Introduction

Broken Links: Open Data to Advance Accountability and Combat Corruption offers an overview of the state of open data against political corruption in Open Government Partnership (OGP) countries. Using new data from the Global Data Barometer, the report explores trends across nine policy areas, identifies areas for improvement, and provides recommendations for future OGP commitments.

This report identifies both where OGP countries are doing well and where they need to improve—examining, for example, which governments disclose who lobbies them; whether political parties and candidates reveal their donors; and whether the public is able to see who owns anonymous companies so often used to launder money. The report also looks at the measures needed to further link to people and other important data, creating a chain of accountability.

Broken Links explores these critical areas and identifies trends at the country, regional, and global levels. The four core pieces of the report, along with their common use cases, are:

- Global findings: Understand global challenges and opportunities.

- Policy area findings: Discover value propositions, stories, and recommendations.

- Regional findings: See progress and examples from neighbors and similar countries.

- Data Explorer (including country findings): Identify what data a country or region does (and does not) publish.

Explore the Data

See what data a country or region does (or does not) publish using the Data Explorer »

Download the Report

Download the executive summary and explore regional modules (including subregional modules not included in the full report) here »

Executive Summary

Background

In March 2022, Czech prosecutors announced that former Czech Prime Minister Andrej Babiš would face charges of fraud for allegedly pocketing millions of euros in EU agricultural subsidies. This marks another high-profile case of potential political corruption—and it adds to a growing global trend that threatens to skew resources and policies away from the common good, perpetuating inequality and undermining democracy. So what can be done? What will ensure that governments serve the public interest rather than the affluent or well-connected few?

The answer is that no single reform is enough. Several layers of accountability are needed, from independent oversight bodies to investigative journalists and an active civil society. However, one fundamental, underlying layer must always be present: making information public through open data. Open data on how decisions are made, what officials own, and whose interests they serve can shine a light on political corruption and help make political systems fairer and more inclusive.

This data is the focus of this report. Drawing on a new global study, the report provides the most complete picture yet of the state of open data against political corruption—across nine policy areas (see Table 1) in 67 countries participating in the Open Government Partnership (OGP).

This report identifies both where these countries are doing well and where they need to improve—examining, for example, which governments disclose who lobbies them; whether political parties and candidates reveal their donors; and whether the public is able to see who owns anonymous companies so often used to launder money. The report explores these critical areas and others identifying trends at the country, regional, and global levels.

However, the report does not stop at what data needs to be made public. It looks at the measures needed to further link to people and other important data, creating a chain of accountability. The public and institutions working together give data its power.

That is why this report is called Broken Links: Open Data to Advance Accountability and Combat Corruption. As the case of Andre Babiš shows, no single dataset, actor, or sector can alone solve the problem of corruption. But linked together—across borders, levels of government, and parts of society—data becomes a powerful and a fundamental means for change.

Table 1. Policy areas covered in this report

Asset Disclosure: Data on assets, liabilities, and finances of elected and senior-appointed officials and associates. | Political Finance: Data on financial flows to and from political parties, candidates, and third parties, including income, expenses, and donations. |

Company Beneficial Ownership: Data on people who own, control, or benefit from companies, including the nature and size of the interest they hold. | Land Ownership and Tenure: Data on who owns land and the type of tenure – including state, communal, and open access lands. Land is a subject of major policy decisions and a means of hiding illicit enrichment. |

Public Procurement: Data on the purchase of goods, services, and public works, including names of suppliers, dates, costs, and details on each stage of the contracting cycle. | Lobbying: Data on who influences policies and decisions, including details of interactions with public officials such as dates and times, topics, and money spent. |

Right to Information (RTI) Performance: Data on the implementation of RTI laws, including the number of requests, delays, denials, and appeals. | Rulemaking: Data on the process of drafting regulations, including proposed regulations, public comments, reasoned responses, final regulations and justification, and challenges. |

Interoperability: Data on the linkages between datasets, such as through common identifiers for companies, legislation and regulation, public officials, and lobbyists. | |

Global Findings

Five Key Data Gaps

In its most simple terms, this report shows that very few countries actually publish the most important data to counter political corruption. Where public datasets exist, they are isolated and disconnected from others that would reveal the flow of funds and influence. These global challenges can be summarized in the form of five key data gaps: collection, publication, high-value elements, usability, and interoperability:

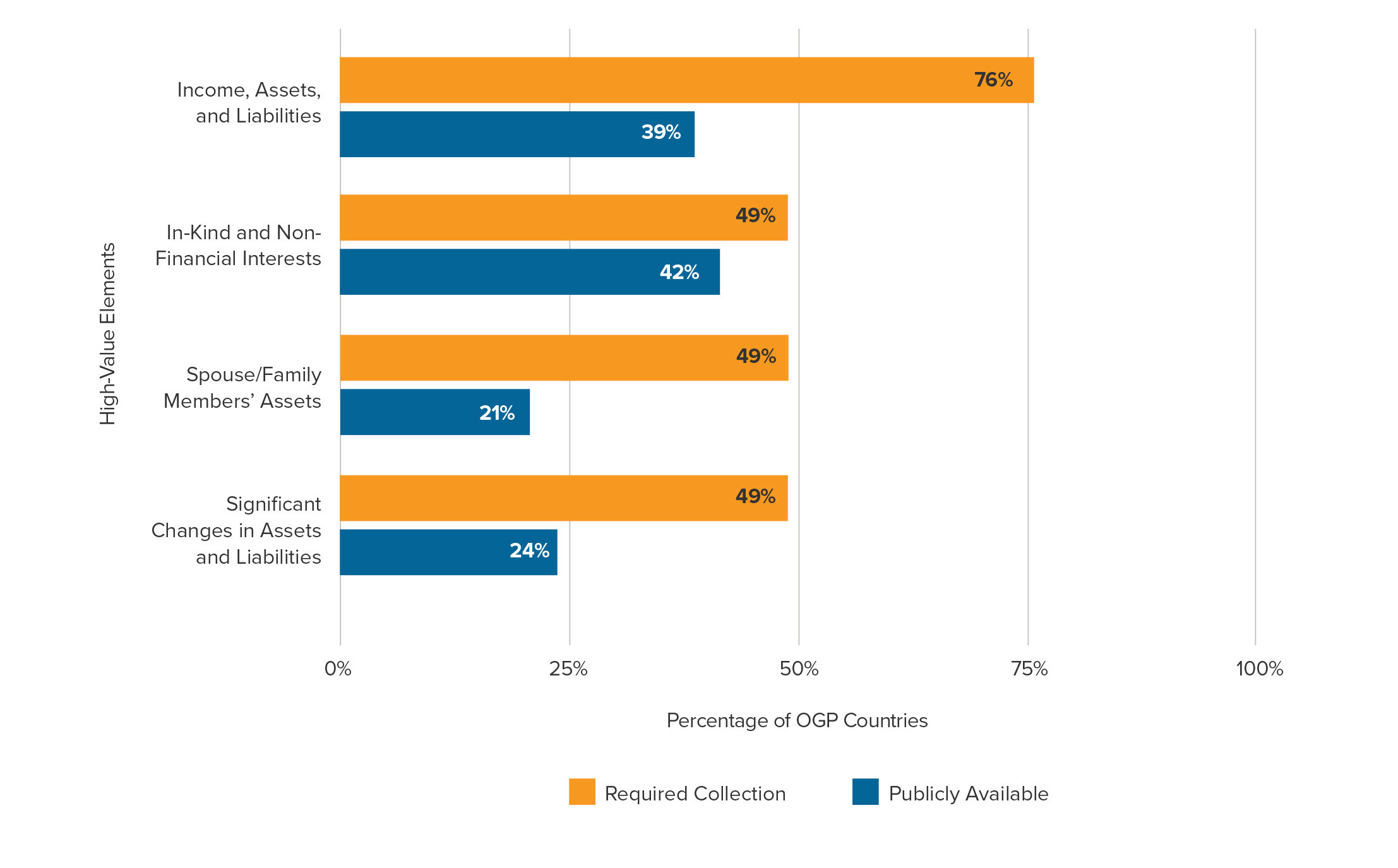

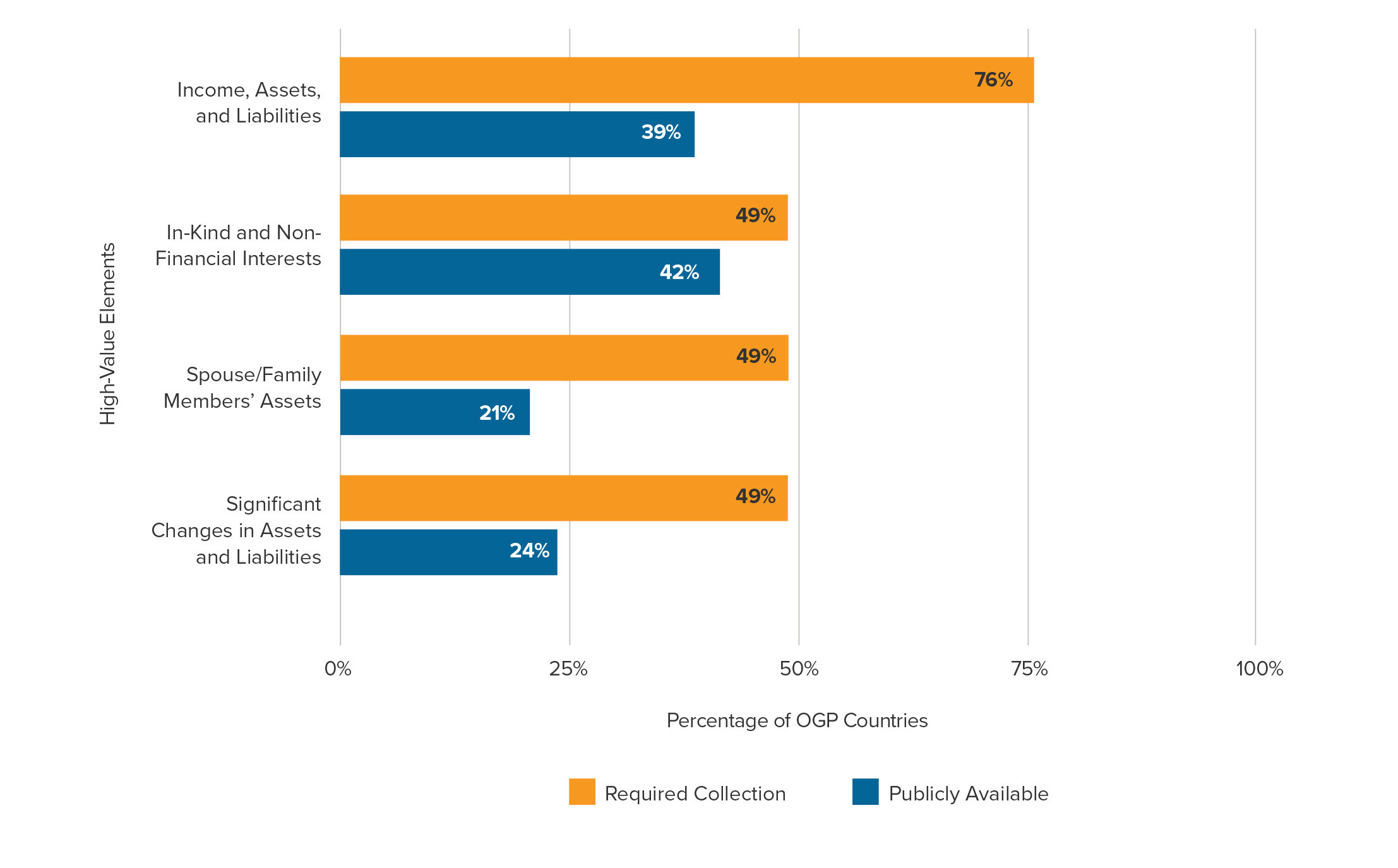

- Collection gaps: Many countries do not have laws or regulations mandating the collection of data, most notably as it relates to lobbying, but in other areas as well. Many high-value pieces of information, in particular, are not collected. For example, although all OGP countries require public officials to submit asset declarations, fewer than half require the same for other politically exposed persons, like spouses and family members.

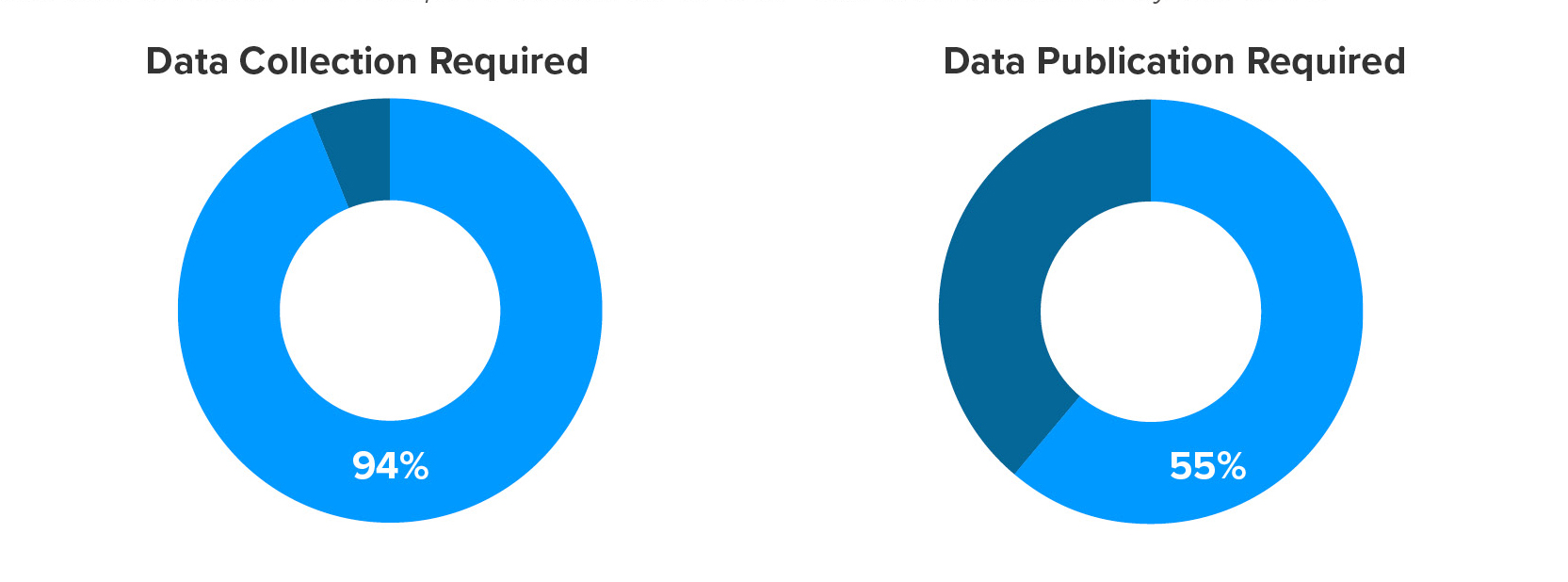

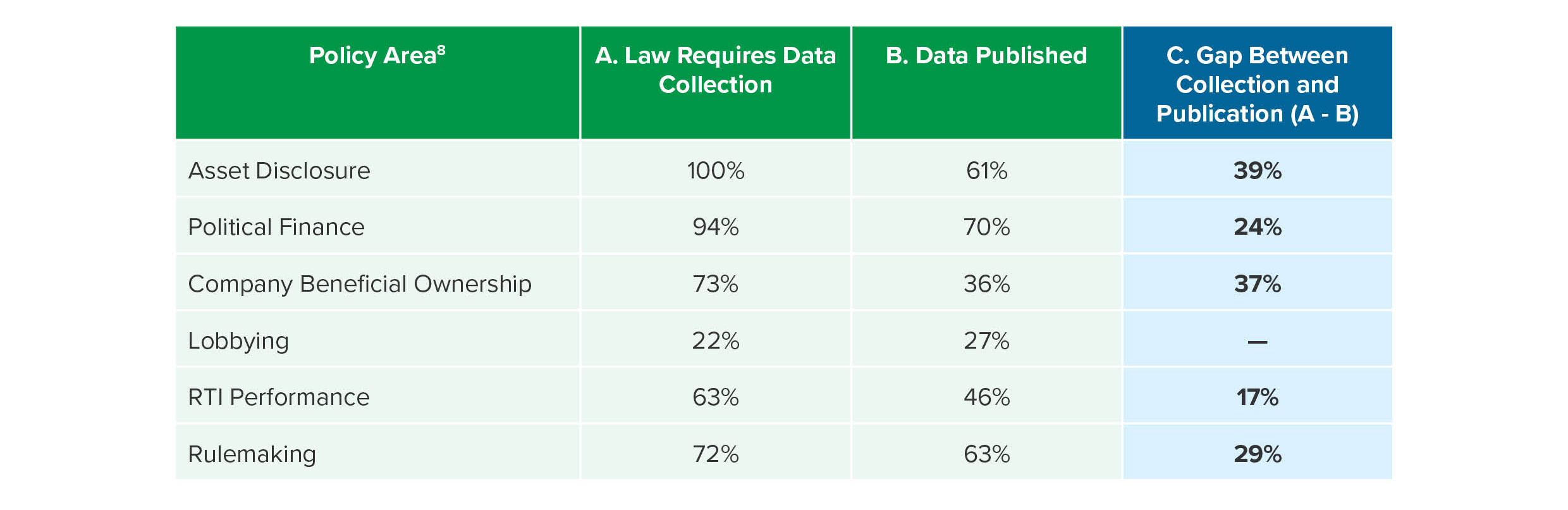

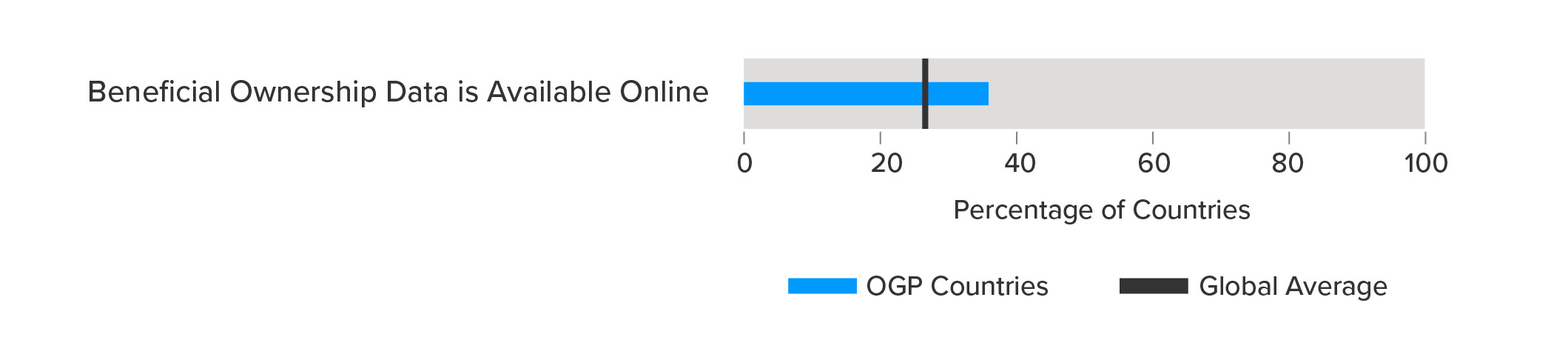

- Publication gaps: Many countries do not publish any data, even if data collection is legally required. For instance, only about one in three OGP countries publish any data on beneficial owners, despite most requiring it be collected. Across nearly all policy areas, the countries that mandate data collection far outnumber those that actually publish any data.

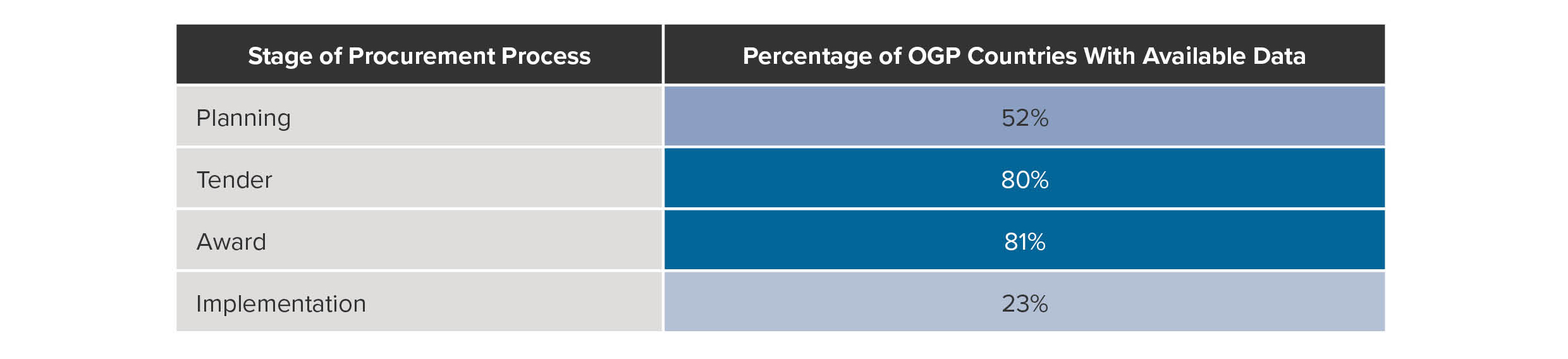

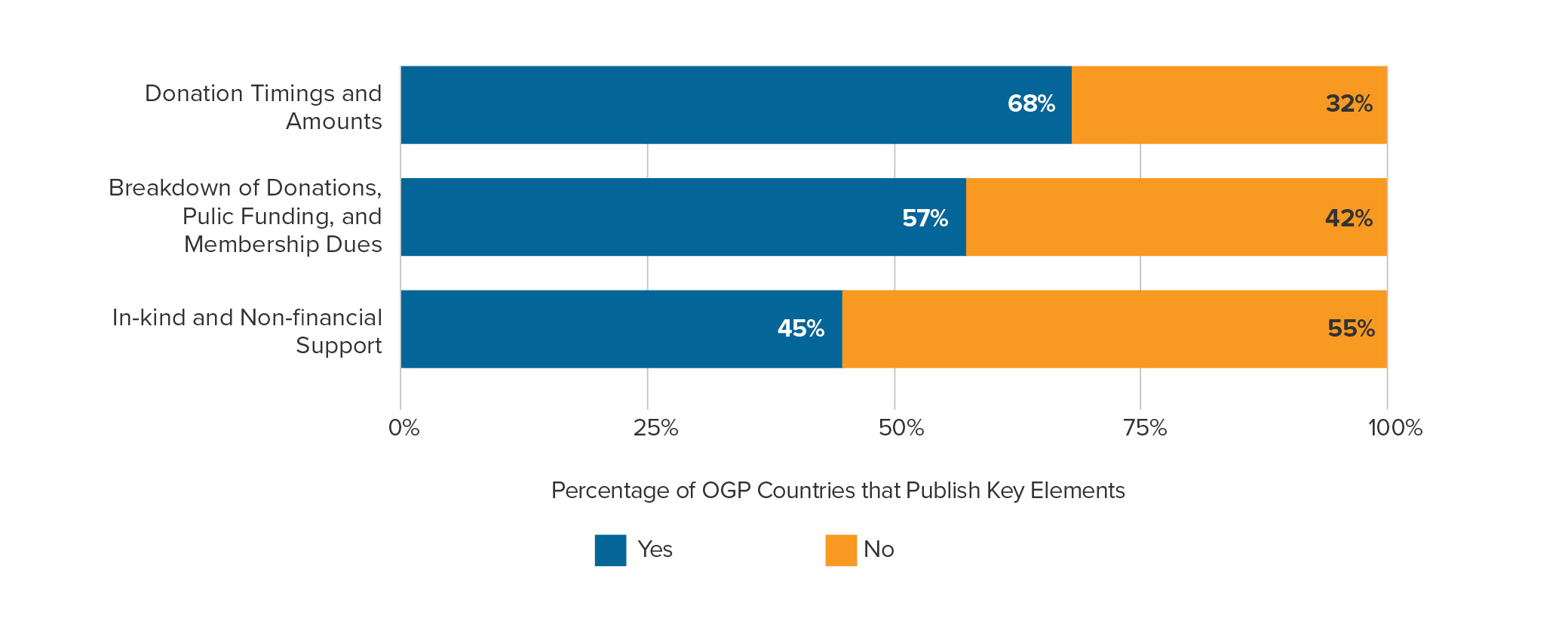

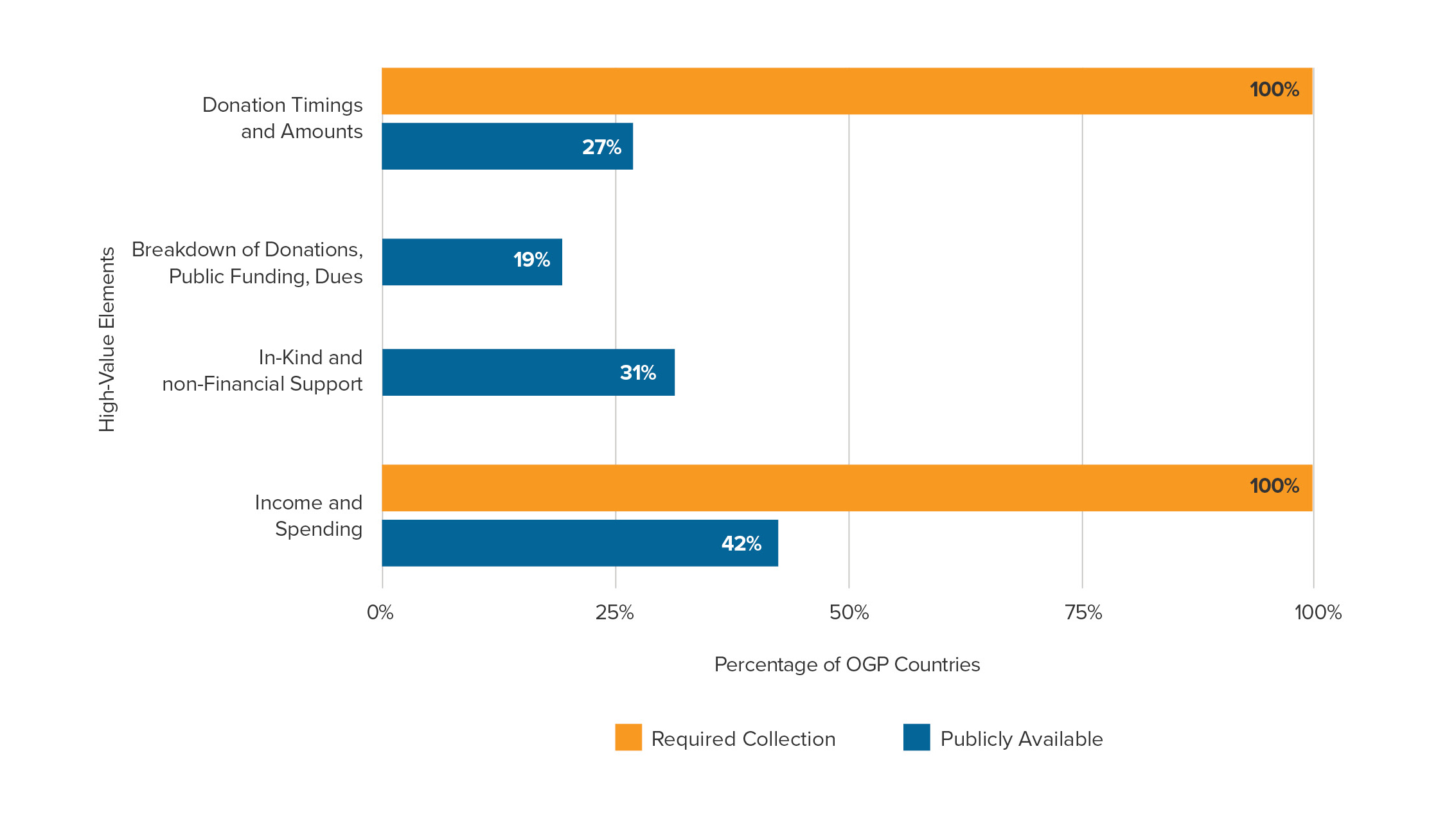

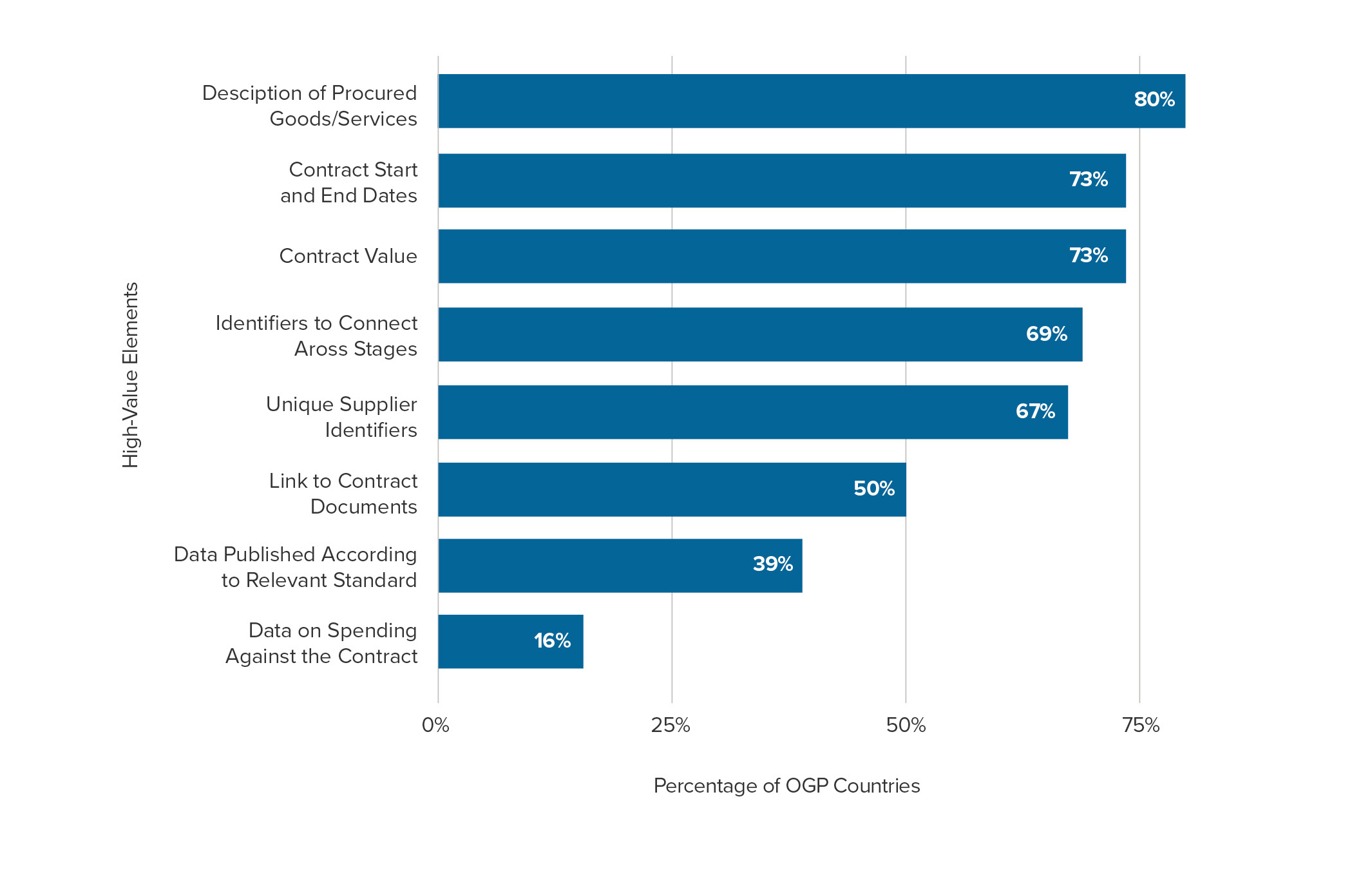

- High-value data gaps: Publishing data is not inherently useful; the data must include high-value elements that enable effective oversight. For example, although most OGP countries publish data on tenders and awards for public contracts, few publish information on contract implementation. Similarly, most OGP countries publish basic political finance data, but few clearly identify donors to political parties and candidates.

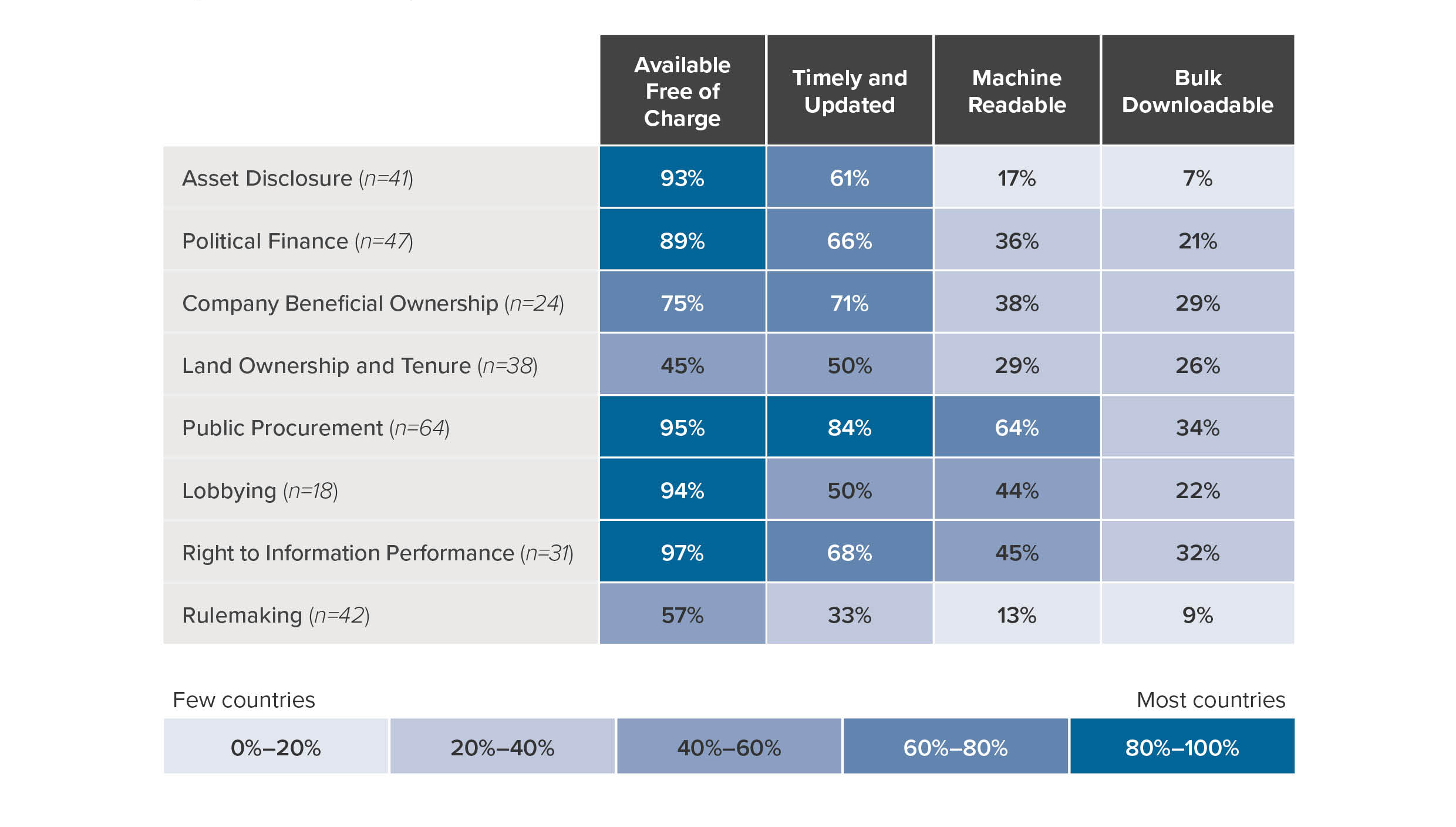

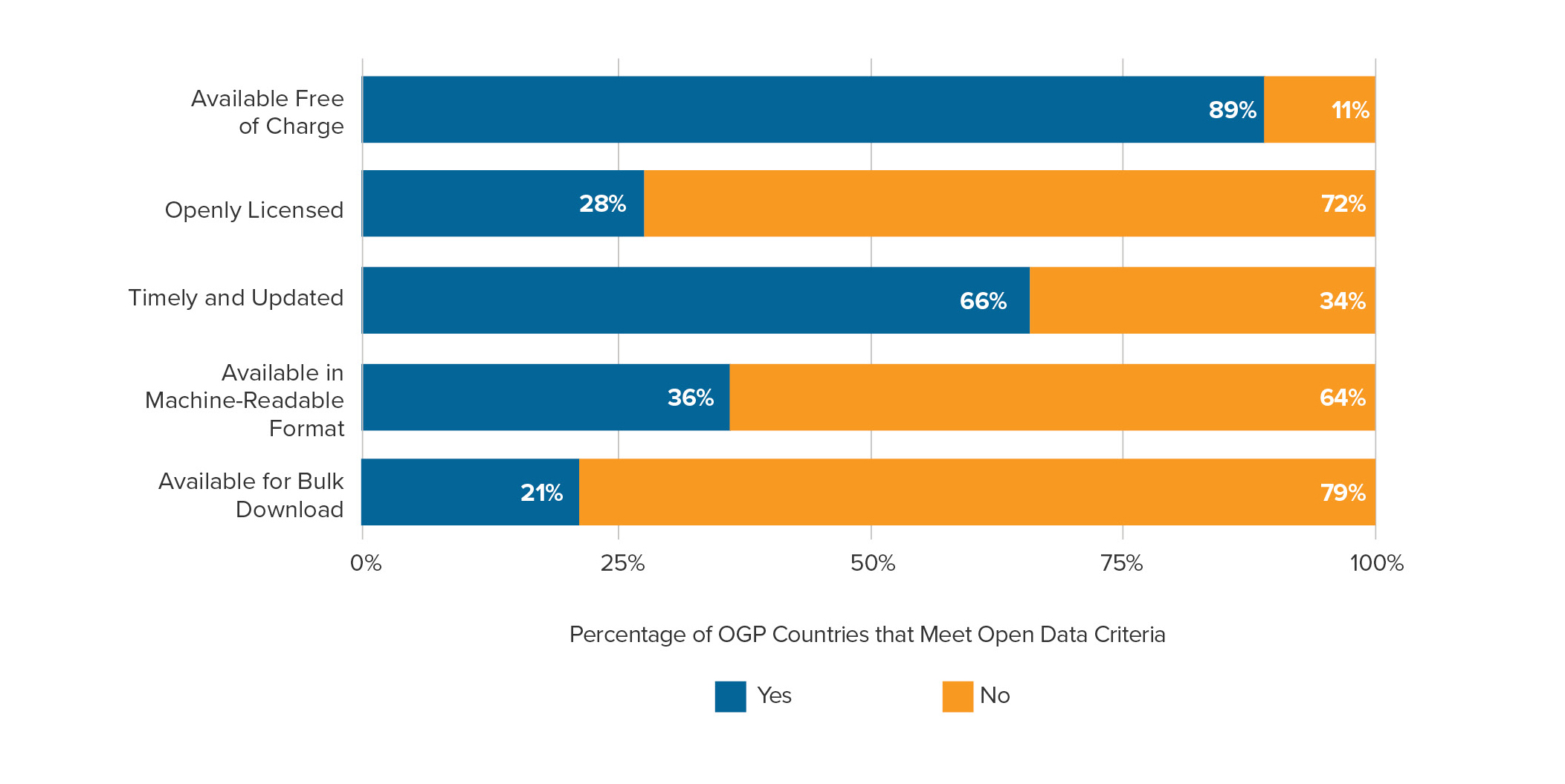

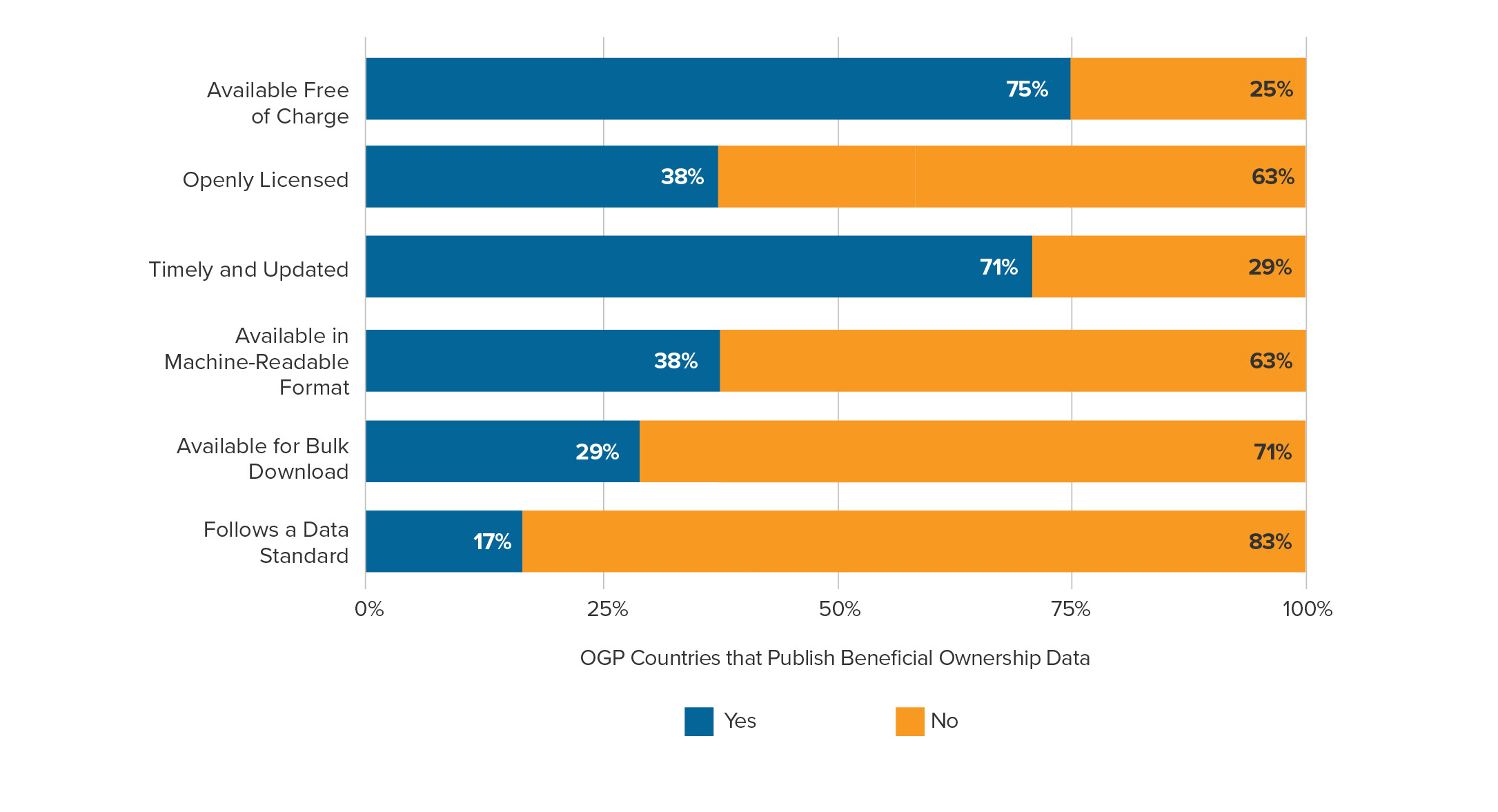

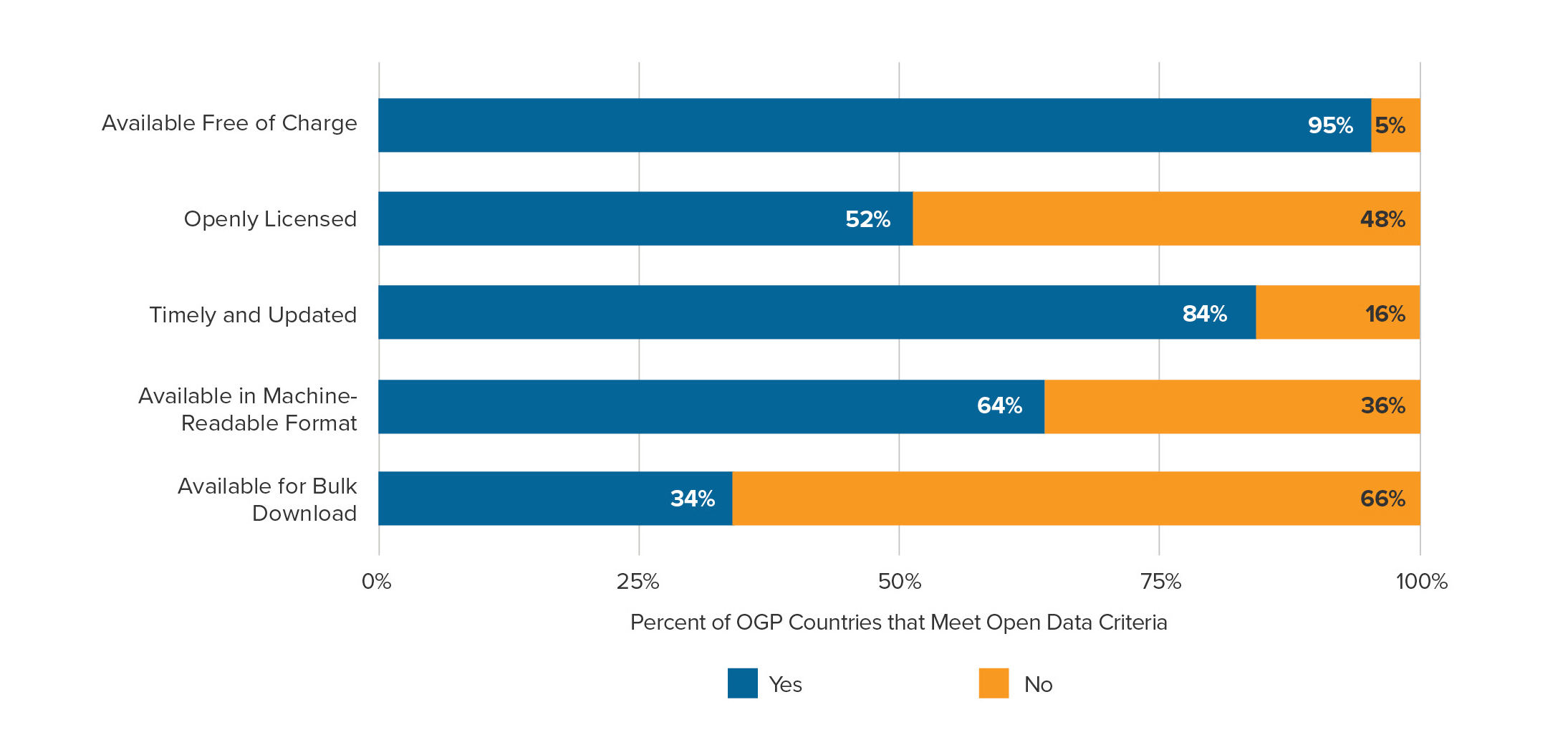

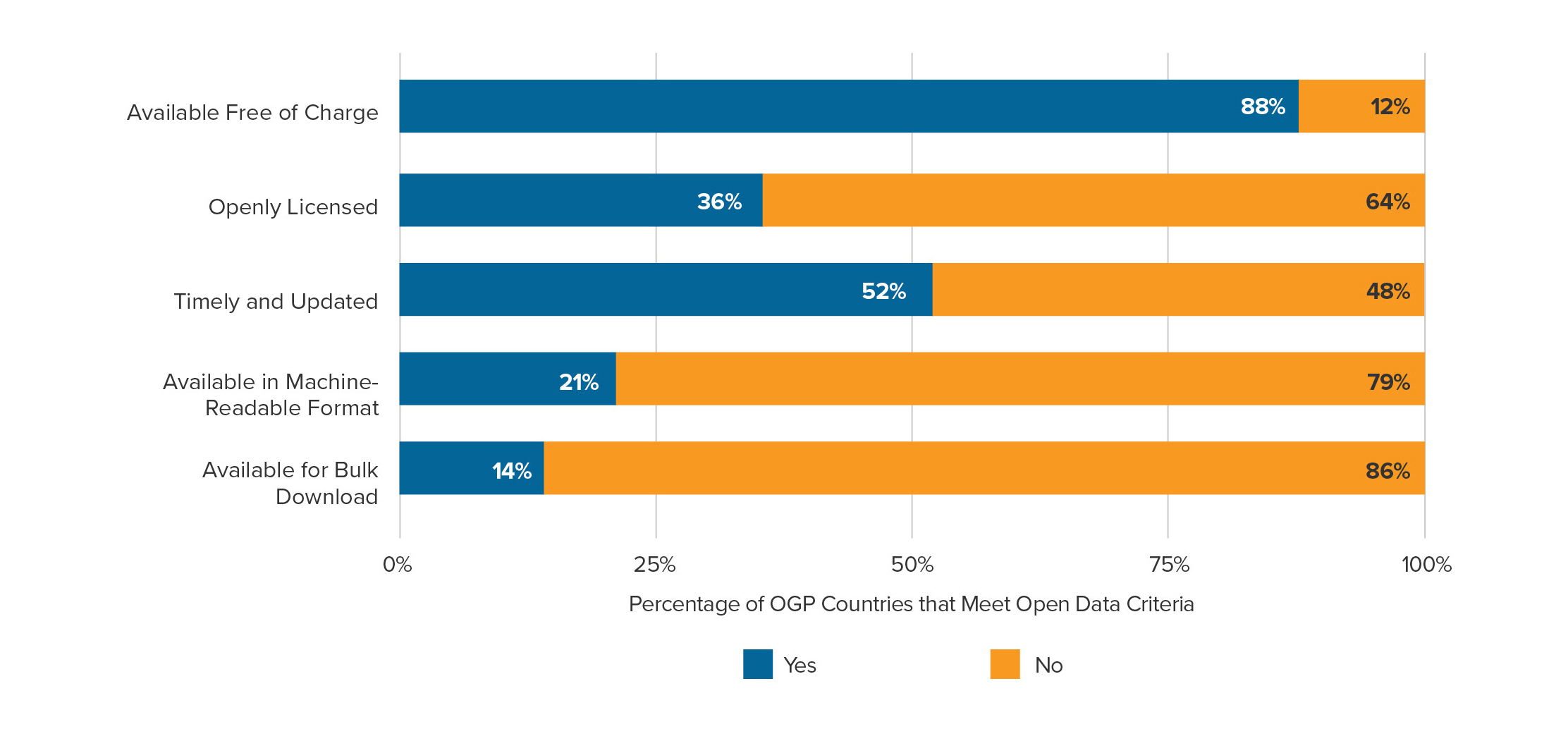

- Usability gaps: Few datasets meet open data standards. Although most datasets are available at no cost, most are not regularly updated or available in structured formats (as opposed to scanned forms and documents). This means that, even where available online, existing data is difficult to analyze.

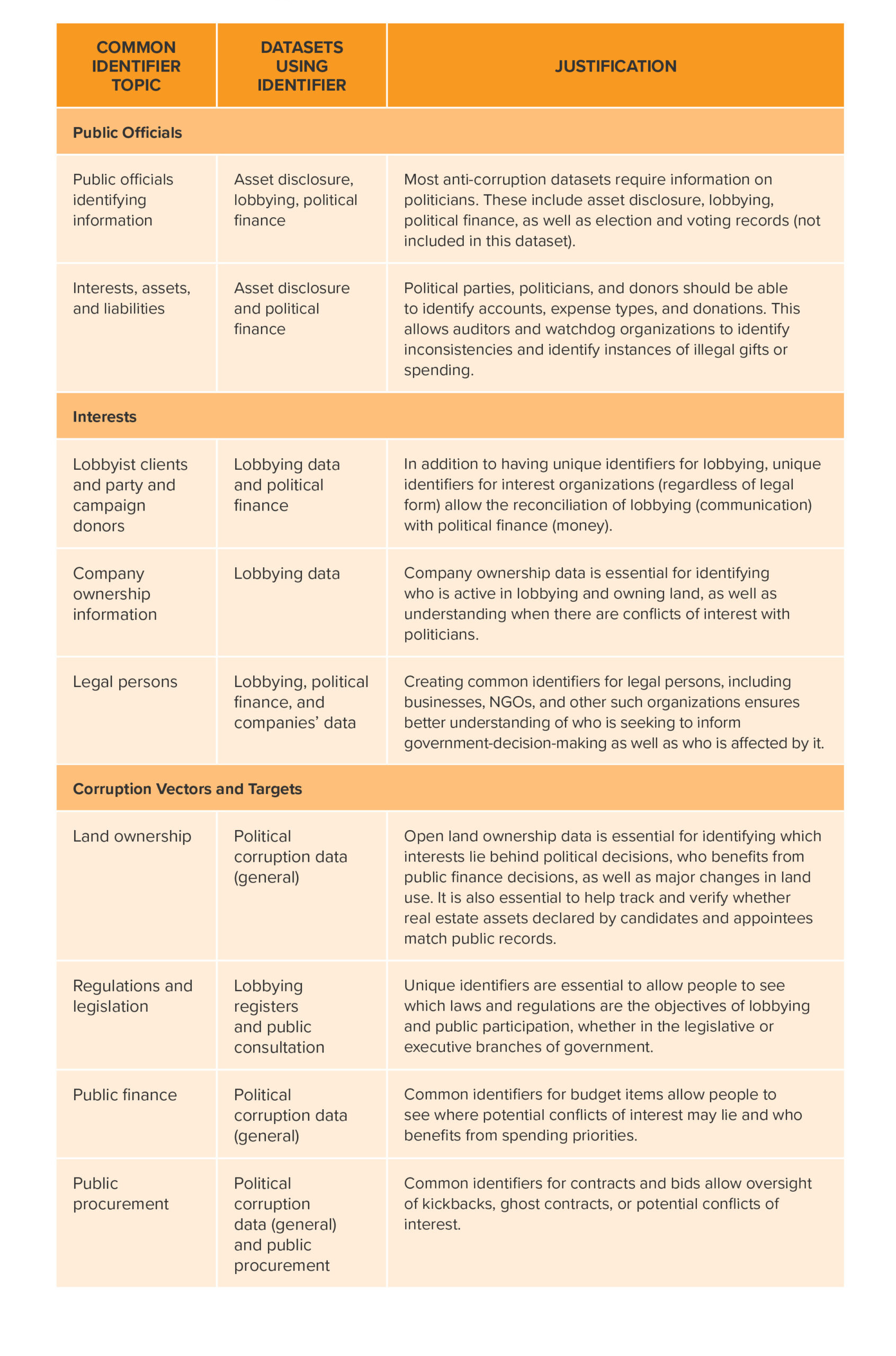

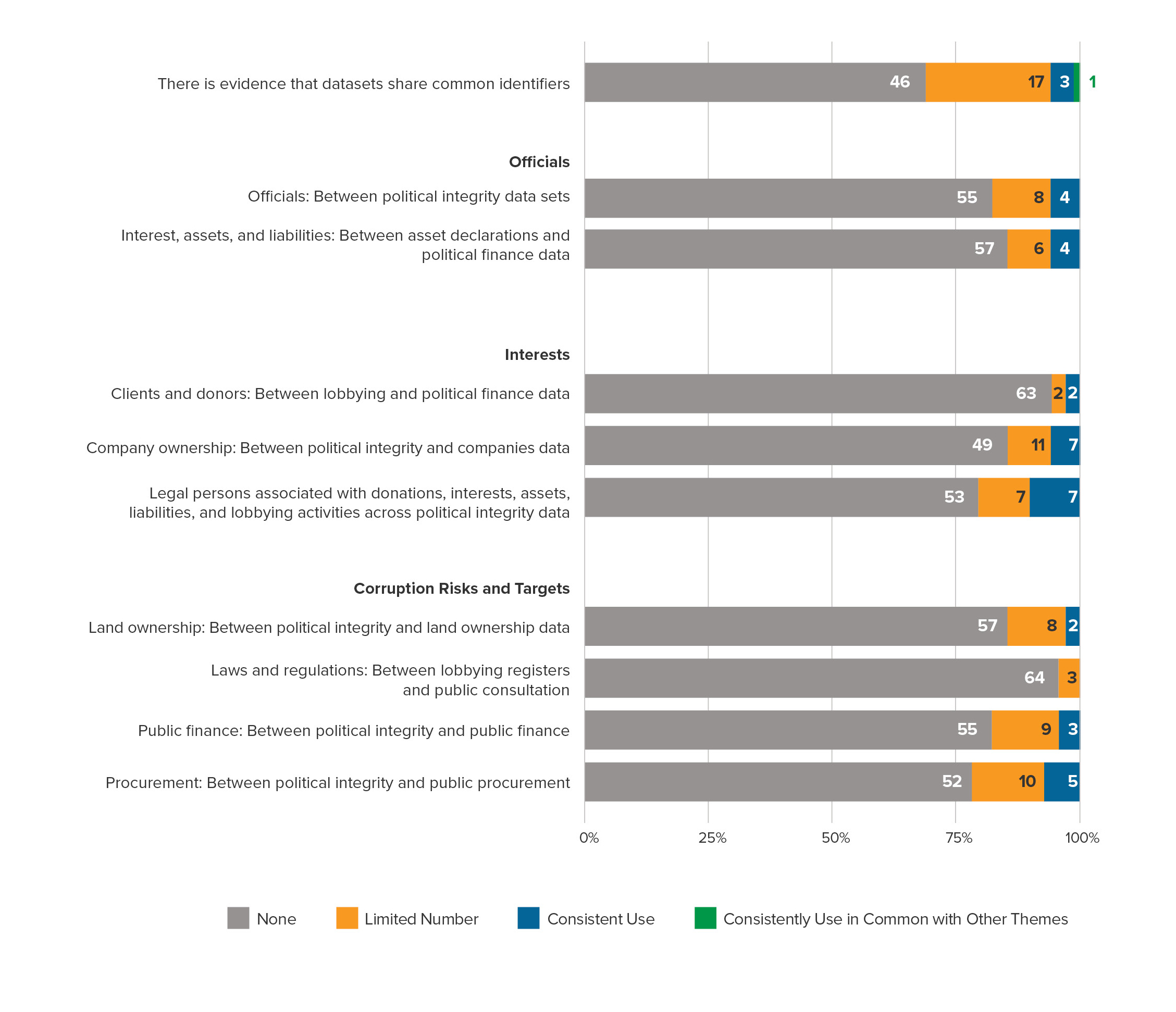

- Interoperability gaps: Combining datasets across policy areas increases the effectiveness of any single dataset. In the Babiš case, a series of linked datasets were used to identify the alleged fraud, including data on company ownership, land tenure, subsidies, and public contracts. However, most datasets lack common identifiers for companies, legislation, politicians, or lobbyists that would more easily enable identifying networks of corruption or undue influence. It is also important for people and institutions to exchange information, especially across sectors. As the cases in this report also show, the links between journalists, accountability institutions, and civil society organizations make all the difference in combating corruption.

Policy Area Findings

Varying Levels of Maturity

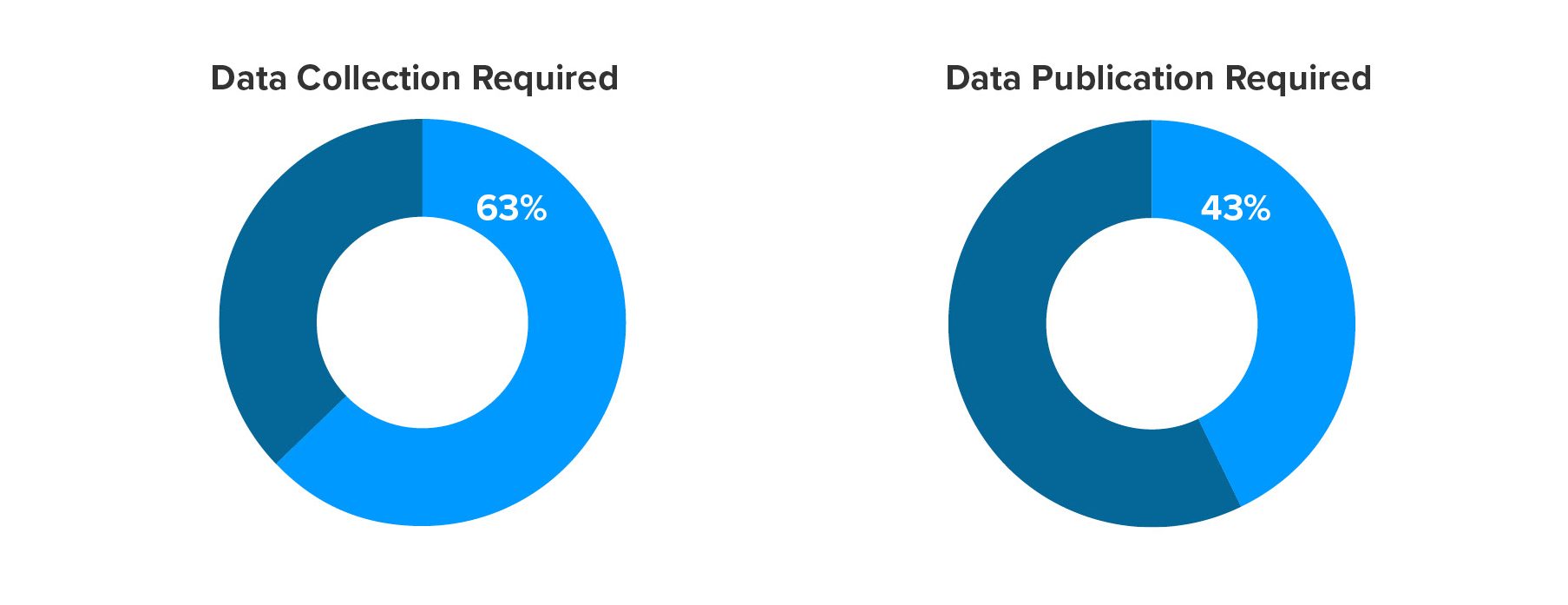

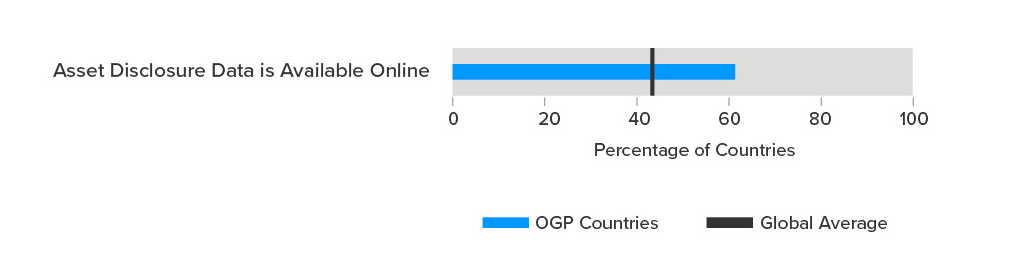

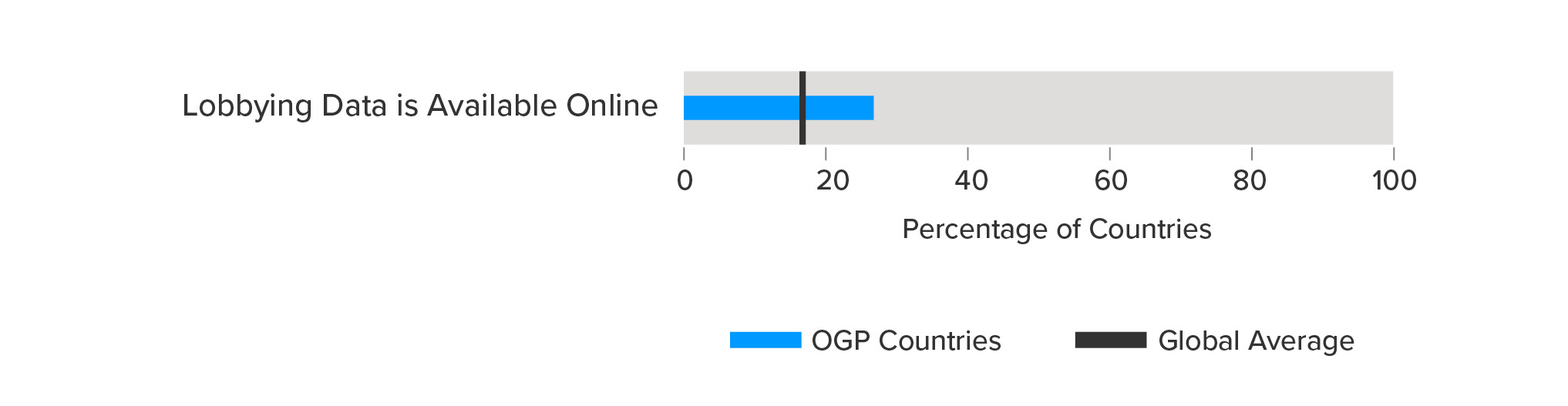

The global data gaps exist to varying extents depending on the policy area. For example, most OGP countries (96 percent) publish at least some public procurement data online, and most of these datasets include high-value elements in open data formats (see Table 2). On the other end of the spectrum, only a quarter of OGP countries publish any lobbying data, with even fewer legally requiring its collection. Levels of maturity, therefore, vary significantly by policy area.

Table 2. Varying levels of open data maturity by policy area (n=67)

The table shows the percentage of OGP countries that meet key data metrics for each policy area.

Data Collection Required | Data Published | High-Value Data Published † | Open Data Published †† | |

Asset Disclosure | 100% | 61% | 37% | 22% |

Political Finance | 94% | 70% | 39% | 39% |

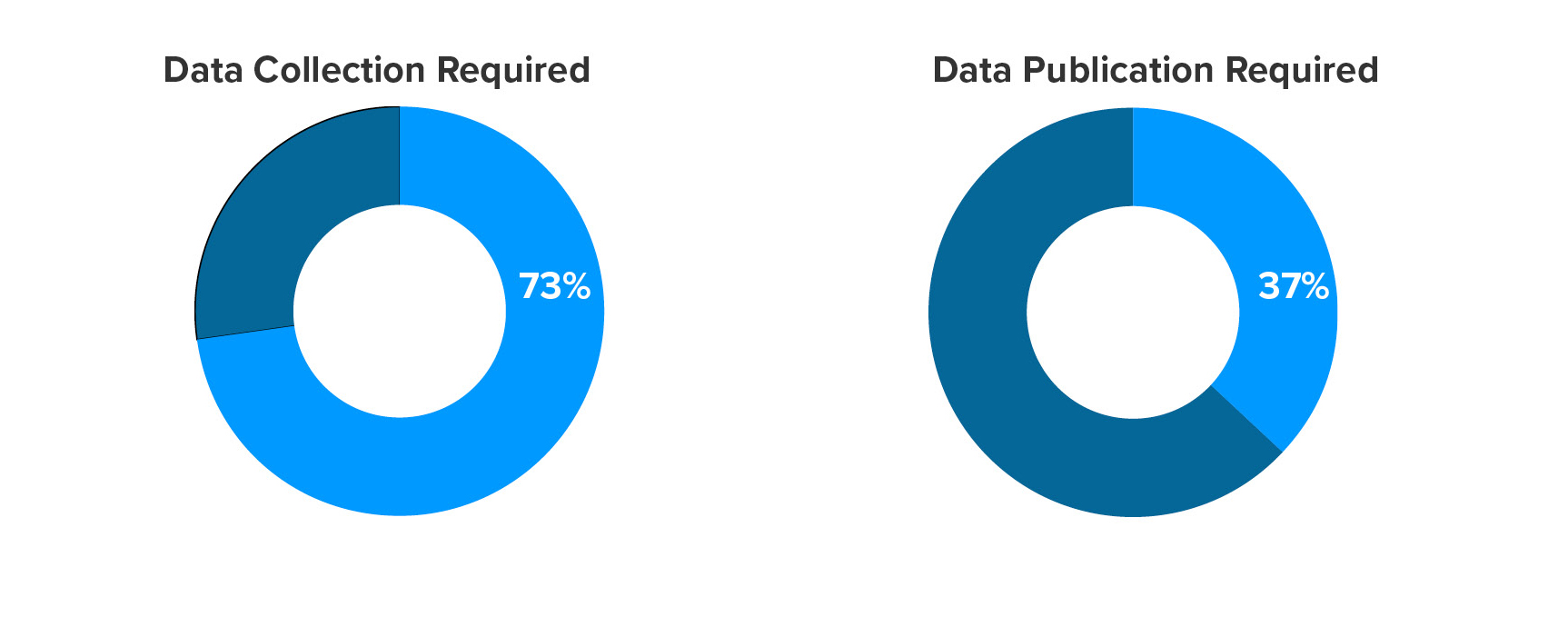

Company Beneficial Ownership | 73% | 36% | 19% | 21% |

Land Ownership and Tenure | Not reviewed | 57% | 19% | 16% |

Public Procurement | 96% | 69% | 67% | |

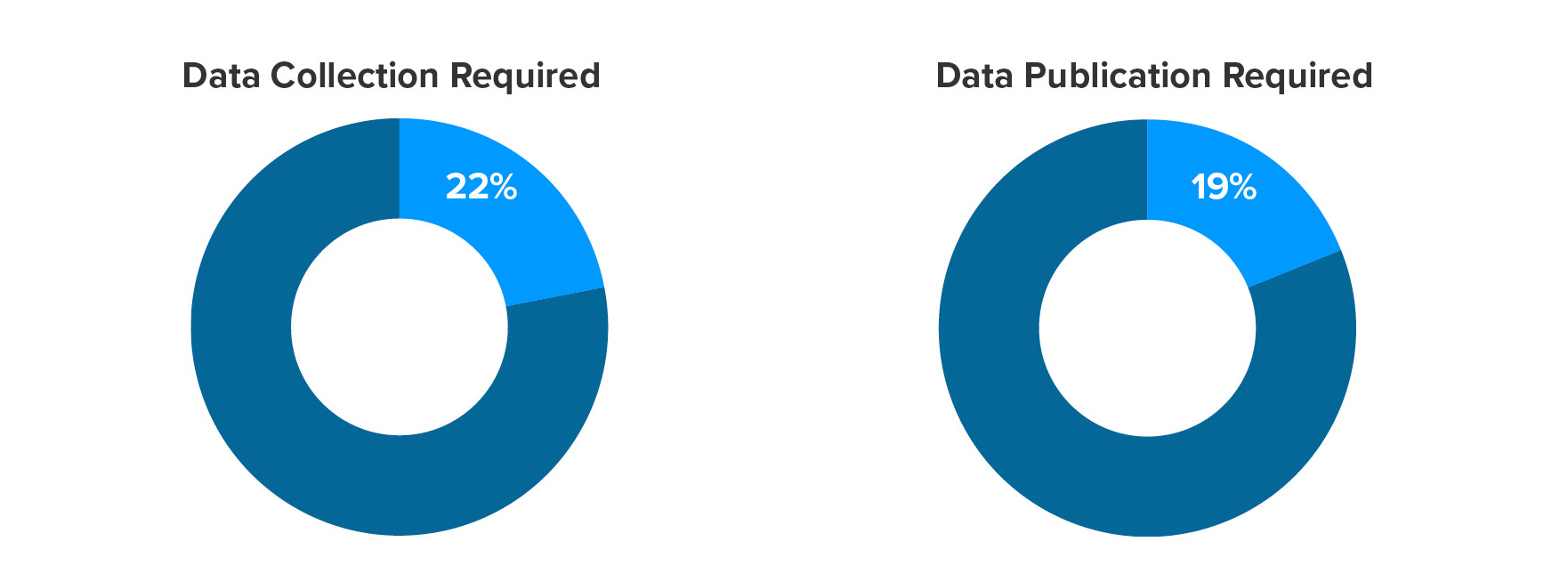

Lobbying | 22% | 27% | 7% | 10% |

Right to Information Performance | 63% | 46% | 27% | 25% |

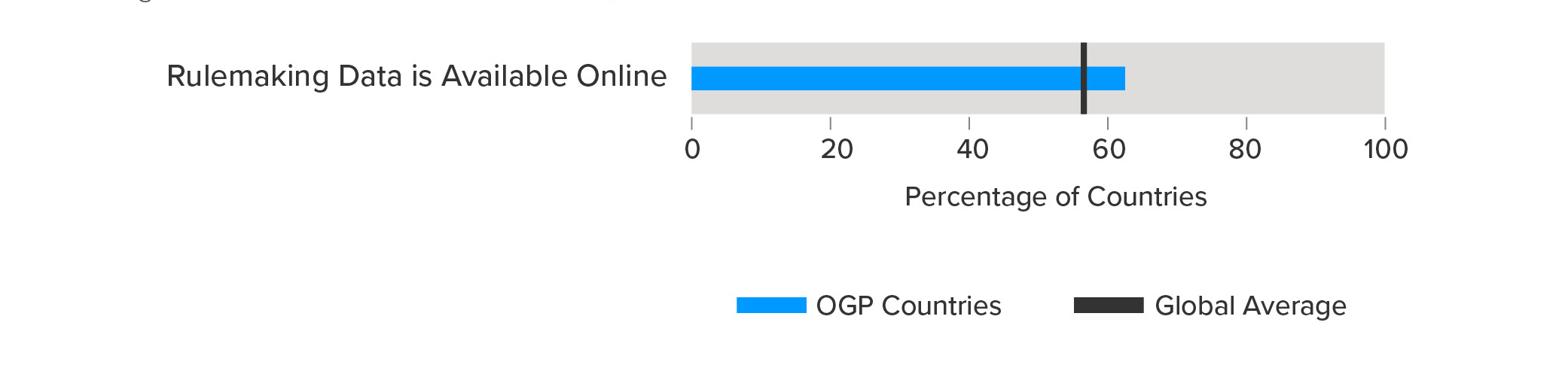

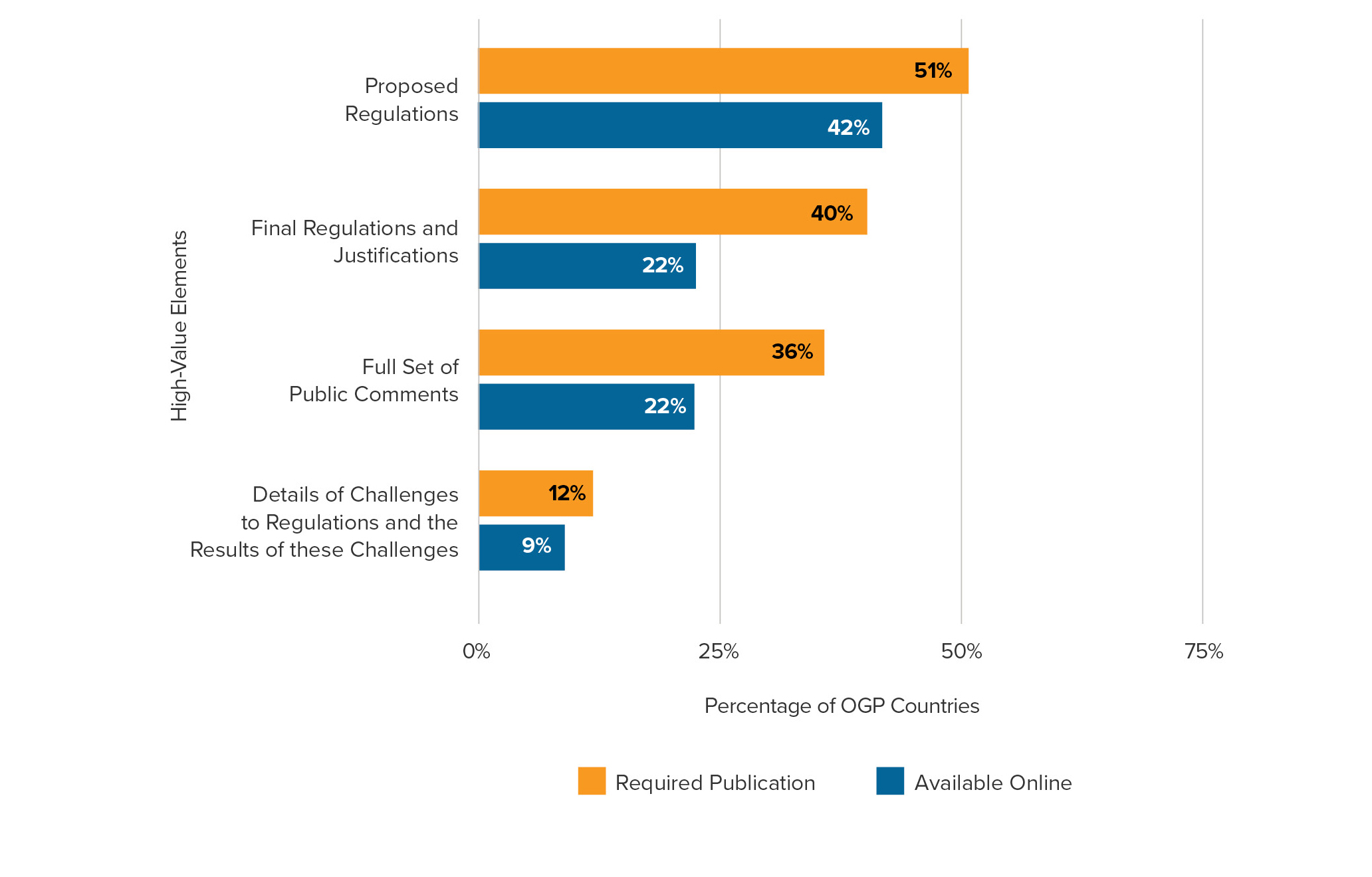

Rulemaking | 72% | 63% | 22% | 16% |

† A majority of high-value data elements are available online. See Annex for list of high-value data elements.

†† Published data meets most of the following standards: free, timely, machine-readable, openly licensed, bulk downloadable.

Few Countries | Most Countries | ||||

0%–20% | 20%–40% | 40%–60% | 60%–80% | 80%–100% | |

One exception is the publication of high-value data, as it is largely absent across all policy areas. These high-value elements are different for each policy area and critical for accountability. For example, most OGP countries publish which goods and services are being procured, but very few publish information on spending against contracts, which is essential for monitoring results. Table 3 summarizes which high-value elements are, and are not, generally available for each policy area.

Table 3. Availability of high-value elements by policy area

Policy Area | Summary of Findings |

Asset Disclosure | Most datasets include income, assets, and liabilities of certain public officials, but few cover close family members or significant changes over time. |

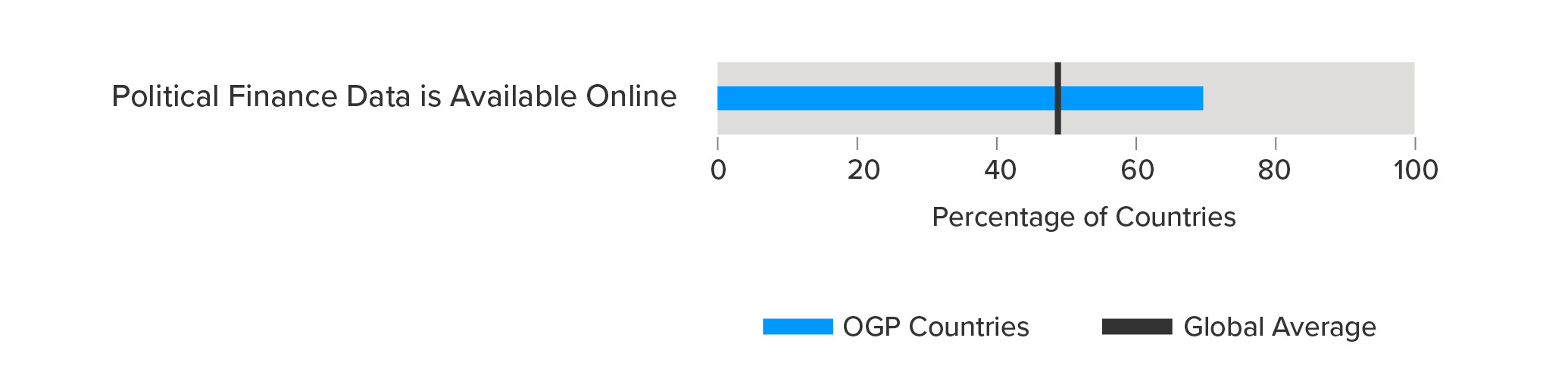

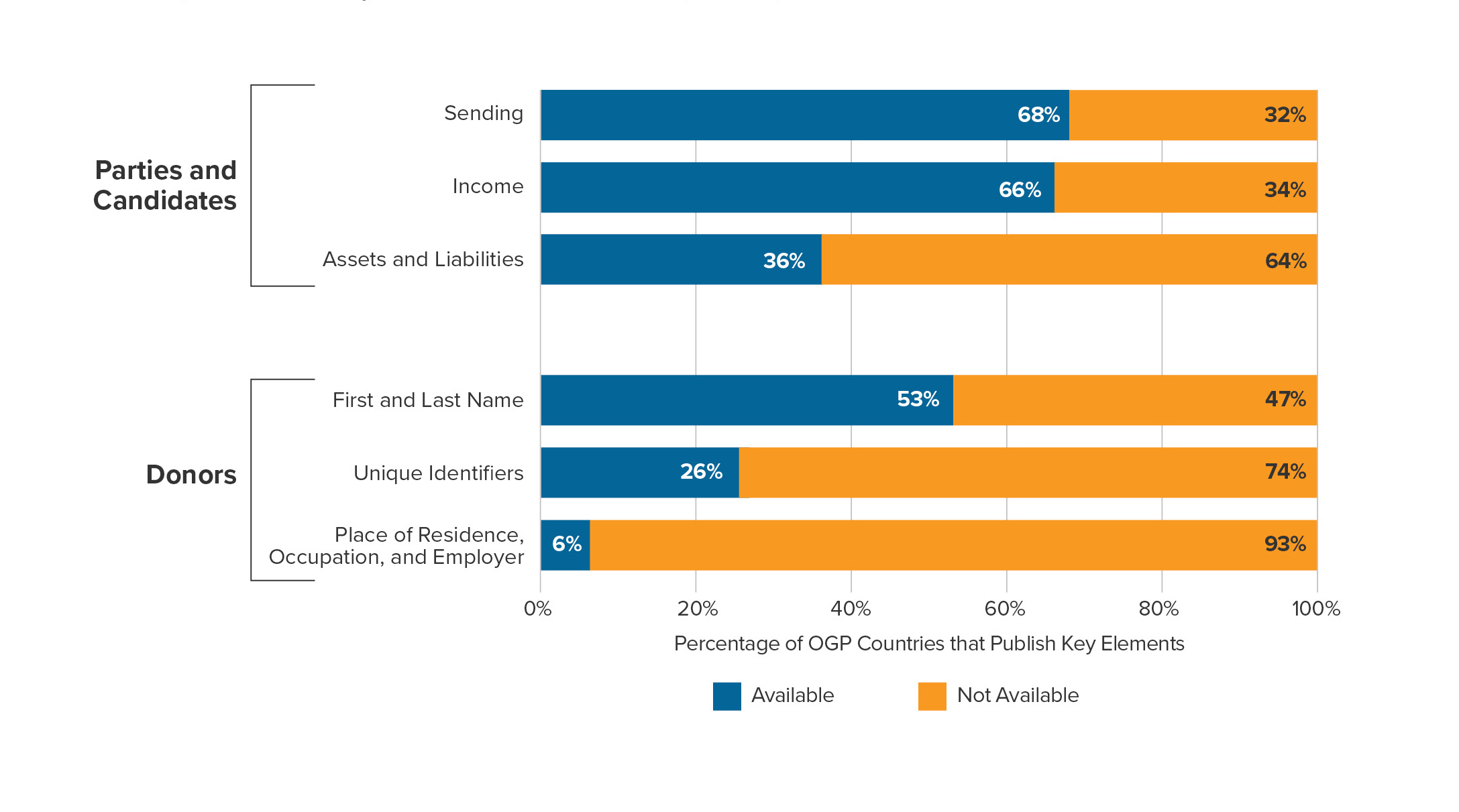

Political Finance | Two-thirds of datasets include income and spending of political parties and candidates, but few datasets cover assets and liabilities or clearly identify donors. |

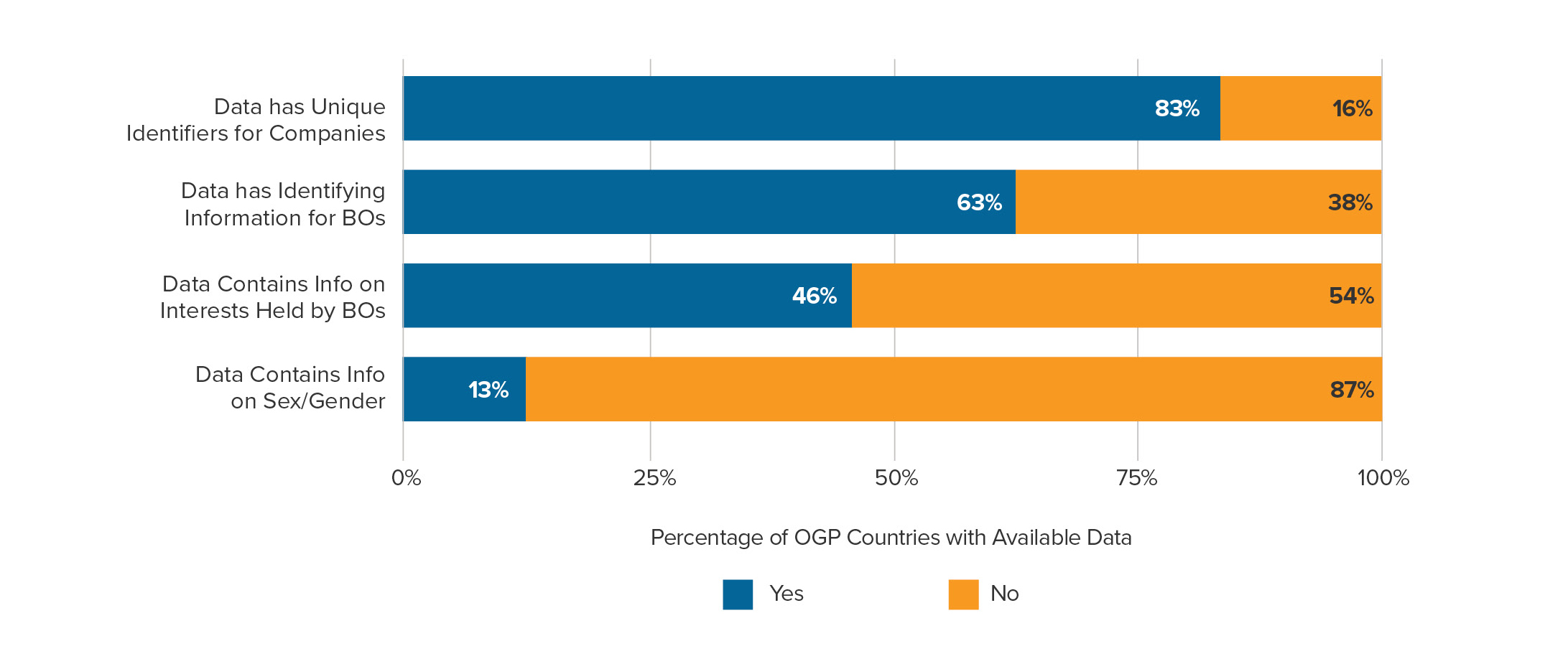

Company Beneficial Ownership | Most datasets include unique identifiers for companies and clearly identify owners, but few datasets specify the financial interests held. |

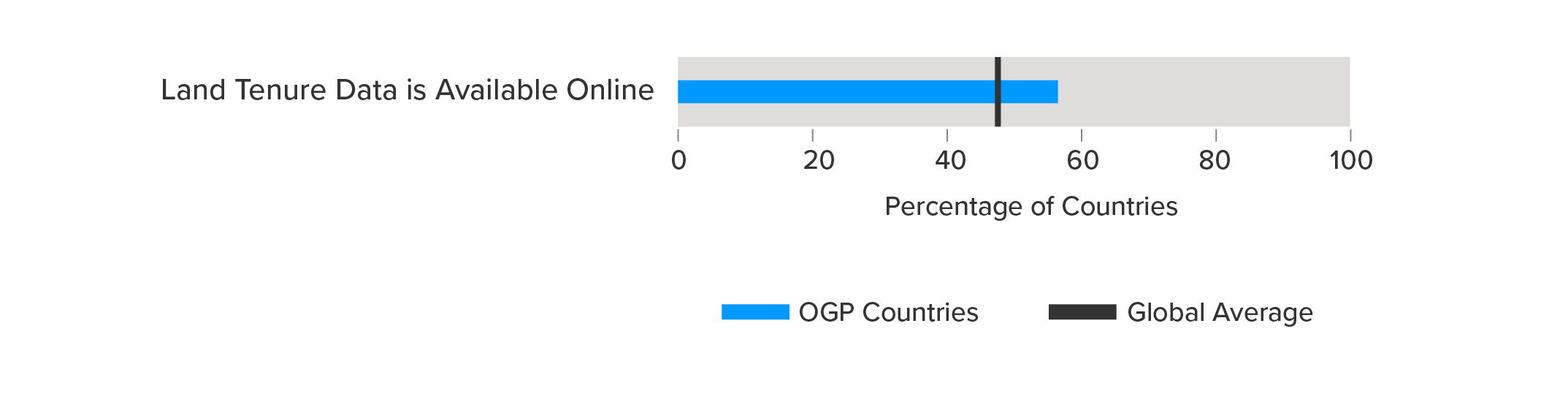

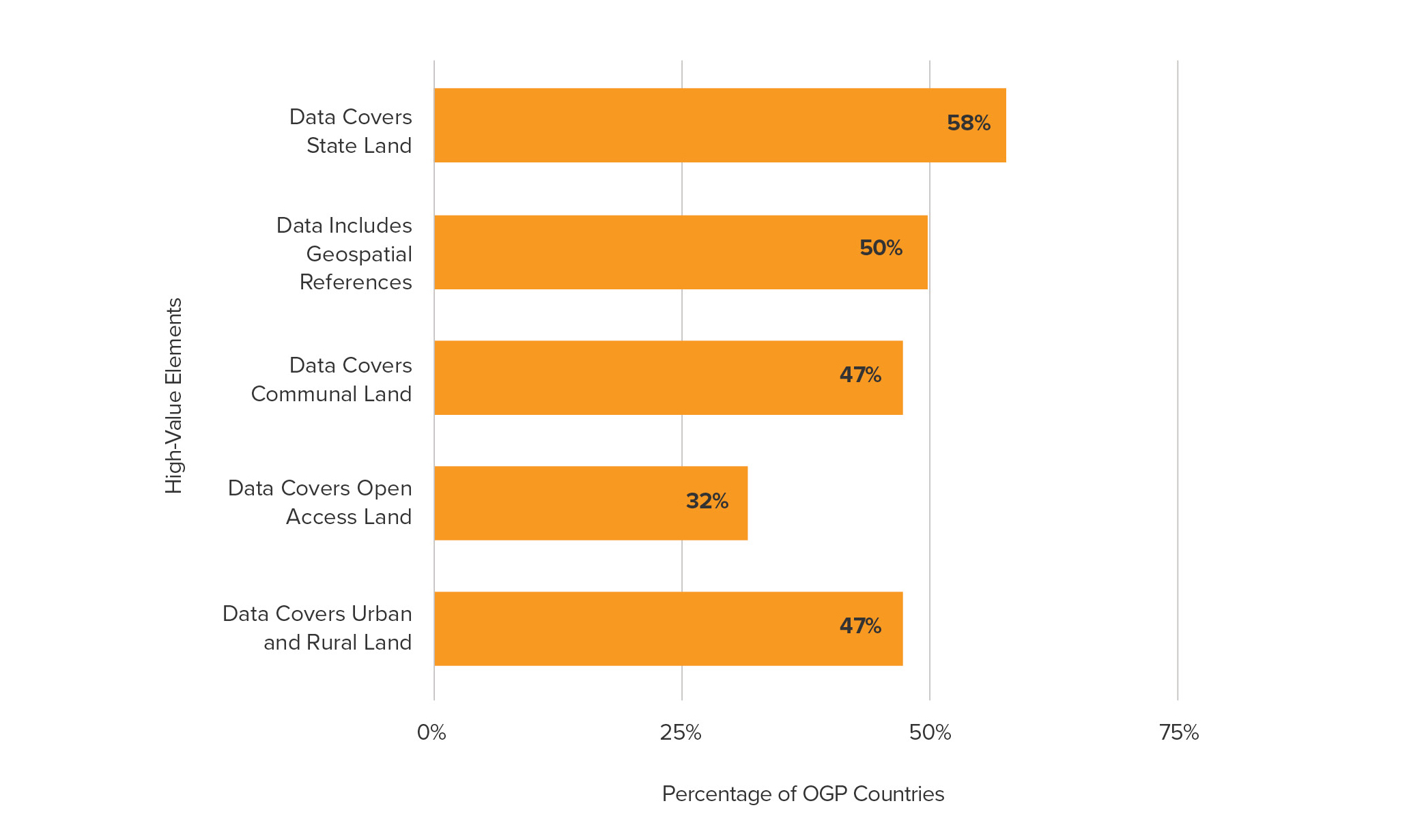

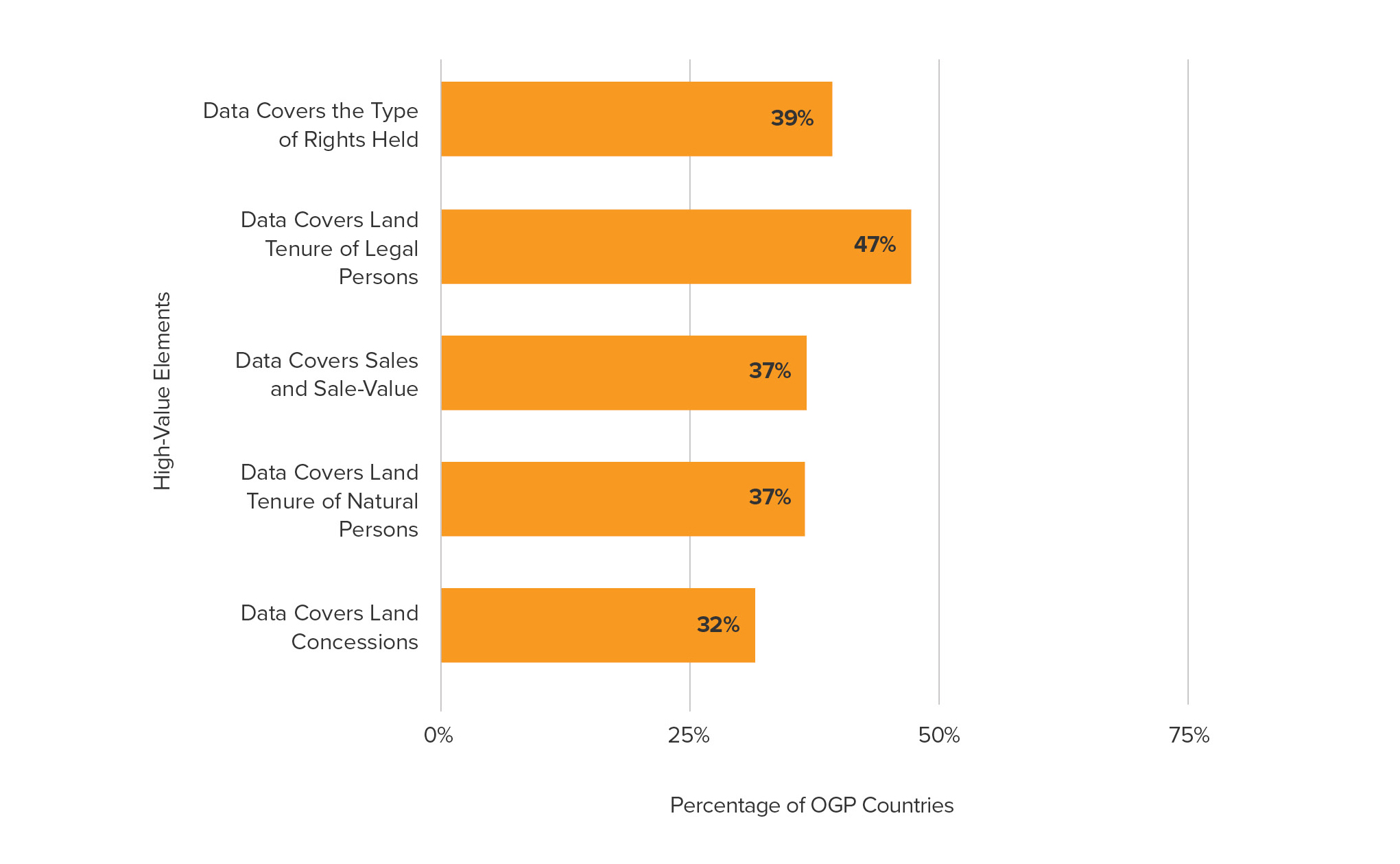

Land Ownership and Tenure | About half of datasets cover different types of land tenure. Only one-third include information about beneficiaries of land tenure and their rights. |

Public Procurement | Most datasets include contract descriptions, costs, and dates, but few countries publish data on contract implementation. |

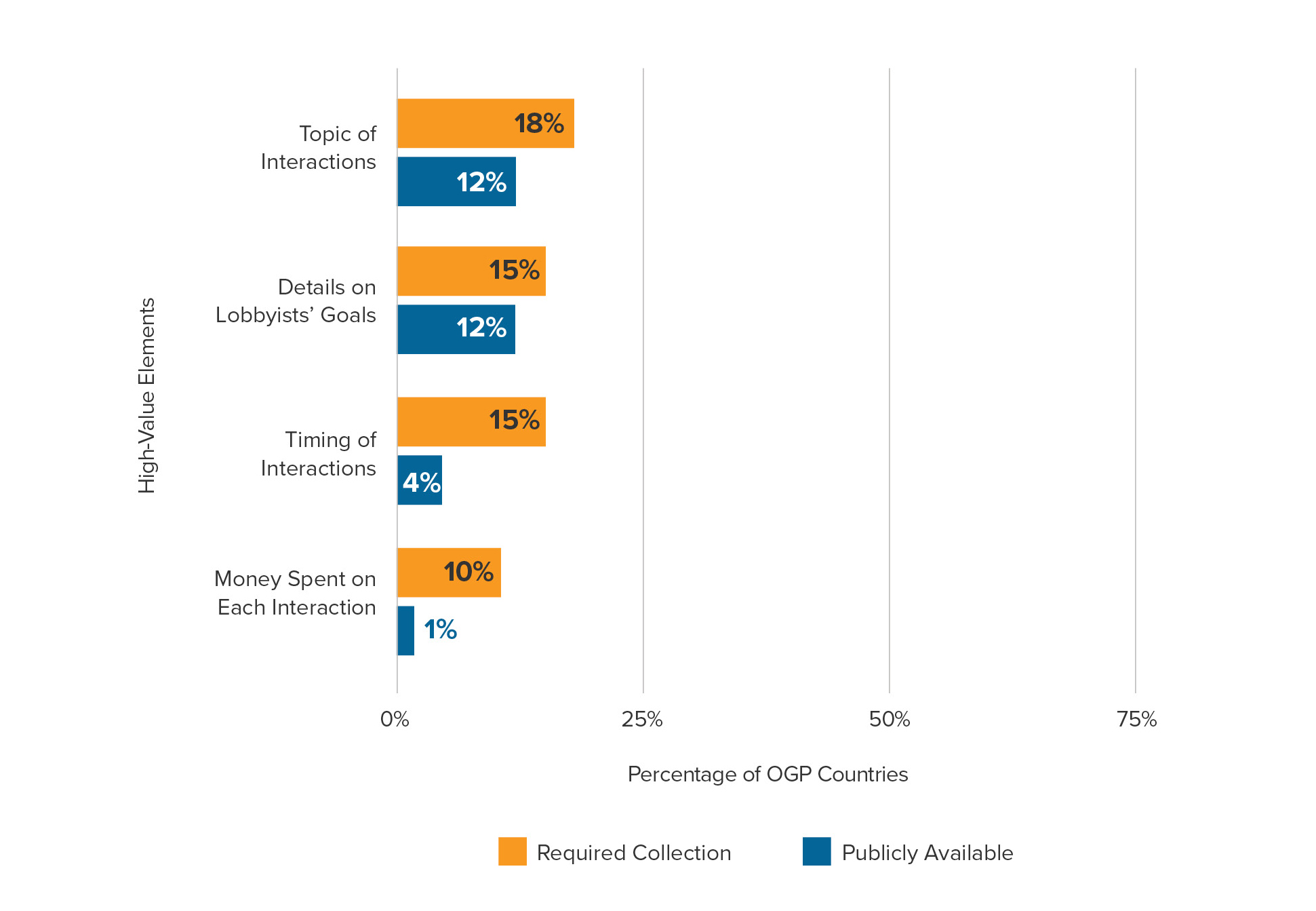

Lobbying | Half of available datasets include the topic and goals of interactions. Fewer than a quarter include dates or the amount of money spent. |

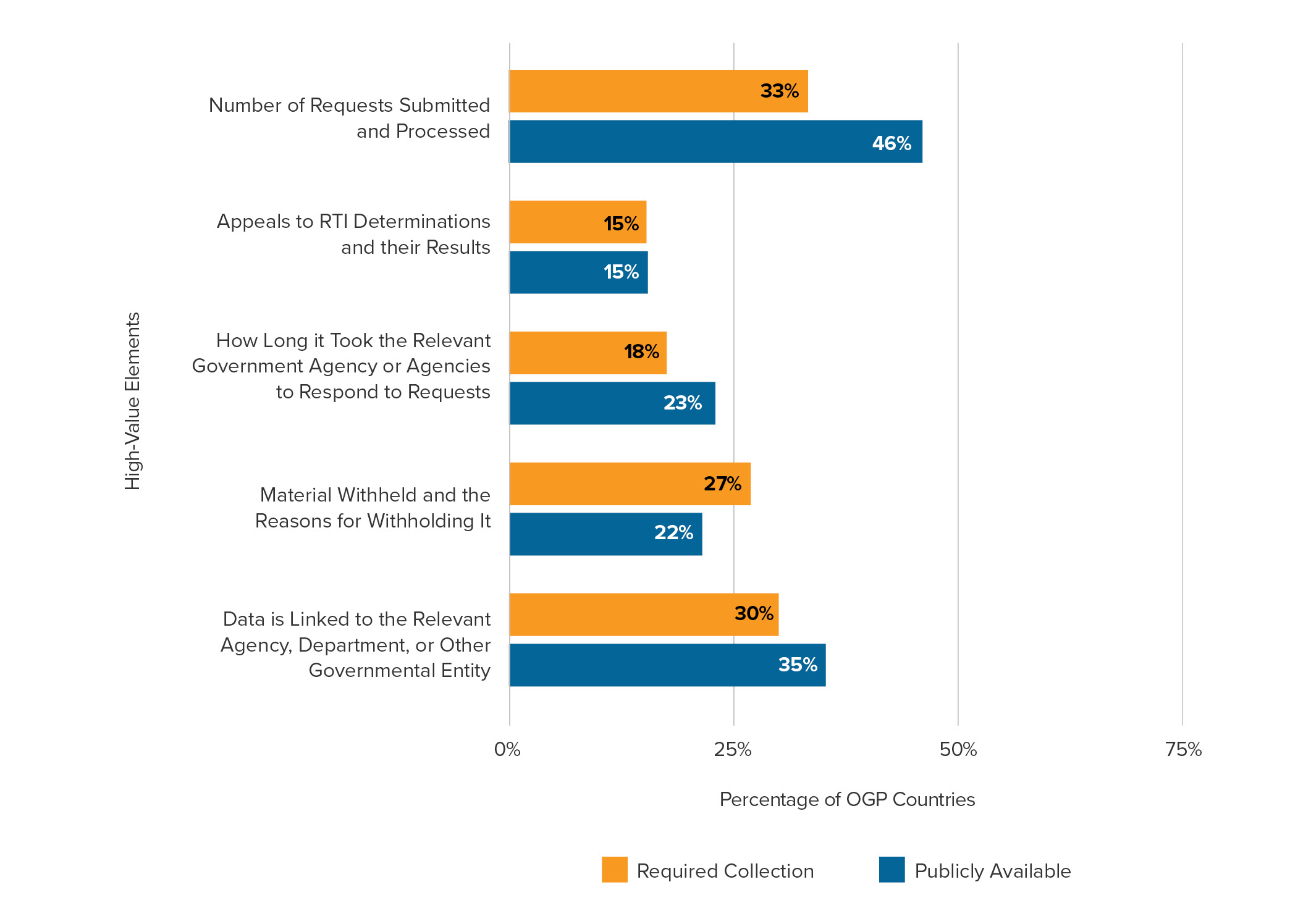

RTI Performance | Most datasets specify the number of requests submitted, but fewer than half cover delays, materials withheld and reasons for withholding, or appeals. |

Rulemaking | Fewer than half of datasets include proposed regulations, and fewer than a quarter cover final regulations, public comments, or supporting documentation. |

Interoperability | Most assessed OGP countries do not have common identifiers for the simple reason that they do not publish the relevant datasets. Where datasets are available, some employ useful common indicators, most frequently around companies. |

Data alone, however, is not enough to counter political corruption. Even data that includes high-value elements and is published online in reusable formats must be accompanied by other layers of accountability policies. For this reason, each policy area module in this report includes a Beyond Open Data section that outlines complementary steps needed to achieve impact. Among other reforms, these sections underscore the importance of citizen engagement and monitoring, robust regulatory environments, and independent oversight mechanisms for verification and enforcement.

Regional Findings

Innovating New Links

Just as the five global data gaps are found across all regions, so too are stories of innovative reforms. Each regional module in this report covers not only the state of open data against political corruption in the region, but also an overview of reforms advanced through the OGP platform and examples of regional innovations. These findings are summarized here:

- Africa and the Middle East: OGP members in the region are making some of the most ambitious commitments in OGP action plans, particularly around company beneficial ownership transparency and land ownership transparency. However, data publication remains an important challenge. Fewer than one-quarter of countries in the region publish data related to each policy area, with the exception of public procurement. Ensuring that legal frameworks mandate both data collection and publication is an important avenue for future reforms.

- Americas: The median OGP country in the Americas publishes data for most of the policy areas reviewed. Challenges include improving the usability of data and publishing high-value information like common identifiers that enable linking datasets. Nearly every OGP country in the region has advanced procurement reforms through OGP—with many achieving significant results. More commitments are needed in other areas, like beneficial ownership transparency and asset disclosure.

- Asia and the Pacific: Many countries in the region lack publicly available data for multiple policy areas, particularly beneficial ownership and lobbying. OGP members are making commitments in their OGP action plans to address these challenges, but translating them into results through effective implementation has been difficult, especially around procurement and asset disclosure. Examples of regional innovations in these areas show the way forward.

- Europe: European countries publish data in some form across most of the policy areas reviewed. Areas for improvement include publishing more high-value information, publishing data in usable formats, and making datasets interoperable through common identifiers. Several OGP commitments from the region have achieved transformative results, but more commitments are needed; with the exception of procurement, each policy area remains unaddressed in OGP by over half countries in the region.

Country Findings

Areas for Action

Although political corruption is a global problem that requires solutions across borders, implementation of reforms begins at the domestic level. Therefore, this report includes a Data Exporer that helps readers visualize the state of open data against political corruption in each country. This online tool enables reformers to compare themselves to other countries, identify actionable areas for improvement, and find specific datasets that can be improved.

Like the rest of the report, the Data Explorer emphasizes learning from the experiences of others. Specifically, it spotlights examples of promising initiatives to inspire the adaptation and adoption of high-impact reforms around the world. These spotlights mirror the longer-form Lessons from Reformers included throughout the report and showcase the diversity of efforts that countries are undertaking to counter political corruption (see Table 4).

Table 4. Lessons from reformers come from every corner of the world

Policy area | Lessons from Reformers |

Asset Disclosure | Georgia has implemented an independent monitoring system for public officials’ asset declarations. |

Paraguayan civil society launched an online portal during the pandemic that enables citizens to flag government data irregularities to auditors. | |

Ukraine has had a long journey of mandating, publishing, and prosecuting violations of asset disclosure data. | |

Political Finance | Croatian civil society developed a database that enables searching and comparing donors, campaign expenses, media discounts, and social media expenses. |

Panama, as part of its OGP action plan, created a public, user-friendly database to monitor the funding of political parties by the electoral authority. | |

Company Beneficial Ownership | Kenya, as part of its OGP action plan, passed a law requiring companies to keep a register of its members, including beneficial owners. |

Armenia amended existing legislation to require that beneficial ownership information be included in a public register. | |

Portugal implemented its public beneficial ownership register in 2019, and by January 2021, nearly half a million companies had registered their beneficial owners. | |

Ghana implemented an electronic beneficial ownership register in 2019 and is using its OGP action plan to improve the quality and accessibility of the data. | |

Land Ownership and Tenure | Liberia has improved the openness of land management through recent OGP action plans, including by making land information and data publicly available. |

Uruguay has improved the openness of its cadastre through its OGP action plans, such as by improving citizen engagement through an online portal. | |

Public Procurement | Finland, as part of its OGP action plan, published procurement data through an open access service that emphasizes accessibility and usability for citizens. |

Colombia is implementing open contracting reforms that improve competition and increase suppliers in the public procurement market. | |

Lobbying | Chile enacted legislation in 2014 to modernize its system of lobbying and used its second OGP action plan to implement and monitor the legislation. |

Madrid, Spain, as part of its OGP action plan, created a mandatory lobby registry to ensure traceability of public decision-making, and as of early 2021, over 500 lobbyists have successfully registered. | |

Right to Information Performance | Nigeria is using its OGP action plan to improve RTI compliance by proactively disclosing information, establishing an electronic portal for information requests, and mandating annual reports on request and response rates. |

Uruguay used its OGP action plan to set up an online system to track requests for information and more recently committed to implementing a system to evaluate websites of reporting entities to improve the quality of information. | |

Rulemaking | The Slovak Republic, as part of its OGP action plan, created rules outlining public involvement in the development of selected policies. |

Sunlight Labs tools Scout and Docket Wrench are examples of innovative tools that can be built using open regulatory data. | |

Croatia, Kyrgyz Republic, Malta, Mexico, and Norway have used their OGP action plans to implement unified websites that enable the public to submit comments on regulations. Italy used its OGP action plan to reform impact assessments, ex-post evaluations, and stakeholder consultations during the rulemaking process. | |

Interoperability | Kenya’s opportunities to standardize procurement data and track beneficial owners provide lessons for addressing policy and technical aspects of interoperability. |

The United States, as part of its 2013 OGP action plan, committed to moving toward a more interoperable and public data system. By 2022, the US government has implemented a single, publicly owned, nonproprietary common identifier for all contracting companies. |

Moving Forward

Broken Links is about more than data. It is about countries challenging one another to improve. This requires advocates and reformers inside and outside of government to continue to push to release data, reform institutions, and forge relationships that can help stem corruption. This can be supported through commitments in OGP action plans and in other international fora along with other reformers from around the world. It cannot, however, work in isolation. The links in the chain of accountability that are broken, have gone missing, or have never existed will need the cooperation of many—across borders, across parts and levels of government, across parts of society—to be mended and put into action.

GLOBAL OVERVIEW

As the report you are reading is being completed (mid-2022), the European Commission has closed its case against the Czech Republic, finding it liable for misallocating millions of euros in subsidies. Now, former Czech Prime Minister Andrej Babiš is currently facing charges of fraud in his country for pocketing millions of euros in EU agricultural subsidies. This marks another high-profile case of potential political corruption and abuse of power—reaffirming the importance of transparency to hold elected officials accountable (see Following the Money: The Case of Andrej Babiš).

More specifically, the Babiš case points to the need for data about elected officials—accessible, public data about what they own and with whom they may be working. It also highlights the active role of civil society organizations and watchdogs in tracking money across borders, which is only possible when the data itself is open across borders.

The Babiš case is not unique and is indicative of a troubling corruption at the top of many political systems. Powerful politicians and influencers who commit crimes often use international financial tools to enrich themselves, then pour that money back into their campaigns to tip elections in their favor.

The solution to political corruption must focus on improving political systems. Democratic politics may be messy and contentious, but they need clear, transparent rules and strong standards for compliance with the law. People need to know who their governments listen to when making laws and policies, who pays for political campaigns, and who benefits from political decisions. Publicly available open data is an essential part of this.

Additionally, solutions require more than one dataset. Multiple interoperable datasets can help identify suspicious activity. The Babiš case included beneficial ownership of companies, land registries, subsidies data, and public contracts.

Data alone is not enough to combat corruption. Paired with strong enforcement institutions and active civil society organizations, this data helps the world to stand a better chance of turning back the wave of autocratization and the growing sense of grand corruption.

That is what this report, Broken Links: Open Data to Advance Accountability and Combat Corruption, is about. The title, “Broken Links,” refers to missing data essential to understanding how politics works in each system. The subtitle reflects the focus of the report—open data— while acknowledging that it is one tool of many necessary to fix the problem.

Over three years in the making, the report examines the use of data systems to protect democracies from corruption and undue influence—or, more specifically, how these data systems are (or are not) built to address corruption. And it builds on research by experts worldwide, led by the Global Data Barometer team at the Latin America Open Data Institute.

The report goes beyond an assessment of the state of play, however. By showcasing promising reforms, offering practical recommendations, and identifying guidance for effective implementation, it can also help reformers close existing gaps. Concretely, the report aims to be a tool for countries to compare themselves with one another, share lessons learned, and adapt high-impact reforms to their contexts. In that sense, the report serves not only as a benchmark as to where anti-corruption data stands in the third decade of the millennium, but as a resource for where it could go in the next.

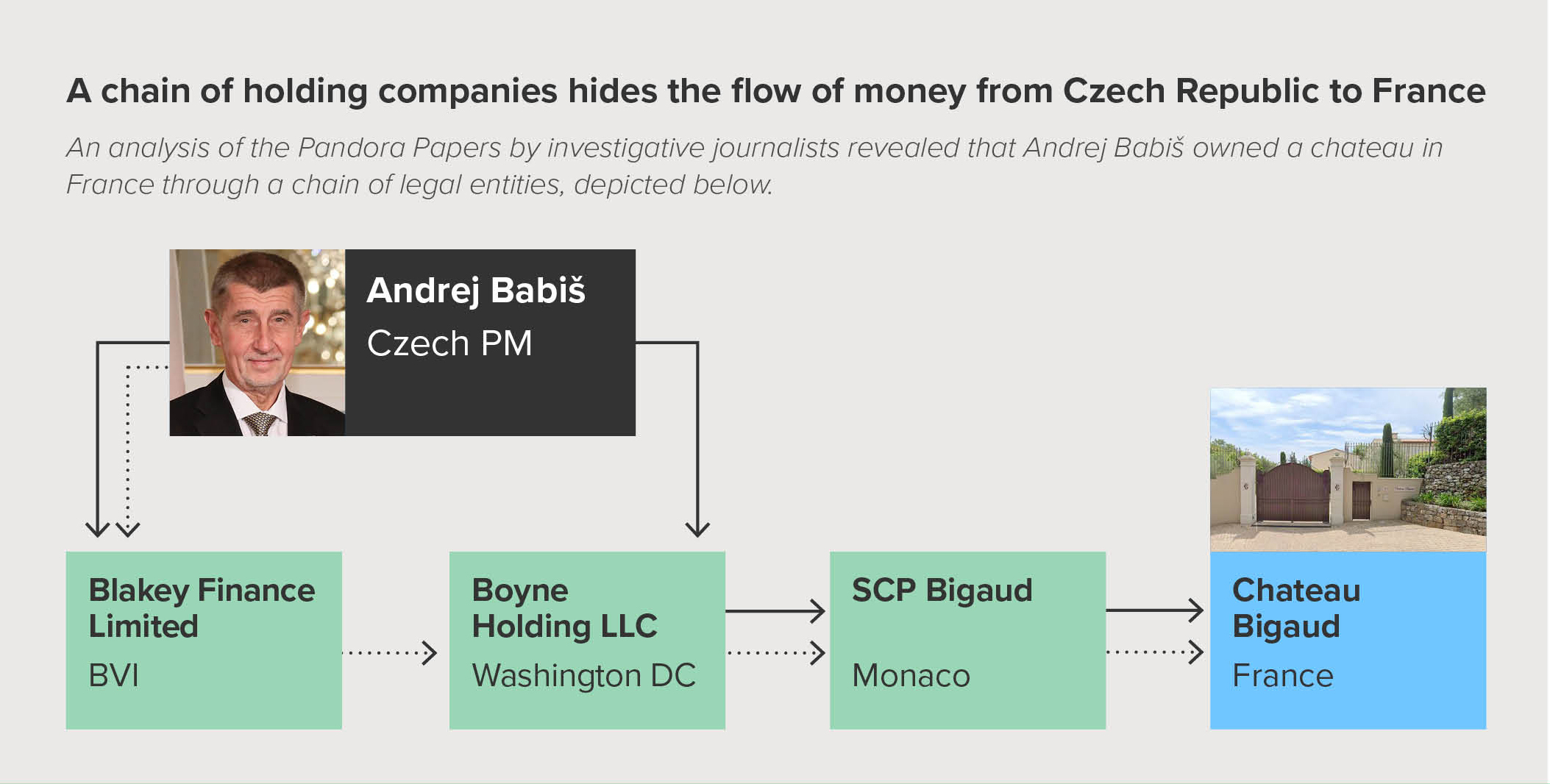

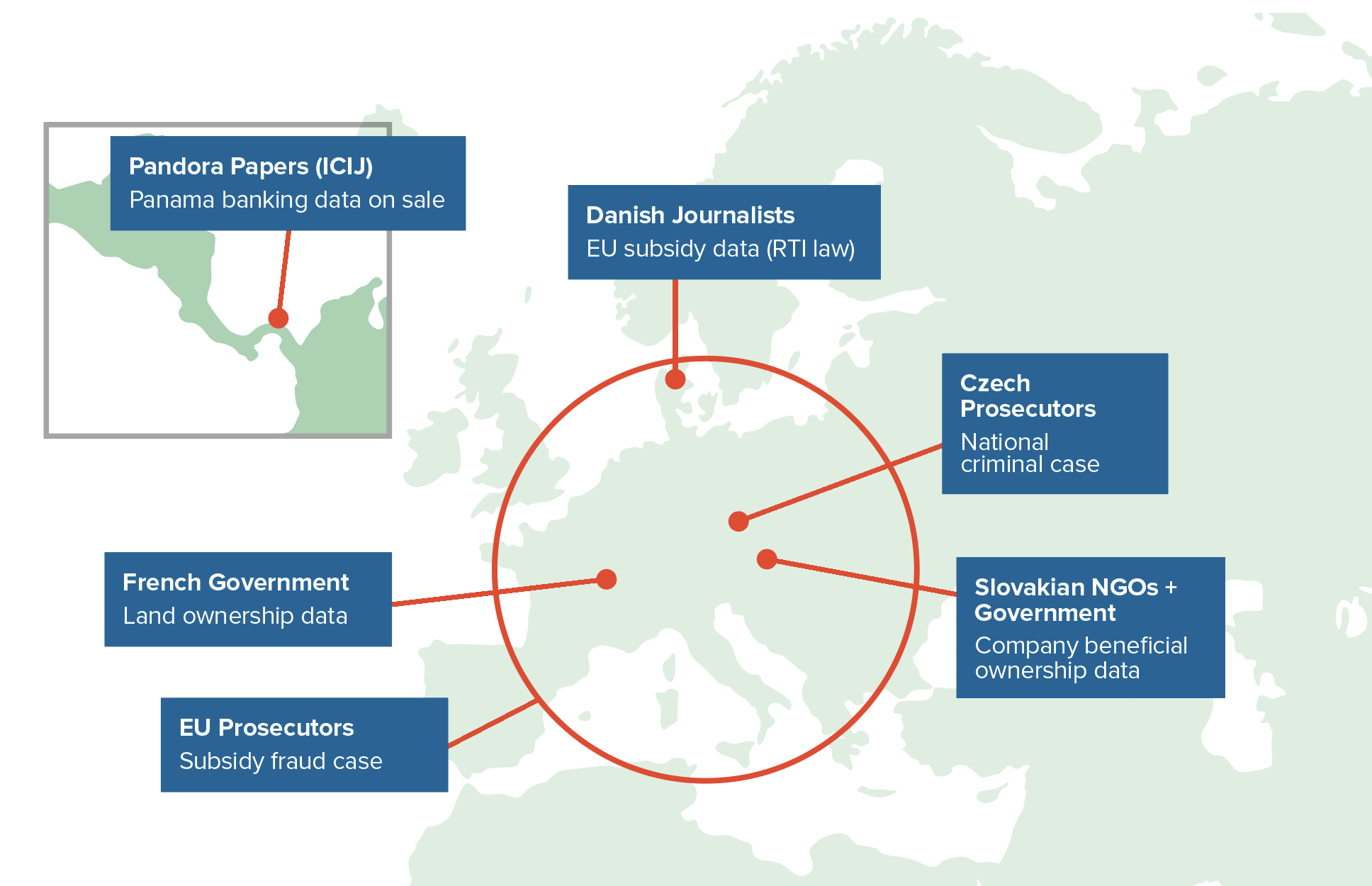

Following the Money: The Case of Andrej Babiš Former Czech Prime Minister Andrej Babiš is currently facing charges of fraud in his country for pocketing millions of euros in EU agricultural subsidies. At the time of publication, the European Commission has closed its case and deducted fraudulently obtained funds from Czech EU funds. The case now moves to the national level. The Czech case shows how corruption is international in nature, and its solution is too. Detecting and acting on that corruption requires accountability institutions—watchdogs inside and outside government, whistleblowers, and journalists—working across borders to bring together diverse data. Throughout this report, successful cases of cleaning up corruption show the power of collaboration and interconnected data. The Czech media first reported that former Prime Minister Babiš had separated his personal farm from his larger agribusiness conglomerate, Agrofert, making the farm eligible for €2M worth of EU subsidies. After receiving the subsidies, the farm was reabsorbed into the larger conglomerate. According to the New York Times, as the sole beneficiary of two trust funds that owned 100 percent of the shares of Agrofert, Babiš received at least US$42 million in agricultural subsidies from the EU, which was ruled a clear conflict of interest by the European Commission. The European Union has already fined Czechia €3.3M for mishandling the funds, and the country awaits to see if the courts will find the former prime minister guilty of fraud, charges he has denied. The Pandora Papers further revealed that an additional €13M had been moved through offshore holding companies and law firms to enable Babiš to buy a chateau in the South of France (see Figure 1). Setting up these kinds of offshore companies does not violate any domestic laws. However, it does raise questions about the source of the wealth and why Babiš sought to hide it. These questions are particularly concerning given his role as a politician tasked with safeguarding the public trust. This investigation was the product of collaboration between not-for-profit organizations, journalists, and other public officials. For example, the Transparency International chapter in Czechia used Slovakia’s public register of beneficial owners of companies to discover the controlling share that Babiš had of Agrofert. The New York Times also carried out an investigation, which produced a front-page news story on the recipients of EU subsidies. In addition, the publication of banking data by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, through the Pandora Papers, showed exactly how Babiš moved money through holding companies. Figure 1. A chain of holding companies hides the flow of money from Czech Republic to France An analysis of the Pandora Papers by investigative journalists revealed that Andrej Babiš owned a chateau in France through a chain of legal entities, depicted below.

Figure 2. A chain of data and accountability actors discovered evidence of misused funds

|

Why Focus on Anti-Corruption?

Being able to observe, inform, and influence powerful decision makers is widely recognized as a fundamental right and a part of modern citizenship. Enshrined in the national laws of most countries and a large body of international and human rights law, the history of the last several centuries has revolved around extending political rights to larger and larger segments of society.

In the more democratic parts of the world, this right and ability to take part in governing comes with an added expectation. Each person should have both equality and equal representation before the law. Yet, in most of the world, not only does this ideal remain unrealized, it is also increasingly under direct assault.

This assault is two-pronged. First, it is spearheaded by growing illiberalism in many countries, with foreign and domestic proponents. These forces advocate for alternatives to dialogue, tolerance, and nonviolence that are the hallmark of the global democratic progress of the last century. Second, the assault is sustained by a model of “kleptocracy,” where shared public resources—money, clean environments, and safety—are redirected to enable the powerful and connected to undermine any practical public accountability.

Unfortunately, this is not the first time the world has faced a wave of corruption and authoritarianism operating hand in hand—whether in the 1960s or the 1930s. Yet, fortunately, past experiences also illuminate the road to renewal. These experiences show that democratic practices can be renewed and access to decision-making can be restored.

This report focuses on limiting the undisclosed, the unchecked, and the undue. It does this with a focus on the antidotes to secrecy and exclusivity—transparency, participation, accountability, and inclusion. These are values central to the Open Government Partnership. Moreover, this report looks at how data and the institutions that collect, publish, analyze, and act on it can help improve government for everyone.

Why Now?

This report grows out of a large focus of OGP: reducing corruption and improving democracy. This has been at the core of the partnership’s mission since its founding in 2011 and has ushered in key victories. These have included the growing wave of beneficial ownership transparency (BOT) reforms worldwide and the rise of open contracting as a global norm for public procurement practices. In fact, it was at the London OGP Summit, in 2013, when the UK announced the world’s first global company BOT register.

Democratic freedoms and civic space, too, have been central to OGP. The right to seek information, an express and universally recognized element of free expression, is a core value of OGP, and members are expected to enact legislation to protect and promote this right. In recent years, OGP has increasingly focused on democratic freedoms, civic space, or civil liberties as instrumental to—and an essential goal of—open government. The evidence has also accumulated that these rights, which are valuable in and of themselves, also support better human and economic development.

Yet, as the 2021 report, OGP at Ten: Toward Democratic Renewal, showed, the rhetoric has not always matched the action. OGP action plans have often been at the forefront of democratic innovation—especially in the fields of right to information (RTI) and public participation. However, on the whole, analysis shows that most plans remain silent on reinforcing democratic fundamentals—strengthening elections, enhancing the quality of representation, and protecting the rights to free expression, assembly, and association.

This report focuses on what can be done to address the gap in anti-corruption data and its use. The solutions herein may not by themselves solve the challenges of the moment, but they can begin to answer: “What next?”

A Data-Focused Approach

This report focuses on using data as a tool to combat corruption and make political systems work for more and more citizens. It is the result of years-long collaboration between civil society organizations, multilateral organizations, and governments around the world.

The Global Data Barometer (GDB), a collaborative study across 109 countries, led by the Latin American Open Data Initiative (ILDA by its Spanish acronym), examines the state of data as it relates to pressing societal issues, including control of corruption. Specifically, the GDB is an expert survey, drawing on primary and secondary data, that assesses data availability, governance, capability, and use in more than 100 countries, 67 of which participate in OGP (see A Short Summary of the Global Data Barometer, or refer to About Broken Links, for details). This work is the result of collaboration across multiple organizations, including OGP, Transparency International, Land Portal Trust, Open Ownership, Open Contracting Partnership, the Global Initiative for Fiscal Transparency, and regional hubs.

This report looks at a variety of anti-corruption datasets that should be made public writ large, which includes the “Political Integrity” module of the GDB (the largest of the survey), among others.[1] This report necessarily does not include all aspects of political corruption, including many important ones. Instead, it focuses on areas that are strategic priorities of OGP[2] and are most amenable to analysis through the lens of open data, which is the focus of the GDB.[3] Altogether, the report looks at the following nine policy areas:

- Asset disclosure: Basic data on elected officials and senior appointed officials and associates, including their assets, liabilities, and finance before, during, and after office, can better inform the public of potential conflicts of interest, illicit enrichment, or compromising liabilities. Disclosure of data on politically exposed persons extends to family members and allows for cross-national comparison.

- Political finance: Knowing who gave to campaigns, politicians, and parties is essential to ensure that officials serve voters and not the highest bidders. Knowing that campaigns spend that money on legitimate expenses also ensures that everyone follows the same rules. Additionally, it can shed light on corporations’ ideological and political stances, so consumers make informed decisions.

- Company beneficial ownership: Anonymous companies are the most popular legal vehicles to move ill-gotten gains from corruption, to aggressively avoid taxation, and to commit contract fraud (by bidding multiple times from one company or evading blacklisting). In the context of political corruption, politicians may use anonymous companies to hide money, and donors may use them to hide donations, bribes, or kickbacks.

- Land ownership and tenure: Knowing who owns the land and under what system of land tenure is essential, as land is one of the major targets of corrupt acts (including through eminent domain practices) as well as targets for money laundering of ill-gotten gains from corruption. In the context of political corruption, politicians may choose policies that are favorable to particular individual landholders or direct subsidies or expenditures to particular landholders.

- Public procurement: Public procurement is the largest single vector for waste, fraud, and abuse. This report is the first global report to examine how many countries publish centralized open data on nationally awarded contracts. This allows everyone to see whether procurement opportunities have been adequately advertised and are genuinely competitive, reducing the opportunity for waste, fraud, and corruption. In the context of political corruption, open contracting data allows the public to see whether politicians are abusing public resources—illicitly rewarding themselves, supporters, and family members, and/or seeking award kickbacks.

- Lobbying: In a democracy, everyone should have the right to tell their lawmakers what they think. But, often, those interest groups with more resources get to influence policy-making more effectively. Knowing who influences the law, who they represent, and how much they spend is fundamental to shaping advocacy strategy and determining how constituents should engage leaders.

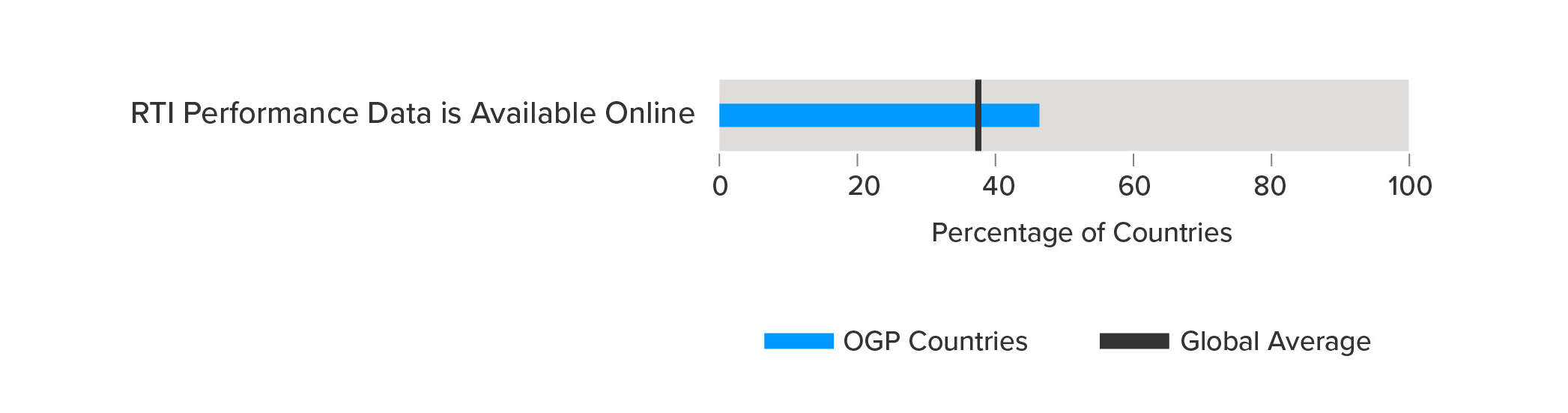

- Right to information performance: Right to information (RTI) laws give the public insight into how government decisions are made and implemented. Most OGP countries have right to information laws. Almost all of those laws require agencies to publish information on how they are being executed. This report is the first global report examining whether governments are publishing performance data on right to information, an essential step to effective implementation.

- Rulemaking: In most modern countries, parliaments delegate the formation of regulations to ministries, departments, and agencies. Just as with lobbying data, the public and watchdog organizations need to know how to take part in the formation of regulations, who participates, how it influences the outcome, and whether those regulations were subject to challenge.

- Interoperability: Linking datasets is essential to understand, identify, and prosecute corruption. It requires bringing people and organizations together but also creating systems of common identifiers (such as companies, pieces of legislation, or politicians), which allows the public to participate in governance and monitor undue influence.

A Short Summary of the Global Data Barometer The Global Data Barometer (GDB) is a collaborative study that measures the state of data in relation to urgent societal issues. Its development began in 2019 in response to the needs expressed at the 2019 OGP Global Summit in Canada for updated, in-depth, country-level insights on data. Together with regional hubs and thematic partners, the GDB is a global expert survey drawing on primary and secondary data that assesses data availability, governance, capability, and use around the world to help shape data infrastructures that limit risks and harms. The GDB launched in May 2022. It covers May 2019 through May 2021 and includes 109 countries, 39 primary indicators, and over 500 sub-questions, for a total of more than 60,000 data points. It addresses the following areas: climate action, company information, health and COVID-19, land, political integrity, public finance, and public procurement. For more details on survey design, data collection, and specific indicators, see the About the Data section of this report. |

Limitations

Given the scale and complexity of the data in question, this report must maintain clear areas of focus. This presents the following limitations:[4]

- Policy area coverage: The report cannot cover every angle of political corruption, especially those that do not (yet) have a straightforward data-centric treatment. This means that important issues in cleaning up politics, such as the use of state resources for campaigning or ethics revolving door policies, are not included.[5] This data-centric approach could be expanded in the future with more topics and a wider focus on remedies.

- Open data focus: This report builds off the work of the Data for Development Network (D4D). Consequently, it focuses on transparency generally, and data mandates and use in particular. OGP values and mission go well beyond data—from strengthening right to information and deliberative democracy to access to justice and more inclusive decision-making. It is widely recognized that, in order for data to have an impact, it must be used by accountability institutions and supported by democratic practices. However, improving data remains an important starting point in combating corruption and an area where the evidence in this report shows just how much needs to be done. For those interested in reforms beyond data, a selection of resources is available in the box, Additional OGP Resources on Political Corruption.

- Policy and practice focus: As OGP is best placed as an organization that supports policy adoption and implementation, this report emphasizes policy and basic practice rather than technical details. For those interested in technical implementation, the OGP Support Unit can make introductions to organizations that can provide more support.

- Country coverage: This report is an OGP resource and therefore focuses on OGP countries. While there are inspiring examples, useful data, and work to do beyond the Partnership, this report primarily aims to support reforms through OGP and related processes. However, at the time of publication, ten national OGP members are not covered due to inability to find researchers.[6] The authors and collaborators are currently seeking a solution.

- National-level policy: This report focuses on national-level data from the GDB. Many, if not most, OGP countries have some federal or decentralized structures with regard to the policies covered in this report. For example, the majority of procurement may actually take place at subnational levels. This report, for practicality’s sake, cannot cover all of the nuance and wealth of information at those levels. Readers curious about replicating this approach should feel free to reach out to the authors at: [email protected].

The staff of the OGP Support Unit hopes this report is an effective tool for campaigners and reformers inside and outside of government. While it details the many remaining challenges, it also shows clear pathways for progress. The challenges in OGP member countries will continue to evolve, but the collective charge of the Partnership over the next decade is clear: to protect democracy, one must fight corruption, and to fight corruption, one must strengthen democracy.

Additional OGP Resources on Political Corruption Making politics cleaner and more fair requires more than open data. While this report is focused on open data, it is part of a larger pool of resources that represent the innovations and experience of the global network. A number of highlights from the library of resources may be of interest to reformers, especially those wanting to go beyond open data:

Readers will find additional resources that are not directly produced by OGP but are excellent guides in the Guidance and Standards section of each individual policy area chapter. |

GOOD TO KNOW What Is Open Data? Publishing data openly is essential to ensuring that key anti-corruption datasets are interoperable, meaning they can be linked to each other. Interoperability increases the ability of government oversight institutions, civil society, journalists, and interested citizens to monitor and flag potential cases of corruption or fraud. But what exactly is open data? Open Definition Many organizations have their own shorter definitions of open data, but most adhere to the Open Knowledge Foundation’s Open Definition for a full, technical definition of what open data entails. A one-sentence version of the Open Definition is that “open data and content can be freely used, modified, and shared by anyone for any purpose.” The full definition continues to evolve based on conversations carried out openly. The Open Data Handbook, also published by the Open Knowledge Foundation, summarizes the full Open Definition into three main parts:

How the Term “Open Data” Is Used in This Report The GDB assesses countries on five key elements of open data for each indicator. For purposes of this report, a country meets the requirements for publishing open data in a specific policy area if the government-published data meets each of these five elements:

This report refers to these elements as “usability” features. In addition, this report takes into account elements of data quality that go beyond openness. These include high-value elements, comprehensiveness, and validation. |

Global Overview: Promising Starts, But a Long Road to Travel

In its most simple terms, this report shows that very few countries actually publish the most important data to counter political corruption. Although OGP countries publish data at higher rates than the rest of the world, they still face significant challenges, ranging from data that doesn’t cover the most valuable information to data that just doesn’t exist.

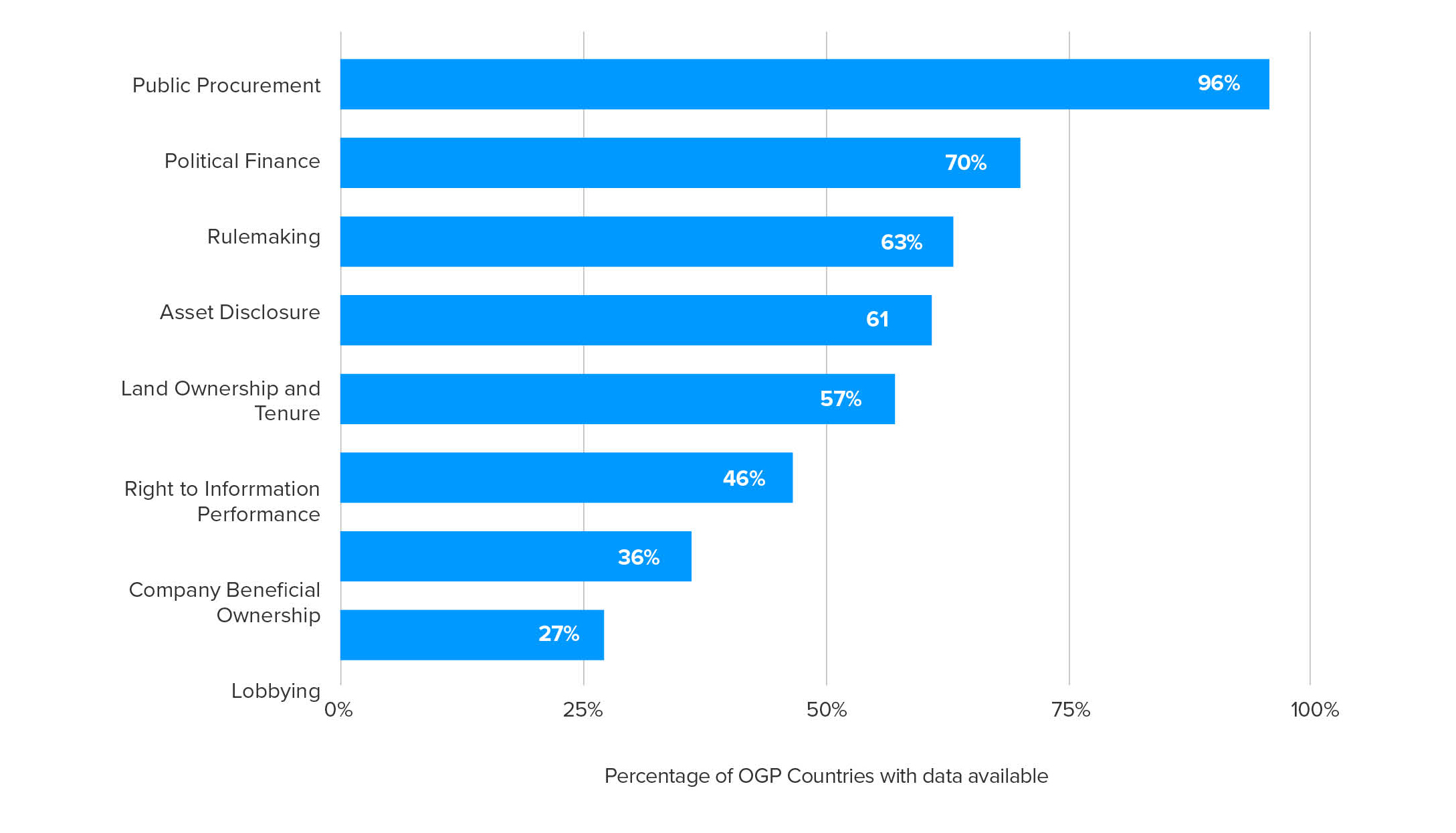

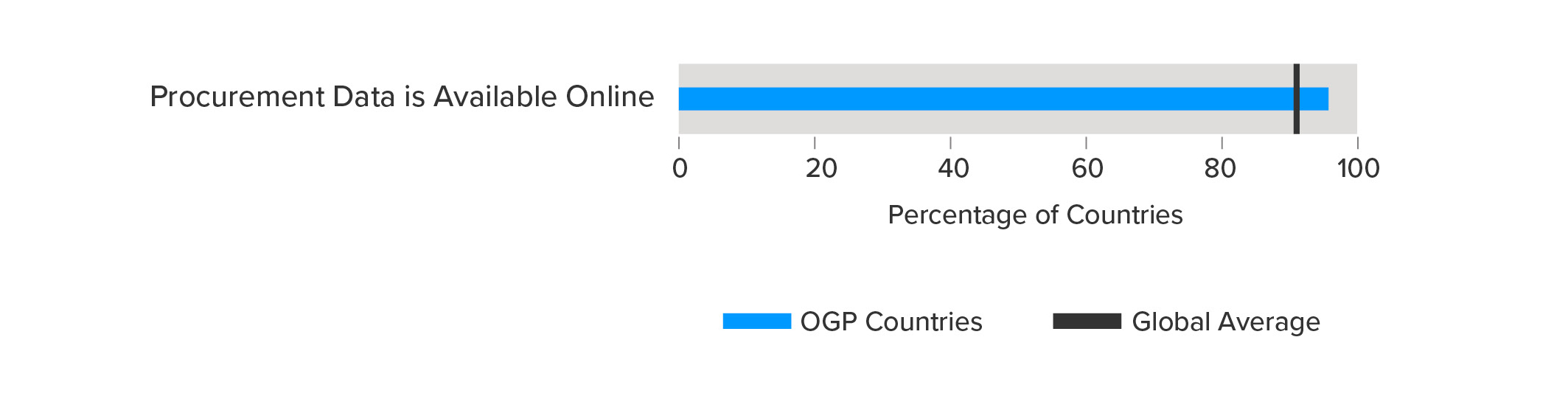

These reasons vary depending on the policy area, often quite significantly. For example, Figure 3 shows that nearly all OGP countries publish public procurement data online in some form, while fewer than a third publish lobbying data.

Figure 3: Data availability varies by policy area

This figure shows the percentage of OGP countries that publish data online. The sample includes all 67 OGP countries assessed by the GDB.

Note: This analysis only considers data that is available as a result of government action. See the About Broken Links section for details.

Data publication, however, is only part of the story. The strength of legal frameworks governing the collection of data, the type of information published, and the data formats used are all important factors.

The richness of the new GDB enables an analysis of these various factors, which provides a more nuanced understanding of the anti-corruption data landscape. In particular, the GDB data reveals several specific challenges that OGP countries face in collecting data, publishing it, and making it useful for accountability purposes.

Five Key Gaps

These global challenges can be summarized in the form of five key data gaps. These are gaps in collection, publication, high-value elements, usability, and use. Each gap is described below:

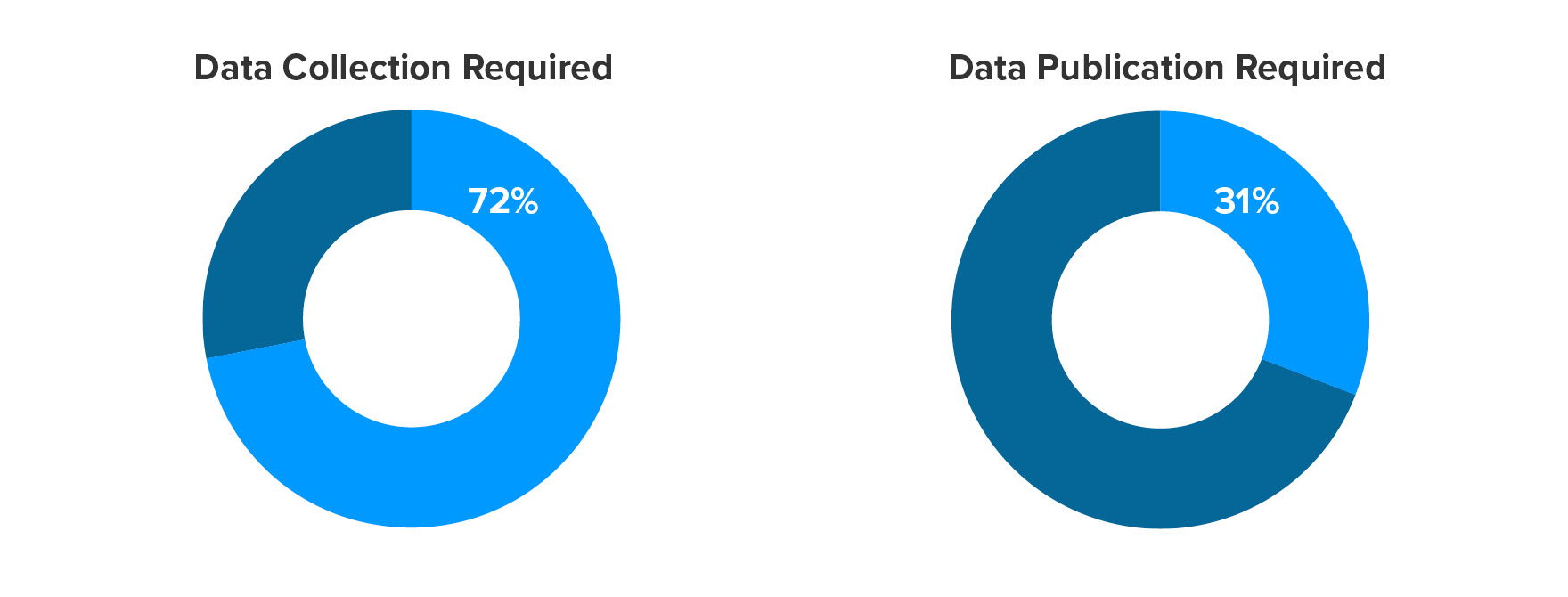

Collection Gaps

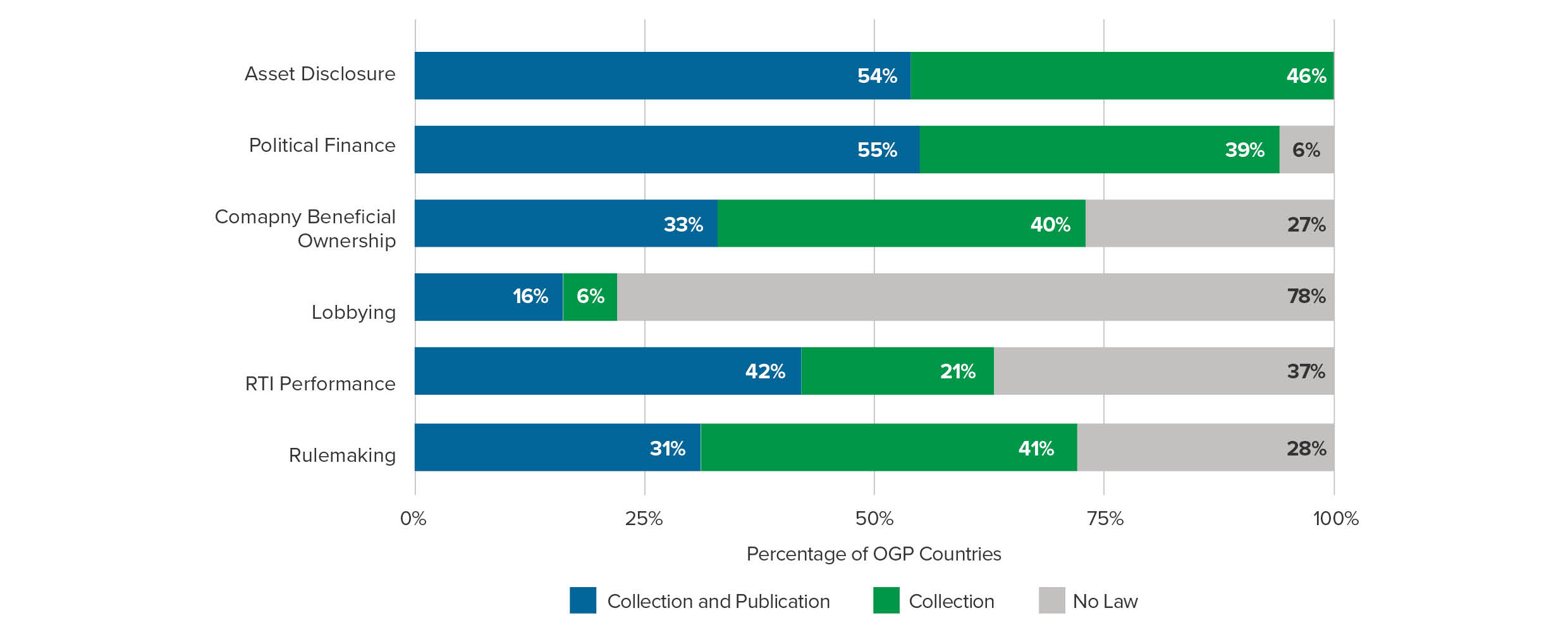

Many OGP countries do not have laws or regulations in place mandating the data collection. This is most notable in the area of lobbying, where fewer than a third of OGP countries require the collection of lobbying information (see Figure 4). Between one-quarter and one-third of OGP countries lack legal mandates for the collection of data on beneficial owners, rulemaking, and the performance of right to information systems.

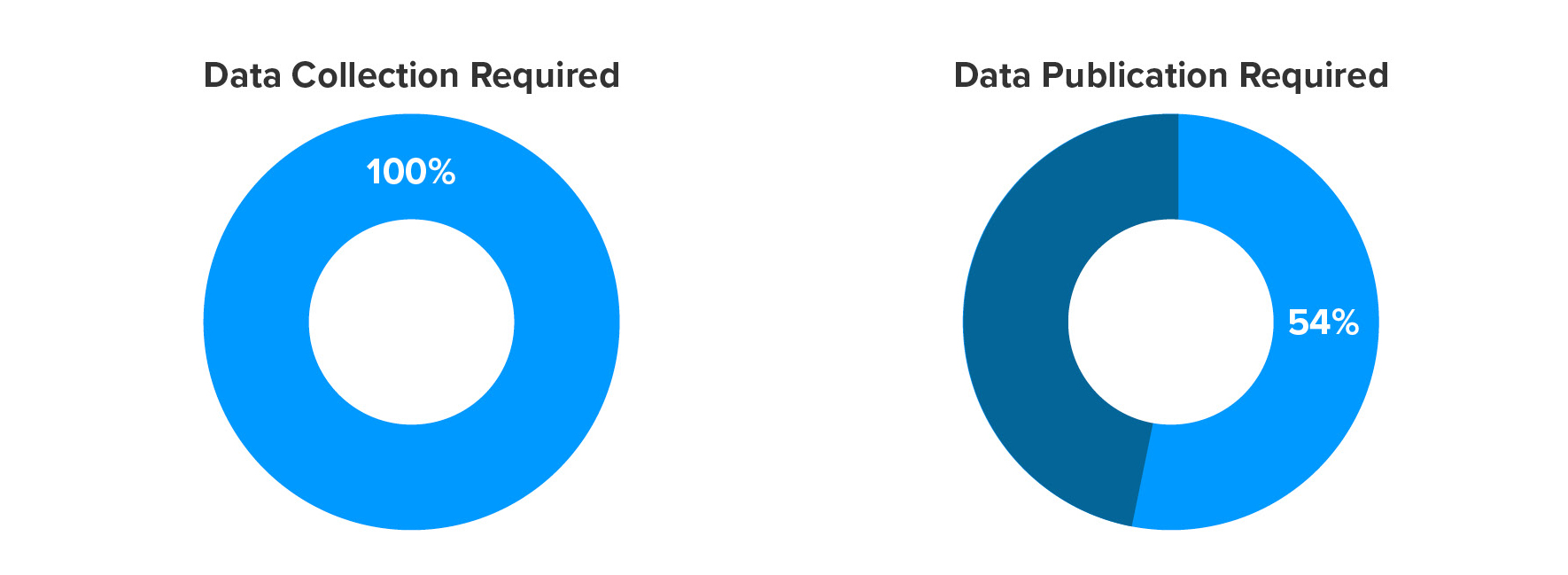

This collection gap exists even in policy areas where most countries have relevant legislation. For example, all OGP countries legally require public officials to submit asset declarations (this is one of the eligibility requirements for joining OGP). Yet, in a majority of these countries, government collection of data on assets of other politically exposed persons, like spouses and family members, is not required (see the Asset Disclosure policy area for details).

The same issue applies to other areas like political finance, where nearly all (96 percent) of OGP countries legally require political parties and campaigns to submit financial information. Only about half (55 percent) legally require the collection of donation timings and amounts, which are critical to understanding the influence of different actors in the political process (see the Political Finance policy area for details).

This all points to the urgent need for greater collection of anti-corruption data. In many cases, these are legal issues, specifically the absence of binding laws and policies that require data to be collected or the existence of weak legislation that does not require the collection of more granular, high-value data that can enable effective monitoring. For many OGP countries, this is a critical next step.

Figure 4. Law and policy requirements in OGP participating countries[7]

This figure shows the percentage of OGP countries with data collection and publication requirements across policy areas. The sample includes all 67 OGP countries assessed by the GDB.

Note: This analysis only considers binding laws and policies that exist and are operational. See the About Broken Links section for details.

Publication Gaps

Many countries do not publish essential data, even those that legally require its collection. On one end of the spectrum, nearly all OGP countries (96 percent) publish public procurement data online in some form. On the other hand, only about one in four OGP countries publish lobbying data, and one in three publish beneficial ownership data. Rates of data availability for the other policy areas fall somewhere in between. For most of these other areas, like asset disclosure and political finance, about one-third of OGP countries do not publish any data online.

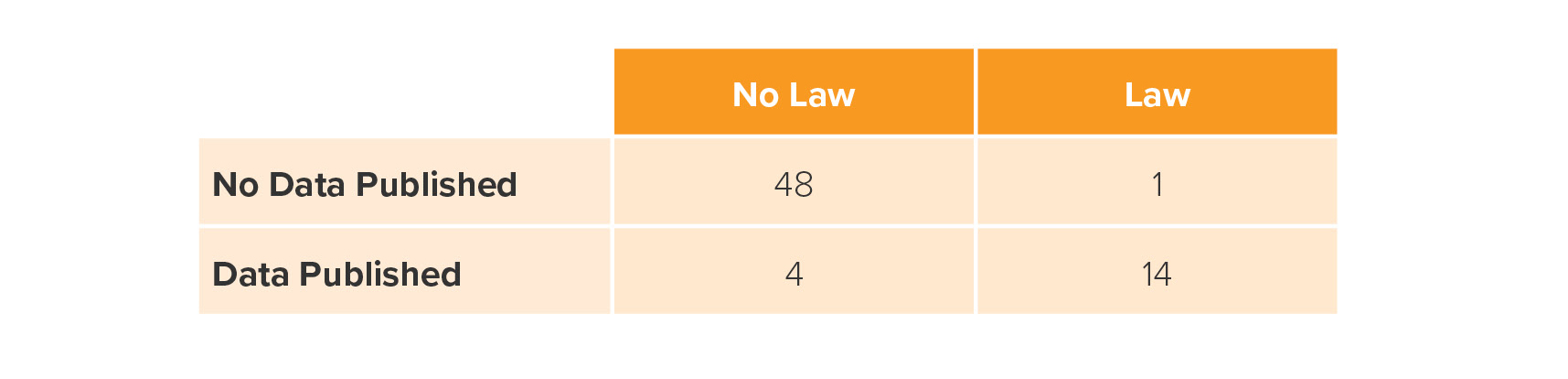

This is evidence of a significant gap between the number of countries requiring data collection and those actually publishing data (see Table 1). Nowhere is this gap wider than in asset declarations, where all OGP countries have a legal requirement that officials submit such information, but less than two-thirds actually publish any information online. Beneficial ownership data is another example; three-quarters of OGP countries require data collection, but only one-third publish any data online.

There are three possible drivers of these publication gaps:

- No legal framework: In some cases, OGP countries lack any sort of legal framework that requires collection—much less publication—of the specific data. Lobbying is a notable example, as mentioned in the previous section.

- Weak or unclear legal framework: In many cases, a legal framework requiring data collection exists, but it does not mandate publication. Beneficial ownership frameworks commonly fall into this category. As seen in Table 1, nearly three-quarters of OGP countries legally require the collection of beneficial ownership data, but only about one-third require the data to be published.

- Noncompliance with the legal framework: In other cases, legal mandates to publish data exist, but the data is still unavailable. Sometimes, this means that data is closed, like asset declarations submitted to the government that remain unpublished. Other times this means that data is nonexistent, such as when some political parties or candidates never submitted their financial declarations to begin with, despite legal requirements.

Table 1. The publication gap is often significant

This figure shows the percentage of OGP countries that meet key data metrics for each policy area. The sample includes the 67 OGP countries assessed by the Global Data Barometer.

High-Value Data Gaps

Releasing data by itself is not inherently useful. In the case of data to counter political corruption, the data must be useful for determining whether ethics, the rule of law, and democracy are being protected.

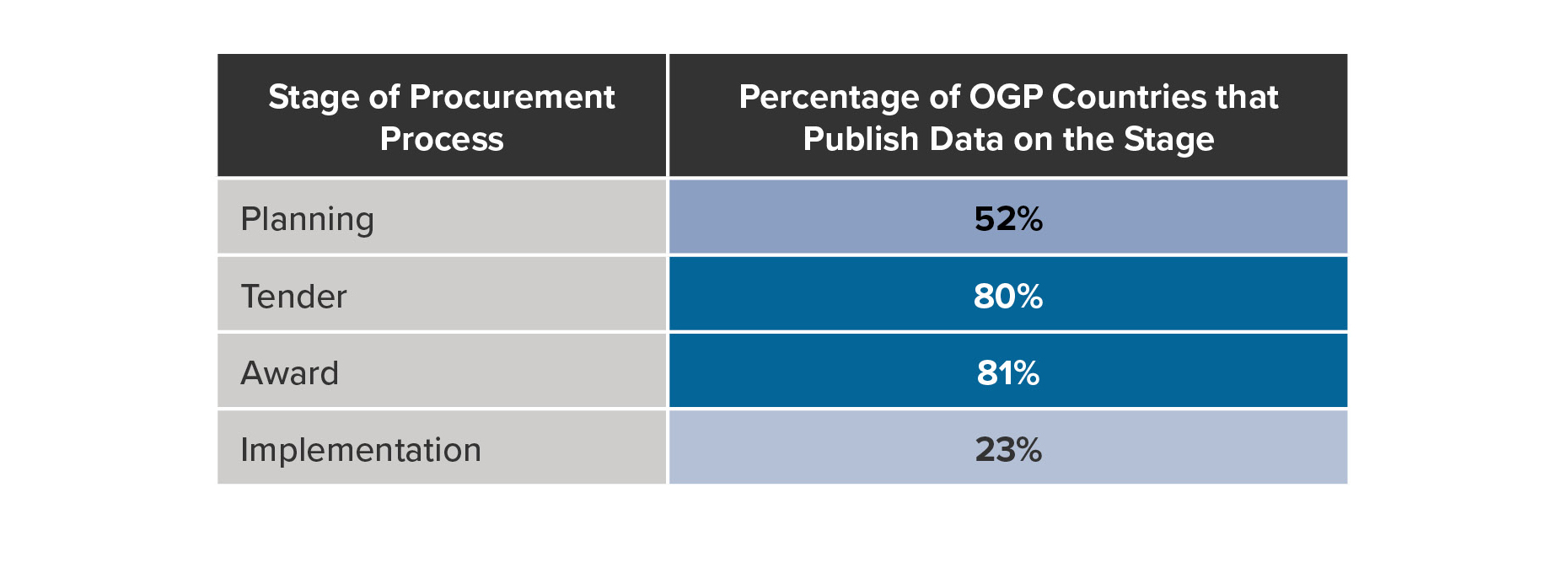

Table 2 shows an example of this gap in the case of open contracting, which is the policy area most widely adopted and implemented among the countries examined in this report. The table examines where data is published. Just over half of OGP countries publish data at planning stages, over three quarters publish tenders and awards as data, but fewer than a quarter publish information on implementation—whether a contract was executed and whether taxpayers got good value for their money. By comparison, the other policy areas have far worse gaps. As a result, even in this relatively strong area of procurement, one can see that OGP countries often have significant room for improvement.

Table 2. Coverage of procurement stages, as an example of high-value data gaps

This figure shows the percentage of OGP countries that publish data on each stage of the procurement process. The sample includes only the 64 OGP countries that publish public procurement data online.

Note: For this analysis, countries with “partial” disclosure are considered cases of “no” disclosure. See the About Broken Links section for details.

Usability Gaps

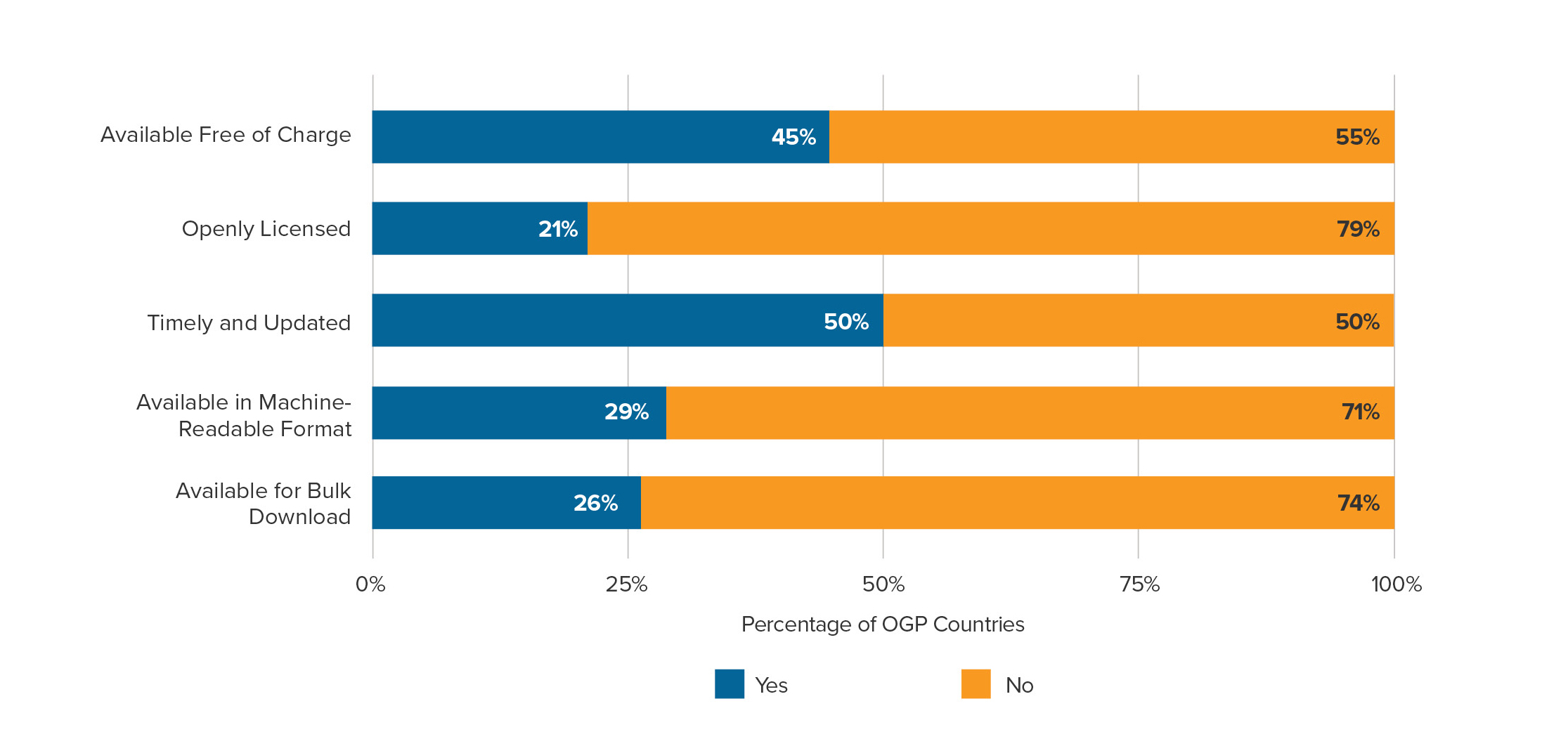

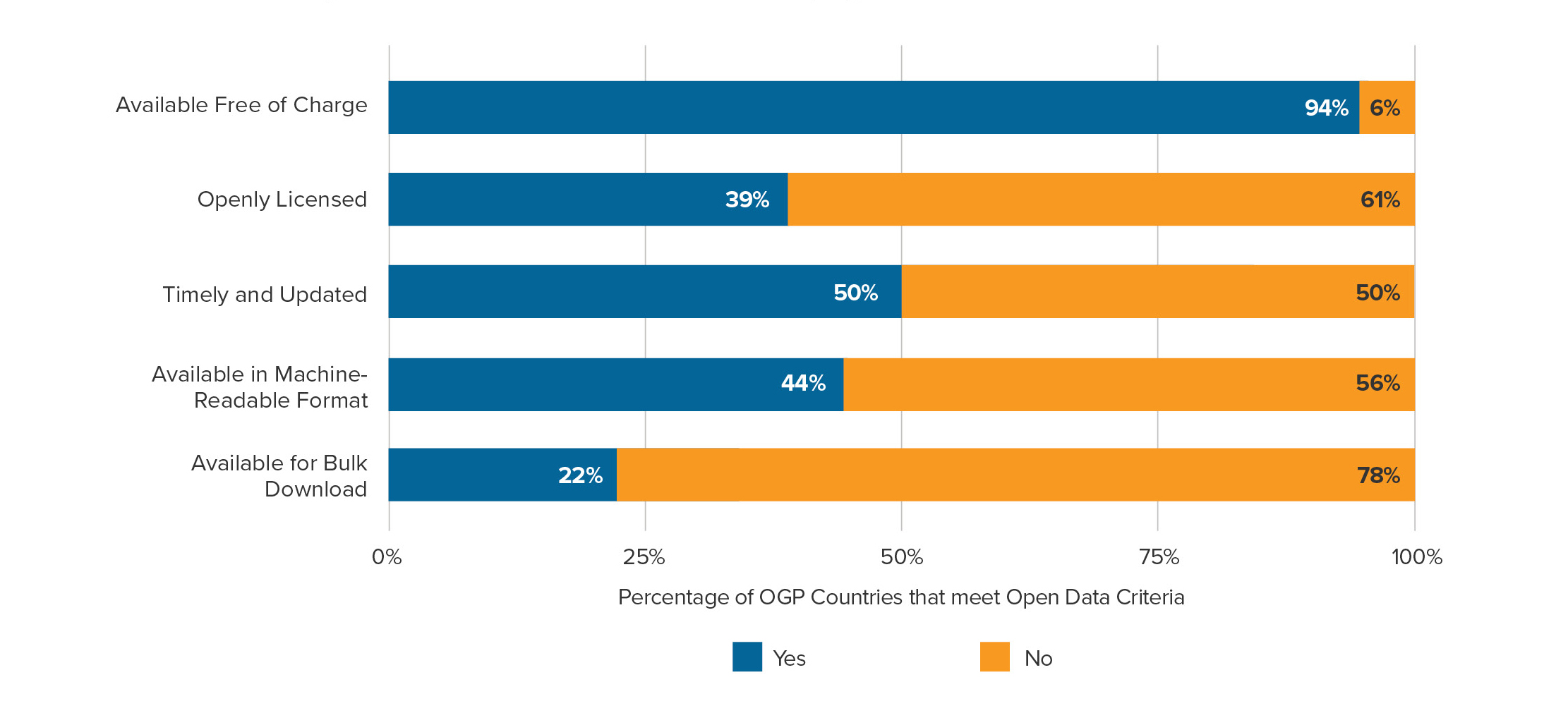

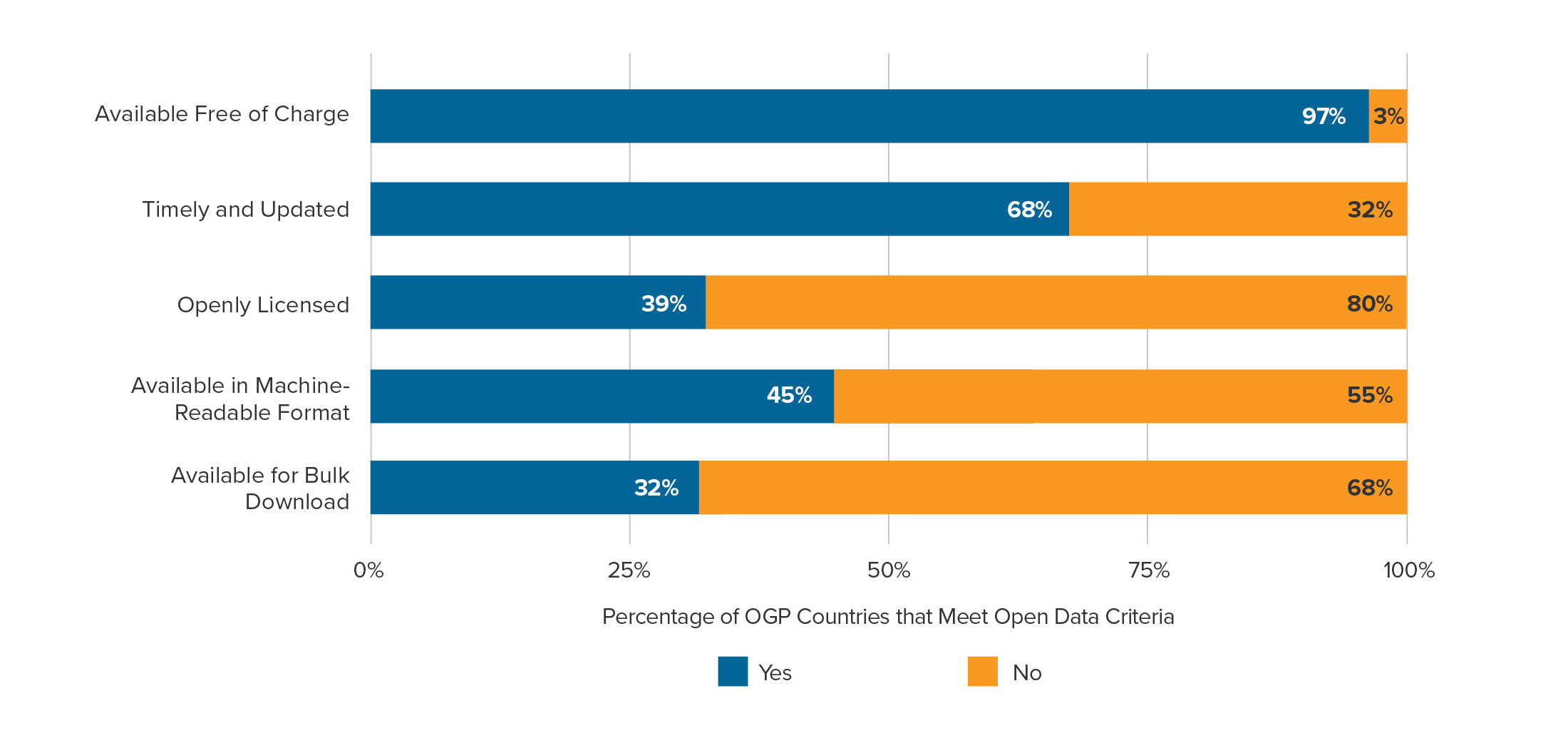

Many gaps with usability across OGP countries make it more difficult—or often impossible—to process data for accountability and oversight. Researchers from the Data for Development Network contributing to the GDB assessed datasets in each policy area on a number of criteria for open data. The specific problems are as follows (with the “typical” case in Table 3):

- Available online: It is not enough that data be available in a government library or document repository; that data needs to be freely available online. Most of the datasets looked for were available online. In the typical OGP country, however, online registers of company beneficial ownership and lobbying registers were unavailable (and not required by law in most countries). Right to information performance data was required in most countries but is not available online.

- Freely available: In some countries, there are high fees for use of data, it is managed by third parties that charge high fees, or it is available on request only. In the typical OGP country, where data is available online, it is also available for free. (Nonetheless, lobbying, company beneficial ownership, and RTI performance are typically unavailable regardless of cost.) While cost may be a barrier in some countries, this is not a typical barrier.

- Timely and updated: Anti-corruption data needs to be available as soon as possible for accountability purposes. According to GDB data, in the typical OGP country, data is consistently and typically too old to be useful for assessing compliance with laws in the short term.

- Open licensed: Data needs to be freely reusable, whether for accountability purposes or for other uses, including commercial uses. According to findings, licenses are unclear or not explicitly open for most datasets in the typical OGP country.

- Machine-readability: For accountability and oversight to occur, data needs to be available in structured formats that allow for data reuse, not simply in scanned documents. In most cases, data, while publicly available, is locked inside non-machine readable formats, making it difficult to analyze.

- Bulk downloadable: Data needs to be available in bulk downloads. As an example, it is simply not practical for watchdog organizations or political parties to monitor asset declarations if a single, separate form is turned in by each parliamentarian. Unfortunately, in the typical OGP country, data must be gathered from multiple pages and sources, even when publicly available, raising the cost of use.

Table 3. Usability gaps among published datasets

This table shows the percentage of OGP countries whose datasets meet open data standards by policy area. Only OGP countries that publish data online are included.

Use Gaps

A final gap, which is not reflected as much in the data, but in the case studies collected by GDB researchers, is that capacity to use the data, in many cases, is lacking. One telltale sign is that investigators in only five of the countries surveyed (of 68) documented notable uses of anti-corruption data by watchdogs. This is likely an underreporting of use cases, since it is entirely reasonable that researchers did not catch all examples of use in a country. Nonetheless, the low number of documented examples suggests that this does not yet show overwhelming use of the data by the public. It will be fruitful for future studies to identify whether user capacity, the relative newness of the data in many countries, the technical nature of some datasets, or lack of available and useful data is the binding constraint for each policy area.

Closing the Gaps: How to Use This Report

This report is a collection of resources built out of the treasure trove of the GDB and the vast experience of reforms in the OGP space. This report is not intended to document all of the shortcomings of OGP members. Rather, a report like this can serve as a benchmark and paint a path forward for OGP members to achieve their priorities.

The resources in this report are meant to help the reformer working at the national, regional, and global levels. The sections are built in a way that they can stand alone. More powerfully, they can be recombined with one another or other resources, depending on the particular political moment or phase of an OGP action plan. The sections of this report are:

- Global findings: This chapter (see Global Findings) and the Executive Summary show the major gaps across the policies and practices surveyed for this report.

- Policy area findings: Each policy area covers the current status of data publication and use around that policy area. There are eight policy areas in this report, along with interoperability, which covers how to link up the different elements of anti-corruption data. Each policy area includes value propositions for the policies, findings from the data, lessons from reformers, maturity models for open data strengthening and use, as well as international standards and guidance.

- Regional findings: These summarize the status of open data across policy areas in each of the four official OGP regions: Africa and the Middle East, Americas, Asia and the Pacific, and Europe.

- Data Explorer (including country findings): Each OGP member that has been part of the GDB survey will also have a country analysis. Over time, the OGP Support Unit hopes to integrate this data within the larger member page on the organizational website opengovpartnership.org to allow for dynamic and continuous updating of the member page.

- About the report: For those wishing to take a deeper dive into the data beyond the short descriptions in the general sections, About Broken Links describes the researchers, the method, and the quality control behind each of the key data points.

A Closer Look At Policy Area Findings

The policy areas featured in this report aim to illuminate the issues surrounding proper implementation of each of the eight policy areas, as well as a focus on interoperability. Each policy area can be used as standalone documents, in combination with one another, with the regional and country analysis, or as part of a larger, omnibus report. Each policy area analysis aims to empower the motivated reformer with the following resources:

- It lays out value propositions to show the strongest, evidence-based arguments for a particular policy.

- It summarizes data from the GDB (and beyond, in a few cases), helping paint a picture of where typical and innovative countries lie. This data includes reviews of law and policy, data usability, and inclusion of high-value elements. The particular high-value elements are unique for each policy area. For example, asset disclosure requires different data points than land ownership disclosure.

- Lessons from reformers highlight stories of success, innovation, and evolution in OGP countries and beyond. These stories are, ideally, inspiring enough to help reformers understand the benefits and approaches of early adopters.

- Maturity models lay out a menu of options for each country to improve its systems, from establishing a minimal policy framework to building complex systems for strengthening each policy area.

- Standards and guidance refer reformers to useful guidance outside of OGP. This includes existing international law, standard-setting organizations, multilateral processes, and policy-relevant applied research.

- Each policy area also includes a section called Beyond Open Data, a collection of ideas from reformers on how to bridge the gap between transparency and real change in accountability and public participation.

Each of these sections is a cornucopia of resources, ideally thorough and fact-based enough to give the curious reformer the tools they need to move their reforms forward while at the same time brief enough to be useful.

Conclusion

Ideally, the gaps documented in this report can be addressed through OGP action plans, which are a useful way to advance domestic implementation, especially within each policy area. Working with civil society, governments create action plans that include concrete commitments to improve transparency, civic participation, and public accountability. At the end of each action plan cycle, OGP’s Independent Reporting Mechanism (IRM) evaluates the results.

Many OGP members have already used their action plans to address corruption through data and more. Members have made more than 300 commitments related to right to information frameworks, as well as more than 60 commitments related to asset declarations. Lobbying reforms have been less common, with only about 25 relevant commitments, but IRM evaluations show that these commitments have achieved above-average early results. This suggests that OGP action plans are an important vehicle for change.

The contributors of this report hope that it is a useful resource for looking to fuse the fight for democracy with the fight against corruption. In the process, they will strengthen both.

About Broken Links

Background

Broken Links: Open Data to Advance Accountability and Combat Corruption synthesizes the new global survey data released by the Global Data Barometer (GDB)—in collaboration with regional and policy-focused partners, including OGP—into a series of research products. These products analyze the current state of data to combat political corruption, showcase examples of promising reforms, and provide recommendations on how OGP members can use their action plans to close existing gaps. This section explores the research goals, structure, and scope.

Goals and Approach

The report builds on the first OGP Global Report, published in 2019. Similar to that research, this report provides thought leadership to the Partnership, assesses the state of play of open data in several key policy areas, and provides comparative snapshots of all OGP members. Specifically, the goals of this report include:

- Agenda setting: Raise the agenda for strengthening democracy, limiting corruption, and enhancing citizen voice through reforms in OGP at the global and national levels.

- Close the gaps: Create compelling incentives to close the ambition and implementation gaps at the national level.

- Comparability: Provide a means by which countries may compare themselves with one another.

- Collective action: Cultivate a sense of shared ownership and accountability for cross-cutting reforms in priority areas for all OGP countries.

- Context and achievement: Demonstrate and highlight many of the most relevant, ambitious, and high-impact commitments.

Report Findings

To achieve the goals above, the report contains four complementary—yet standalone—sections:

- Global findings: These findings review the state of data to counter political corruption across all OGP countries, highlighting the major gaps that exist across the policies and practices surveyed for this report.

- Policy area findings: Eight policy areas (plus one on interoperability across policy areas) include value propositions for policies, findings from the data, lessons from reformers, maturity models for better open data, and international standards and guidance.

- Regional findings: Four regional summaries (Africa and the Middle East, Americas, Asia and the Pacific, and Europe) describe the state of play of data to counter political corruption and highlight regional innovators, with a focus on three featured policy areas.

- Data Explorer (including country findings): An online tool visualizes the progress and areas for improvement based on the data for each OGP country reviewed by the GDB (see About the Data section for details).

Together, these findings are meant to inspire new, ambitious OGP commitments by identifying areas for growth and examples of innovations at the global, regional, and country levels. The method used to construct each section is described in the About the Data section.

Scope of the Report

This report focuses on nine areas that are directly relevant to countering corruption covered by the GDB. These areas are all foundational to promoting transparency in the interests influencing official decisions, providing a deterrent to potential abuses of public office, and greater accountability through the ballot box, the courts, or other means. They were selected because they are:

- OGP priorities, as recognized in strategic and work planning documents

- Cornerstones of open government, as identified in OGP founding documents

- Initiatives of recent OGP Steering Committee Co-Chairs

- Areas of ongoing collaboration with partner organizations

- Amenable to an analysis through the lens of open data

The nine policy areas included in this report are:

- Asset Disclosure

- Political Finance

- Company Beneficial Ownership

- Land Ownership and Tenure

- Public Procurement

- Lobbying

- Right to Information Performance

- Rulemaking

- Interoperability

See the section of the report titled A Data-Focused Approach for details on the specific data covered within each policy area. For details about the specific indicators that fall under each policy area and how they were used in the various modules of this report, see the About the Data section.

Review Process

Each policy area chapter underwent a review phase in the first half of 2022. During this process, respected policy experts from partner organizations—in addition to OGP staff members—reviewed the draft documents and provided both written and verbal feedback. These experts are listed in the Acknowledgments section of the report. The full draft report was also shared with the GDB team for their input and suggestions.

About the Data

This report includes data from two main sources: (1) the GDB primary survey data and (2) the OGP action plan data, including assessments from OGP’s Independent Reporting Mechanism (IRM). Each report section analyzes and visualizes these data sources in slightly different ways. This section lays out the characteristics of each data source and describes the approaches used for each section of the report. (This section focuses only on the GDB data elements actually used in this report. See Good to Know: GDB and OGP terminology compared for an explanation of terms and how they differ between this report and the Global Data Barometer report.) See the full GDB methodology in the GDB Global Report for additional information.

About the GDB Data

Collection

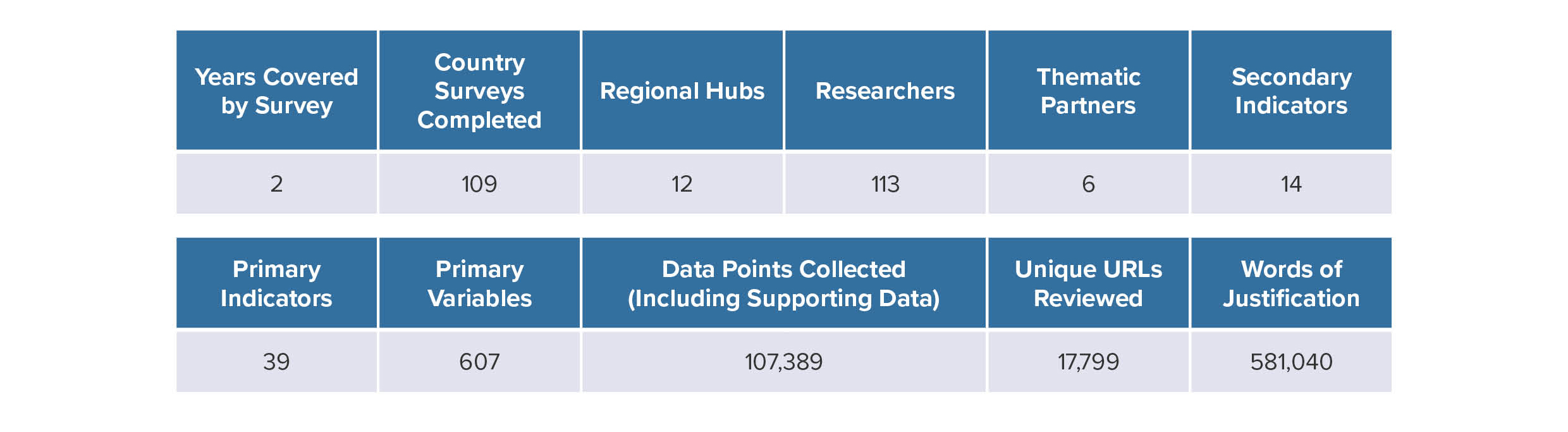

The GDB team partnered with a network of regional hubs to collect the data.[9] With the GDB team’s support, the regional hubs recruited and trained experts, mostly in-country researchers, who collected the primary data in 109 countries between May 2021 and late 2021 (See Table 4. GDB data collection at a glance). During this process, the researchers for each country completed an in-depth survey using the GDB Handbook (see the next subsection for details on the data structure). The researchers assessed only information between May 1, 2019, and May 1, 2021. Any developments that took place after May 1, 2021, will be reflected in a future edition of the GDB.

Table 4. GDB data collection at a glance

For many survey responses, researchers provided a written justification and supporting evidence. This includes information such as the URLs to specific laws, policies, or datasets; the latest update date of a dataset; or the file format in which data is available. All supporting evidence (together with the full set of response values) is publicly available online.

To complement the responses collected in this primary survey, the GDB team also conducted a short government survey in parallel. Governments were invited to provide evidence that a researcher might not be able to find through desk research or interviews. Twenty percent of governments contributed to this first edition government survey, which was a shorter version of the expert survey.

In addition to the 39 primary indicators, pillar and module scores also draw upon 14 secondary indicators. These were taken from carefully reviewed external sources and each transformed onto a 0–100 scale, with missing values imputed where appropriate.[10] These secondary indicators are not used in this report.

After the collection phase concluded, the survey responses were reviewed by regional hubs, other national researchers, thematic partner organizations (including OGP[11]), and the core GDB team. The first phase of review was led by researchers and regional hub coordinators, with input from the core GDB team. This consisted of a full review of the expert survey responses, along with their evidence and justifications. The second phase of review focused on data validation. During this phase, the core GDB team conducted validation checks, cross-checks with other countries and sources, and reviews of outliers, drawing on feedback provided by country researchers and thematic partners. The government-provided evidence was also taken into account during this phase.

Structure

The GDB is a multi-dimensional index that comprises (in increasing level of specificity): pillars, modules, indicators, and sub-questions. At its broadest, the data covers four key pillars (see Table 5. The four GDB pillars). This report deals mostly with the Governance and Availability pillars. The Governance pillar focuses on the laws and policies that govern data collection and publication; the Availability pillar focuses on the existence of data and its adherence to open data standards.

Table 5. The four GDB pillars

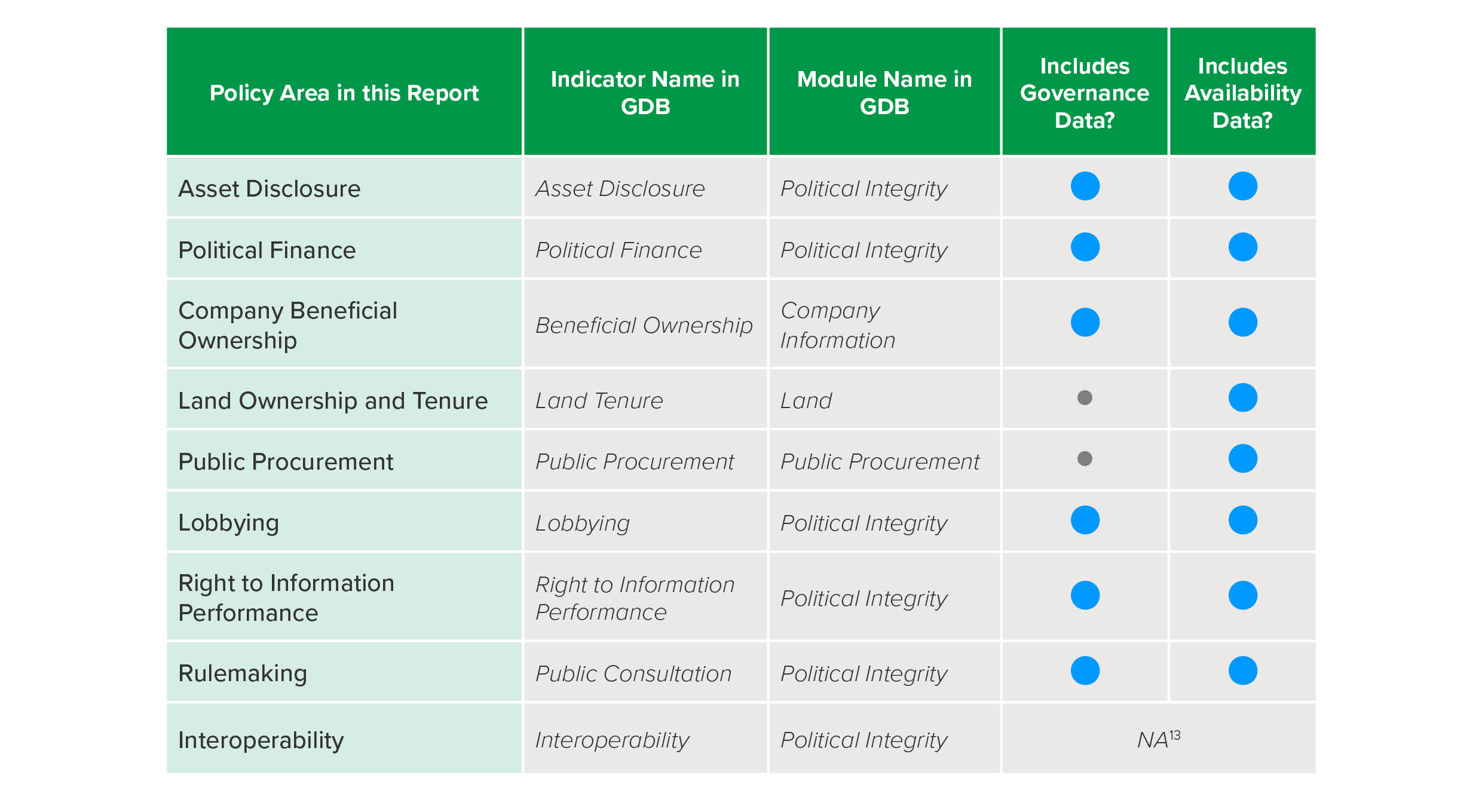

The study is also organized into core and thematic modules. Core modules (Governance and Capabilities) focus on the overarching country context (e.g., data protection, data sharing frameworks), whereas thematic modules explore specific domains, such as political integrity, public finance, and climate action. Most—but not all—of the policy areas covered by this report can be found in the “Political Integrity” thematic module of the GDB (see Table 6 for a list of each policy area covered in this report and its corresponding GDB sections).

Table 6. Mapping of policy areas in this report

Not all GDB indicators include questions about laws and policies governing anti-corruption data (referred to as Governance in the GDB). Specifically, as shown in the table above, the land ownership and tenure, public procurement, and interoperability sections lack these questions. The specific GDB questions used for each of the indicators are presented in the Annex.

Limitations

The GDB data has some limitations that are worth noting:

- Lack of global country coverage: The GDB covers an impressive 109 countries in its first edition, but this, unfortunately, does not include all OGP countries. Specifically, the GDB assesses 67 of the 77 OGP participating countries. The remaining ten countries were not assessed due to difficulties in finding in-country researchers.[13] In future editions, the OGP Support Unit and GDB team hope to expand data collection to cover all OGP countries. If you or your organization are interested in participating in the data collection for these countries, please contact [email protected].

- Inconsistency of robustness across survey questions: The robustness and comparability of specific survey questions are stronger than others. Despite multiple rounds of reviews (see the Collection subsection above), type I and II errors may still remain in the data. As a result, if users spot some data they do not consider complete or accurate, please contact the GDB team at [email protected] or the OGP team at [email protected].

- Limited data on specific topics: Some topics are underexplored in the first edition of the GDB. For example, only a small number of indicators look at the use and impact of data due to the complexities of measuring use consistently across countries. Likewise, the survey offers few opportunities to document the role of inclusion broadly and gender equality specifically, such as whether data initiatives are gender-balanced or have significant gendered impacts. The survey is expected to expand the coverage of inclusion-related indicators in future editions. Finally, as mentioned above, data on the quality of legal frameworks was not collected for a few policy areas.

GOOD TO KNOW GDB and OGP Terminology Compared Many terms in this report were modified from how they appear in the GDB for brevity, precision, and ease of understanding. (In addition, as noted, this report builds on the GDB “Political Integrity” module to include “Company Beneficial Ownership,” “Public Procurement,” and “Land Ownership and Tenure” to match the scope of OGP’s strategic direction.) For readers more familiar with GDB terminology or those looking to identify the exact source of this report’s data in the GDB dataset, below are the most commonly used terms and the differences between reports.

|

About the OGP Data

Collection

OGP members advance a variety of policy areas through the co-creation and implementation of two- or four-year action plans. After each action plan is submitted, the OGP Support Unit tags every commitment for its relevant policy areas and sectors. The current list of policy area and sector tags can be found in the OGP Commitment Database under “Definitions”.

OGP’s Independent Reporting Mechanism (IRM) evaluates every national action plan after submission and after the end of the implementation period.[14] The IRM’s Action Plan Review—which replaced its Design Report in 2020—reviews each commitment after the action plan’s submission for verifiability, relevance to open government values, and potential for results. Following the end of the action plan’s two- or four-year implementation period, the IRM evaluates the completion and early results of commitments in the Results Report.

Structure

The Support Unit has collected structured data on all OGP commitments submitted since 2011, including their relevant policy area and sector tags and IRM assessments, in a database. The database is published on OGP’s Open Data webpage in multiple formats under a Creative Commons (CC BY 4.0) license. The data is updated daily.

Limitations

The OGP data presents several limitations, namely:

- Time lag of assessments: IRM Action Plan Reviews are published within four months of action plan submission. IRM Results Reports are published after the conclusion of the action plan period. This means that the latest data on commitment implementation and early results (which are derived from the latter) in this report comes from OGP action plans submitted in 2019 or earlier.

- OGP commitments as a standard unit of analysis: OGP commitments vary widely in their range of activities. This makes comparisons difficult, even within the same country or focus area. For instance, the policy areas group together OGP commitments based on their focus area to derive average rates of ambition, implementation, and early results. However, these commitments are very different from one another, ranging from commitments that aim to update a web page to those that propose passing new legislation. Nonetheless, given the large amount of information we collect about them, OGP commitments remain the best—albeit imperfect—unit of analysis for OGP research.

- Changes in IRM method over time: The method used to assess some of the IRM key metrics has changed over time. For example, the IRM now assesses commitment ambition using an indicator called “Potential for Results” rather than the “Potential Impact” indicator used previously.[15] In cases such as these, the authors of this report have combined several indicators to produce longitudinal data. See the method section of the OGP Vital Signs report for a more detailed discussion of OGP variables.

How Data Is Used in the Report

The GDB data is analyzed differently in each section of this report. However, some methods are applied consistently throughout the report. These are presented below. The rest of this section then describes methods that are specific to each section.

- Raw scores instead of calculated scores. This report does not use any of the calculated scores in the GDB, which rely on different multipliers and weights by question.[16] Instead, the analysis only uses raw response values, such as “no,” “partial,” and “yes” for most GDB questions. This helps to ensure that the results are actionable for policy makers, as each score is interpretable and has a clear action implication.

- Simple fractions as a method of aggregation. References to percentages of OGP countries meeting a certain threshold according to GDB data, such as making data available or requiring data publication, are calculated using simple fractions (e.g., the number of OGP countries that make data available out of the total number of OGP countries assessed by the GDB). Similarly, discussion of OGP commitment performance refers to simple fractions (e.g., the number of ambitious lobbying commitments out of the total number of lobbying commitments assessed for ambition). Given the generally low number of commitments across the board, country weights are not included.

- Online and government-published requirements for data availability. References to the percentage of OGP countries with data available on different topics are common throughout this report. In each case, data availability is defined as any data that is online and “available from government, or because of government actions.” This excludes data published by nongovernment entities, such as civil society groups. This also means that OGP countries are only considered to publish “high-value” information if that information is available online; it is not sufficient for the information to be available upon request or accessible through freedom of information requests (see the Executive Summary subsection for more information on “high-value” elements).[17] Note that the threshold for having data available is publishing any data online. In many areas, like land ownership and tenure, this minimum level of data may not actually be useful for monitoring purposes. Other aspects of GDB assessments (like “high-value” elements and usability) are therefore important complements.

- Operational and binding requirements for legal mandates. Legal requirements are discussed throughout the report, specifically whether legal frameworks exist that require data collection and/or publication. In these cases, only laws, policies, or regulations that “exist and are operational” are considered; draft laws or laws that have yet to be implemented are excluded. Regarding legal requirements for data publication, only requirements “set out in binding policy, regulations, or law” are considered. Additionally, these requirements must be part of an operational legal framework; draft laws that require data publication are not considered for the purposes of this report.

- Treatment of partial data. For most GDB questions about whether a country requires publishing or publishes data, researchers can respond in three ways: “no,” “partial,” or “yes.” Unless otherwise specified,[18] for ease of presentation, “partial” scores are considered to be cases of “no” availability or requirement.[19] For example, according to research conducted for the GDB, Ireland is considered to partially publish unique identifiers for each lobbyist and public official. As a result, in the lobbying section, Ireland is not considered to fall in the seven percent of OGP countries that publish these unique identifiers.