more than half of OGP countries complement unified and ministry-specific websites with printed copies of all legislation. Given the high demand for easy and reliable access to massive legal databases, in many countries, the private sector complements governments’ electronic records by offering customized and comprehensive legal search tools.

However, a key area for improvement is ensuring that regulatory data sets are systematically complete and up to date and include certified official versions. It is imperative for all the legal changes to be reflected as soon as possible across all public domains, ensuring access to reliable information. In addition, OGP countries can innovate further, such as by disclosing both national and subnational legislation and by improving the readability and comprehension of laws and regulations among a wider segment of the population.

Albanian activists review information available through the digitalization and online publication of decisions of the Shijak Municipal Council. Photo by: https://www.vendime.al/fotolajm/ Lessons from Reformers: Albania publishes local government legislation online Emiriola Velia had a difficult time getting the answers she needed. As the representative of a regional youthRecognizing that investing in youth means investing in a better future, OGP participating governments are creating meaningful opportunities for youth to participate in government processes. Technical ... More council in Kukës in northeastern Albania, Velia relied on understanding the actions taken by her local government to organize and engage effectively in the political process. However, municipal council decisions were not easily accessible. She had to request the information directly from the government, which meant it often took three to four weeks before she received the information she needed. Today, this process looks a lot different. A civil-society driven reform has led to all 61 of Albania’s municipalities publishing municipal council decisions online on a central platform. Background Velia’s experience was not an isolated example. Albania’s system for publishing government legislation was fragmented and inefficient. Though legally required, few local governments provided access to legislation – including municipal council decisions. Many even lacked official websites through which to share information with citizens. In 2016, only 12 of the 61 municipalities published local legislation. This lack of information was a serious problem, especially given new decentralization reforms that endowed local governments with a greater range of responsibilities. The Center for Public Information Issues (INFOCIP), an Albanian NGO that promotes transparency and the rule of law, had been advocating for the online publication of local decisions since 2009. INFOCIP maintained a platform – vendime.al – that included information from an increasing number of municipalities. The organization partnered with the Ministry of State for Local Issues and pushed for further publication of decisions in the framework of the decentralization reforms. Albanian municipalities publish legislation online on a single platform for the first time At the urging of INFOCIP, the Albanian government committed to publishing central and local government legislation online on vendime.al as part of its 2016–2018 OGP action plan. Several donors (including the National Endowment for Democracy, the US embassy, and UNDP’s STAR project) supported municipal efforts to disclose legislation. Many municipalities received financial support from INFOCIP itself. Implementation was swift. According to INFOCIP’s monitoring reports, although only 20 percent of municipalities disclosed local legislation in 2016, this rate increased to 67% by 2017. Most important, by 2018, all 61 Albanian municipalities published local legislation on vendime.al. At this point, the platform hosted more than 20,000 municipal council decisions. Data usage grew alongside the increase in information available. Users viewed 1.5 million pages on the site in 2018, compared to about 240,000 when the site first launched in 2013. Altogether, more than 140,000 unique users (equivalent to 5 percent of Albania’s population) visited the site and recorded almost ten million hits. Lessons learned from the Albanian experience

Access to government legislation is an essential component of good governance. When citizens are better informed, they are empowered to use that information to shape policies, services, and budgets. In Albania, Emiriola Velia can now access all of her local government’s acts online. She no longer has to file information requests to get the information she needs. This saves her time and helps her regional youth council monitor their municipality’s decisions in real time. As more countries like Albania undertake similar reforms to publish legislation, ensuring that results permeate across all levels of government will be critical. This story was made possible through an interview with Gerti Shella (Executive Director, INFOCIP). |

2. Transparency of Rulemaking

Providing public notice of proposed regulatory changes is part of ensuring predictability in the regulatory environment, an aspect that has long been key for firms seeking to make long-range plans and investments. Foreign investors seek insight into the rulemaking plans of the economies in which they invest, both to inform their operations there and to avoid situations where domestic actors receive preferential treatment. Where citizens know the rules that govern their society and have a role in shaping them, they are more likely to comply with those rules. Corruption is lower, and the quality of regulation is higher.

Transparency of rulemaking includes multiple components. This comparative study assesses one of the key aspects of regulatory transparency – whether governments develop forward regulatory plans, that is, a public list of anticipated regulatory changes or proposals intended to be adopted or implemented within a specific time frame. In many countries, public notices include a wide range of information on proposed regulation. In Estonia, for example, the government provides a short summary of the proposed regulation and explains why the regulation is needed, what it is intended to change, and when it is expected to enter into force. In Lithuania, advance public notices are similar to those in Estonia but also include analyses of expected positive and negative impacts of the proposed regulatory changes.

The following maturity model summarizes the main pillars of good practices in the area of regulatory transparency that all OGP members should have in place. The rest of this chapter discusses each of these actions in greater detail and provides examples of reforms that countries are already implementing.

Maturity Model for Future Actions: Transparency of Rulemaking |

|

|

|

|

|

Note: These actionable items are discussed in greater detail further in the chapter.

Several OGP members have made commitments to further transparency in rulemaking processes

Ten countries have made commitments in this area across multiple OGP action plans. Altogether, 21 OGP members (27 percent) have made commitments to publishing forward regulatory plans (see Table 2.1), of which 12 are European countries, including the following:

- Moldova made draft policies publicly available. Moldova’s first commitment aimed to post information on draft policies and legislations, while the second looked to improve and further develop an online participation platform.

- Greece improved an electronic platform for public engagement. As part of its OGP commitment to increasing regulatory transparency, Greece improved an e-platform for publication and annotation of new laws and regulations prior to their submission to the Parliament. The website allows citizens, firms, and civil society organizations to log comments, annotations, proposals, and changes to legal texts.

- Kyrgyz Republic is improving transparency and public engagement by learning from past mistakes. In 2009, the Kyrgyz Republic put forward a legal requirement for public discussion of draft normative and legal acts. However, implementation of the legal provisions has been ineffective for several reasons, such as a lack of forward planning, the absence of a notification system to inform citizens of available drafts, and the lack of a mechanism to respond to comments. Through its OGP action plan, the country committed to remedying these shortcomings by 1) legally amending the rulemaking process to clarify how citizens will be involved and 2) developing a unified portal for draft normative acts, which will enable citizens to provide input and receive feedback.

- Latvia will enable citizens to access legal drafts and participate online in one place. Previously, citizens had to check individual ministry websites to track the development of new draft policies and legal acts. In 2015, the government committed to building a single portal for developing policies that would enable both governmental and nongovernmental actors to track changes in draft documents over time. This long-term project would allow citizens to follow draft legislation through multiple stages of revisions and provide ongoing feedback, up to adoption and enforcement. For an example of a similar reform, see “Lessons from Reformers: Estonia moves from online consultation to co-creation” at the end of this chapter.

Table 2.1 Several OGP Countries Perform Well in Transparent Rulemaking Processes

TRANSPARENCY OF RULEMAKING | |||

Best Performers | Intermediate Performers | Weak Performers | |

Forward regulatory plans are published throughout government and are publicly available (score: 1) | Some ministries/regulatory agencies publish forward regulatory plans (score: 0.5 – 0.75) | Do not publish forward regulatory plans (score: 0) | |

OGP commitment | Armenia, Bulgaria, Canada, Estonia, Finland, Croatia, Ireland, Moldova, the Netherlands, the United States | Albania, Colombia, Georgia, Kyrgyz Republic, North Macedonia, New Zealand | Greece, Guatemala, Israel, Latvia, Mongolia, Paraguay |

No OGP commitment | Azerbaijan, Costa Rica, Czech Republic, Germany, Denmark, France, Indonesia, Italy, Korea (Republic of), Lithuania, Luxembourg, Morocco, Mexico, Malta, Montenegro, Norway, the Philippines, Serbia, Slovak Republic, Spain, Sweden, South Africa, the United Kingdom | Brazil, Côte d’Ivoire, Cabo Verde, Jamaica, Nigeria, Senegal, Ukraine | Afghanistan, Argentina, Australia, Burkina Faso, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Chile, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Ghana, Honduras, Jordan, Kenya, Liberia, Sri Lanka, Malawi, Pakistan, Panama, Peru, Papua New Guinea, Portugal, Romania, Sierra Leone, El Salvador, Seychelles, Tunisia, Uruguay |

Source: GIRG and OGP databases.

Most OGP countries still do not publish forward regulatory plans

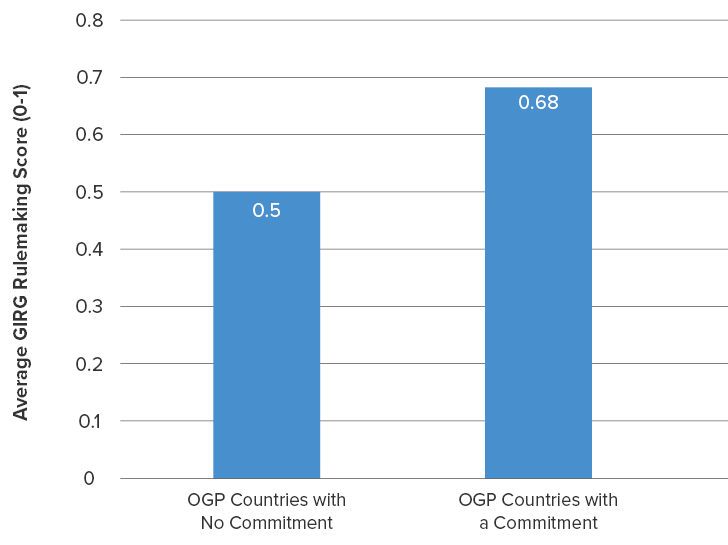

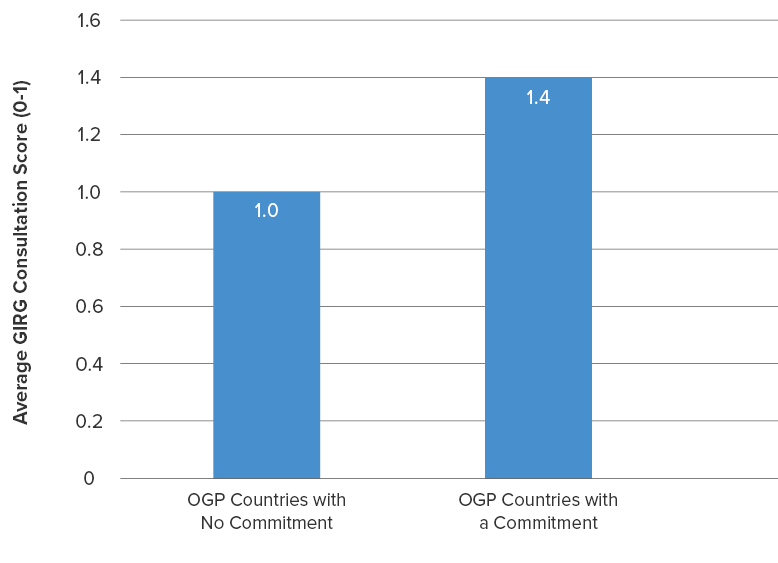

A forward regulatory plan describes regulatory changes that a government institution intends to propose. In general, fewer than half of OGP countries (42 percent) consistently publish forward regulatory plans across government. This may be due to the lack of legal provisions requiring this disclosure. However, countries with an OGP commitment in the area of transparent rulemaking also tend to have a higher GIRG score, which could suggest that countries are leveraging their OGP commitments effectively to make rulemaking processes more accessible and inclusive or that they are playing to existing strengths (see Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1. Countries with OGP Commitments in Rulemaking Transparency Receive Higher GIRG Scores

Source: GIRG database, N=78.

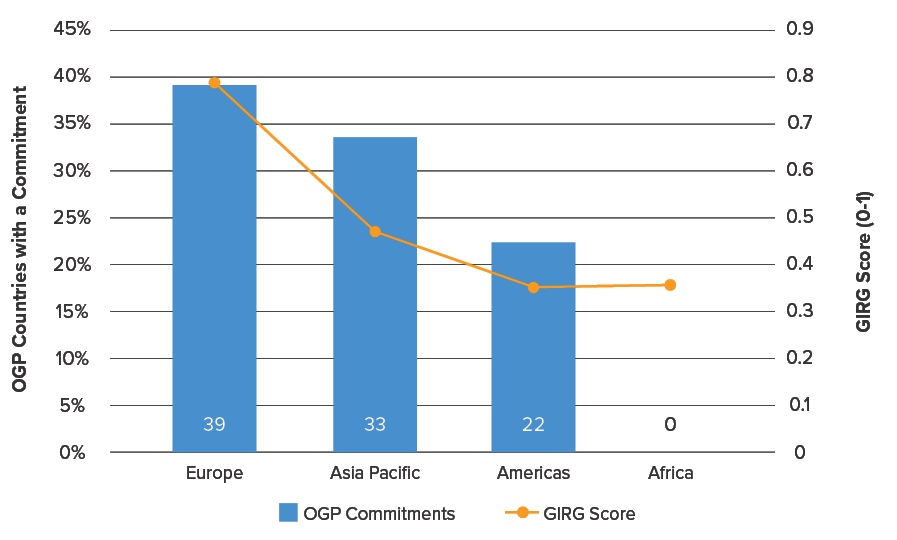

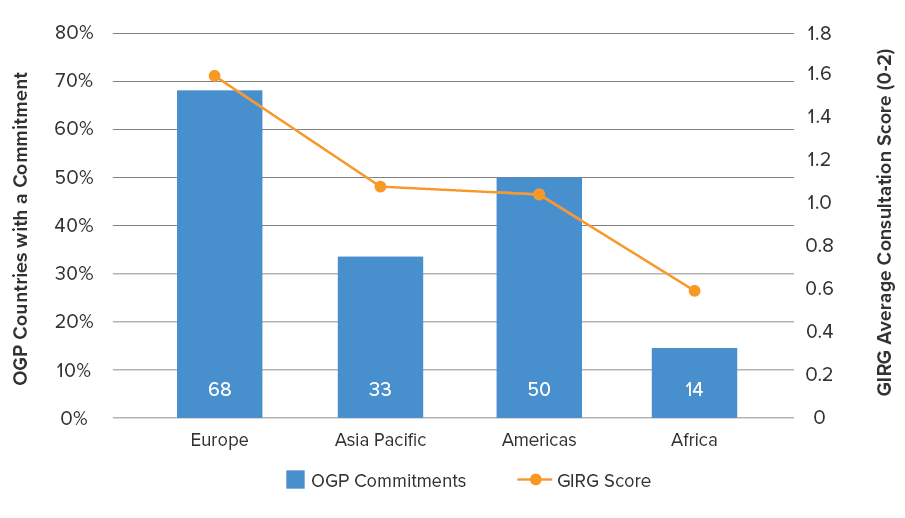

OGP countries in Europe have shown the most progress on transparent rulemaking

Across regions, countries in Europe have made the most OGP commitments to improve transparent rulemaking. Out of 31 sampled European countries, about a third have made OGP commitments to publish forward regulatory plans and score well on the GIRG’s regulatory transparency measure (see Figure 2.2). The general data trend indicates that countries that are already showing a good performance in the field of regulatory transparency are also the ones that are actively adopting transparent and inclusive rulemaking through their OGP commitments, such as the Netherlands:

- The Netherlands committed to digitizing government announcements. As of 2009, the Government Gazette, the Bulletin of Acts and Decrees, and the Treaties Series are published in e-format. Starting in 2014, other levels of the Dutch government, including local and provincial, committed to announcing their new regulations and regulatory changes through online publications.

Interesting to note is that some of the European countries that do not have a current commitment in this area already receive a maximum score on the GIRG’s transparency of rulemaking metric. This underscores how several countries do not need to make a specific OGP commitment given an already successful implementation of transparent rulemaking practices. At the same time, the data imply that other countries – such as Portugal, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Romania – have more room for improvement to meet the broader European standard.

Visual representation of the European Parliament’s Legislative Train that guides users through the legislative process. The tool can be found here: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/legislative-train/. Photo by: https://vimeo.com/184477380 Lessons from Reformers: The European Parliament’s Legislative Train The European Parliament’s Legislative Train is an interactive app and webpage that allows citizens to monitor progress on the EU Commission’s legislative priorities. The platform looks like a train schedule where each train represents a priority area and each carriage corresponds to individual legislative proposals. Users can use the platform to read about each proposal, find the current status of proposed legislation, and view monthly updates. The platform uses a simple key to indicate if draft laws have been submitted to Parliament for debate, adopted, delayed, or “derailed.” Although the platform was initially created in 2014 under Jean-Claude Juncker to monitor progress on his legislative priorities during his five-year term, the Parliament has since expanded the platform’s scope and continues to use it for its current term, which began in 2019. The Legislative Train is just one of many initiatives by the European Commission aimed at making law-making processes more open and effective. In 2015, the Commission presented its Better Regulation agenda, which looks to ensure that EU laws and regulations are high quality and fit-for-purpose, as well as created, adopted, and evaluated in consultation with citizens. Following the agenda, the Commission held over 400 public consultations and received millions of comments from Europeans on a variety of proposed policies and regulations. The Commission also established the Regulatory Scrutiny Board to standardize and improve impact assessments and other evaluation processes to ensure that existing regulations achieve their policy goals. |

Figure 2.2 Africa and the Americas Have Fewer Commitments in Transparent Rulemaking

Source: GIRG and OGP databases, N=78.

African countries in OGP lack commitments to improve regulatory transparency

None of the 14 African countries assessed have an OGP commitment in the field of transparent rulemaking. Among these African countries, only Morocco and South Africa received the highest possible score on the transparent rulemaking measure of the GIRG data set. Governments in both countries develop forward regulatory plans that include a public list of anticipated regulatory changes or proposals intended to be implemented within a specified time frame. And in both countries, forward regulatory plans are available to the general public through unified websites. South Africa serves as a particularly good example of participatory rulemaking on the continent:

- South African ministries and regulatory agencies publish annual reports outlining future policy developments. In addition to being available on a unified website, the reports are featured on specific websites of different ministries and regulatory agencies. For example, the reports are available on the websites of the Parliamentary Monitoring Group and the Department of Trade and Industry. To improve the soundness and accountability of regulatory systems on the African continent, countries are encouraged to use the OGP platform to identify viable commitments and frame short- and long-term reform efforts around these commitments.

Few countries in the Americas have made a commitment in this area

In the Americas, four out of 19 countries have actively committed to improving the transparency of rulemaking processes – Colombia, Canada, Guatemala, and the United States. Despite an already strong performance on regulatory transparency indicators, Canada has two commitments in this field, while the United States has three. Examples of countries in the Americas with commitments in this area include:

- Colombia has made a strong commitment to advance participatory rulemaking. On February 14, 2017, the government of Colombia issued a decree stipulating that drafts of all the regulations of the executive branch must be subject to a minimum of a 15-day public consultation period. Also, the new decree mandates every ministry and regulatory agency publish extensive forward regulatory plans for a period of at least 30 days. Now, the government of Colombia has committed to building a central platform for participation. To enhance regulatory transparency further, the government launched a digital app, MiSenado, through which citizens can access legal drafts.

- Guatemala, despite some setbacks, is striving to improve regulatory transparency. Guatemala committed to building public trust in rulemaking and making all legislative changes subject to stakeholder scrutiny before presenting them to Congress. A new feature on the website of Congress has allowed citizens to begin submitting comments on draft laws.

Despite stronger performance, more work is needed in Asia Pacific

Five of the fifteen countries from the Asia Pacific region have made an OGP commitment to systematically publish all notices of proposed rulemaking. Out of these five countries, Armenia receives the highest possible GIRG score on transparent rulemaking, followed by Georgia, the Kyrgyz Republic, and New Zealand. Examples of OGP commitments include:

- Georgia has yet to make forward regulatory plans public. The Parliamentary Secretary collects legislative plans from all of the ministries on a biannual basis and then puts together a comprehensive legislative action plan that is presented to the Parliament. However, forward-looking regulatory plans are not made publicly available. This is similar to the situation in the Kyrgyz Republic, where all ministries are required to develop internal nonpublic legislative agendas for secondary legislation.

- New Zealand publishes regulatory stewardship strategies. Most departments are responsible for developing individual forward regulatory plans. Subsequently, every department contributes to the development of the government’s annual legislative program – for primary laws. In general, these plans and programs are not made public. However, major regulatory departments do publish regulatory stewardship strategies that include regulatory plans within which they have stewardship responsibilities.

- Mongolia committed to making regulatory processes more transparent. Mongolia is yet to deliver on its commitment to making the draft laws, acts, amendments, and administrative rules open to the public. In particular, the government aims to make regulatory information publicly available through “Public Service Online Machines,” Citizens Chambers, and public libraries at each provincial level.

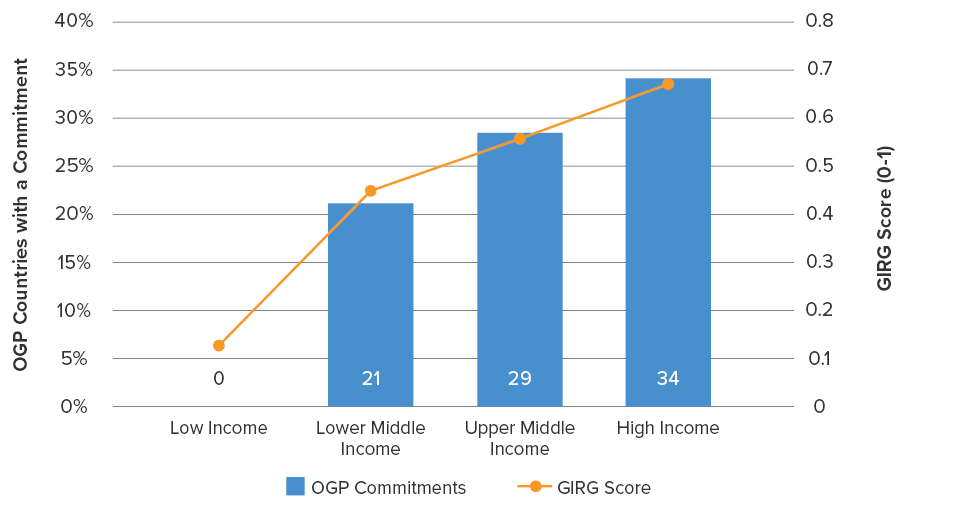

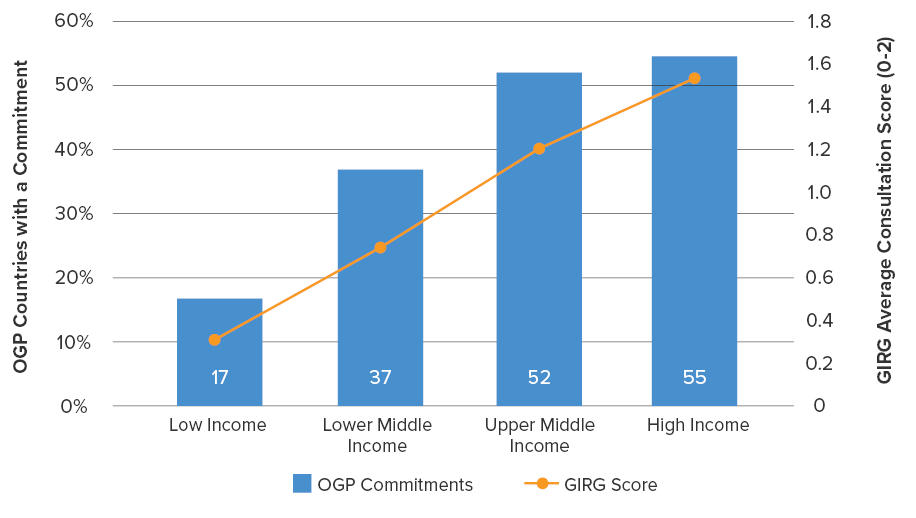

The performance gap is evident between high- to upper-middle-income and low-income countries

High- and upper-middle-income countries generally perform strongly, but not uniformly. Many of these countries’ OGP commitments are driven by the European Union’s and the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s (OECD) mandates. Countries from these two income cohorts also tend to score better on the GIRG measures (see Figure 2.3). Arguably, rich economies have more resources (human and financial), administrative capacity, and requisite legal expertise to undertake and effectively implement reforms. They also benefit from more advanced use of information technology. In the case of the OECD, all members now employ some form of regulatory impact analysis, which may play a role. However, well-to-do countries still have considerable room for improvement. Specifically, seven high- and upper-middle-income countries score poorly on the GIRG measure and have not made a commitment through OGP to address the gap.